Sylvia Westall, Grant Smith, and Anthony Di Paola, Bloomberg News

DUBAI/LONDON

EnergiesNet.com 06 09 2022

When campaigning for president, Joe Biden vowed to turn Saudi Arabia into a “pariah” over the brutal killing of a newspaper columnist. Once in the White House, he temporarily froze weapons sales to the kingdom over its war in Yemen. He also outlined a vision to make the US a renewable energy powerhouse, less reliant on an oil market where the Saudis hold so much sway.

But with Russia’s invasion of Ukraine posing the biggest disruption to energy supplies in decades, Biden is having to take a different tack, recalibrating an alliance that is increasingly critical to the global economy—and the most strained it has been in years.

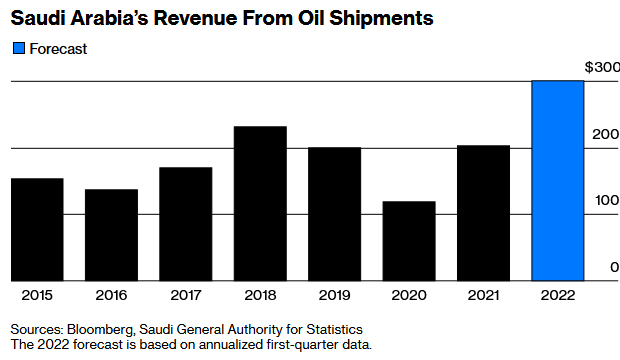

With the oil market in turmoil, the world’s biggest exporter of crude once again has the leverage to make demands. It is raking in $1 billion a day from oil, and Saudi Arabia’s economy, alongside India’s, is predicted to grow the fastest of any G-20 nation.

A glimmer of reconciliation came on June 2 when OPEC+, a group of major oil producers effectively led by the Saudis, agreed to accelerate output increases after months of rebuffing US entreaties. The unexpected move is an important first step in a global push to target Russian exports with sanctions. Biden is contemplating a visit to the kingdom in coming weeks as part of a wider trip to the Middle East.

“Both sides wanted to see relations stabilized,” says Bob McNally, president of Washington-based consultant Rapidan Energy Group and a former White House official. “The president has rediscovered the importance of stable oil and gas prices—and specifically the critical role played by Saudi Arabia.”

What Biden is finding, though, is a Saudi leadership that wants to assert its own agenda. Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman wants public recognition from Biden as de facto ruler after the president shunned him over the murder of the Washington Post’s Jamal Khashoggi. He also wants American investment and easier access to US military hardware.

Also critical are stronger guarantees the US will defend the kingdom—now most notably from attack by Iran and its proxies—as part of a pledge that’s been the cornerstone of the Saudi-oil-for-American-security pact dating back to 1945. The Saudis