By Liam Denning

Americans are reminded about high gasoline prices daily, every time they drive. Another energy cost comes to their attention monthly: utility bills. These are now also rising, creating an added problem for households, for the president — and, as it happens, for utilities.

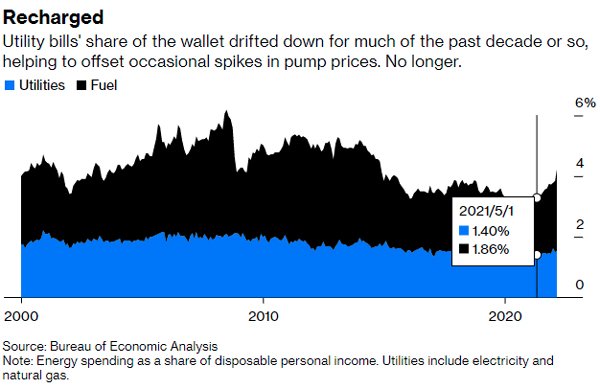

Governor Ron DeSantis of Florida recently threw a curveball when he vetoed utility-friendly solar power legislation (see this). Whatever his political calculations, his stated rationale of protecting inflation-addled voters from rising utility bills will resonate. Energy’s share of disposable personal income hit its lowest point ever in April 2020 at just 2.1%, 1 as Covid-19 swept through. By March of this year, that share had doubled to its highest level since 2014.

Rebounding gasoline prices were mostly to blame. But over the past year, the bite taken by electricity and gas bills has begun to expand, too.

This arrests a downward drift in the share of spending taken by power and gas over the past decade or so, a useful offset during bursts of high oil prices. Although the overall burden remains well below that of previous energy crises in 2008 and the 1970s, the current increase is notable for its speed and its impact across both fuel and utility bills.

The latter break down into two broad components. One involves utility companies’ simply passing along to consumers the cost of sourcing energy, whether it be the fuel to run power plants and fill gas pipes or the cost of buying power from independent generators. The utility doesn’t make its money on this; it’s just a middle man. The other component consists of costs that utilities agree on periodically with regulators, primarily non-fuel operating costs and investments made in the grid and associated infrastructure, including a regulated return on equity.

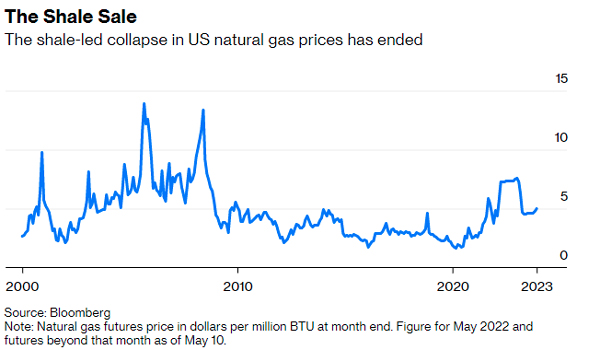

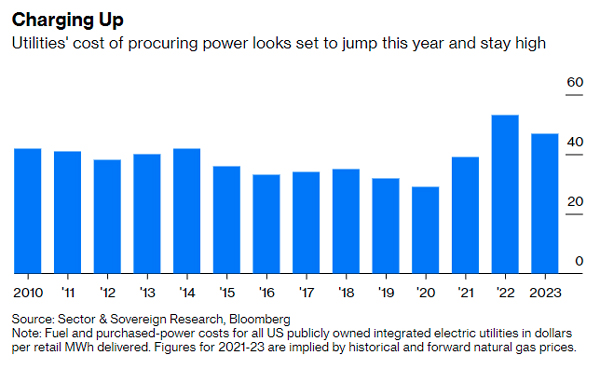

On all fronts, the 2010s were halcyon years. The shale boom suppressed the price of natural gas and, by extension, of producing electricity, since gas-fired plants set the wholesale power price in much of the US. With those pass-through costs flat or declining, regulators could allow utilities to invest heavily in the grid while still keeping bills in check. Even as the asset base of publicly traded utilities expanded by more than 7% a year from 2015 to 2020, average residential bills remained pretty flat, according to Hugh Wynne, an analyst with Sector & Sovereign Research.

Now it’s safe to say that shale dividend has run its course.

Based on correlations observed during the 2010s, every $1 move in benchmark natural gas prices implies roughly a $5 per megawatt-hour move in utilities’ fuel and power-purchasing costs, Wynne calculates. Having averaged $2 and change in 2020 and about $3.70 in 2021, gas futures today imply $6.50 for this year and $5.25 in 2023. So utility costs look set to hit levels far above what we’ve become accustomed to over the past decade.

All else equal, these figures would imply that utility bills will be 23% higher in 2022 than they were in 2020, the last year for which complete data are available, and 10% higher than the implied figure for 2021. 2 In practice, utilities’ own hedging strategies may ameliorate some of the impact, and regulators may spread the rate increase over several years. Still, those costs will feed through somehow, and it will mark a big change from the pre-pandemic years. Even before the energy shock, bills were due to rise — thanks to continued heavy investment by utilities and a lack of room for gas prices to fall further. And broader inflation, raising the price of everything from steel to labor, adds further pressure.

Most businesses welcome the chance to charge their customers more. But utilities, being regulated monopolies, are not most businesses. Inflation presents them with several difficulties.

Whereas an ordinary business can raise prices immediately to deal with higher input costs, utilities face constraints. They can pass through higher fuel and power costs, of course, although even this presents some difficulty. Recall that falling fuel and power costs allowed regulators some room to approve higher investment spending during the 2010s. But inflation complicates those approvals going forward, especially as regulators are usually appointed by state politicians or directly elected.

More pernicious is the fact that, pass-through costs aside, utility economics don’t really account for inflation, not in real time anyway. Utilities earn a return on the book value of their regulated assets, so inflation erodes their real earning potential. Moreover, adjusting bills to take account of rising inflation requires regulatory approval, which can take many months, causing a lag.

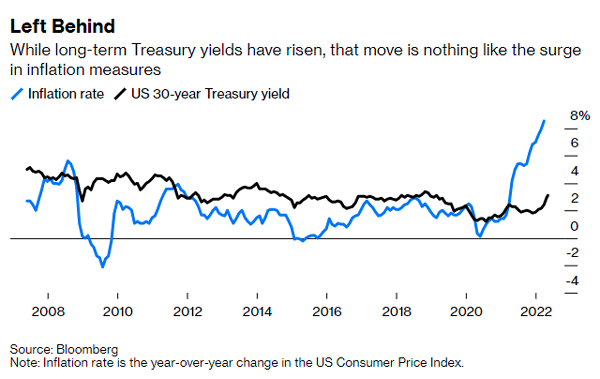

In addition, Wynne points out that when utility regulators factor inflation into setting the return on equity, their expectations tend to be anchored in trailing inflation rates and how these have fed into Treasury yields. In methodological (and political) terms, regulators skew team transitory, and that approach tends to underplay the impact of a sudden jump in inflation such as we are experiencing today

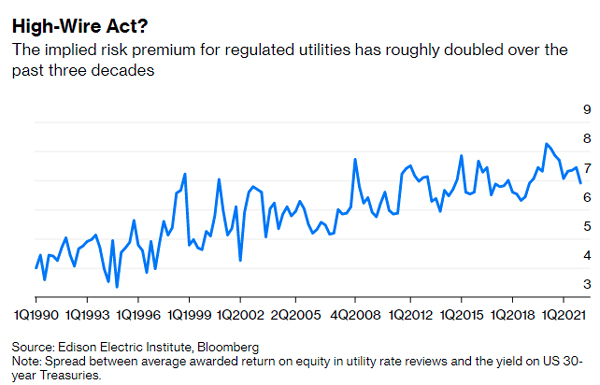

A wild card here is whether the reappearance of inflation will lead to a broader rethink of what utilities’ fair rate of return should be. Over the past 30 years or so, the spread between the average regulated return on equity and the 30-year Treasury yield has roughly doubled to 8 percentage points. Think of this as another boon to the industry from that long disinflationary period. Taking it as a proxy for the industry’s risk premium, one has to ask: Did the utility business really get that much wilder and crazier over the years? Hardly, outside of some special cases such as California’s Pacific Gas and Electric Co.

That spread has shrunk a little since early 2020. But as regulators balance the investment needs of a transforming grid with the pressure placed on households by inflation, the spread — utilities’ return on investment — might yet take more of the strain.

Recent volatility in stocks, with heavy selling of high-flying technology companies in particular, has pushed utilities back to a 20% premium to the S&P 500, last seen just before the pandemic took hold. 3 Investors tend to seek safe havens in a storm, of course. The wrinkle is that, with this particular storm encompassing a sudden shift in the trajectory of inflation and yields, utilities may not be quite as rock solid as believed.

____________________________________________________________________

Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy, mining and commodities. He previously was editor of the Wall Street Journal’s Heard on the Street column and wrote for the Financial Times’ Lex column. He was also an investment banker. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg on May 11 , 2022. EnergiesNet.com reproduces this article in the interest of our readers. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of socially, environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

EnergiesNet.com 05 12 2022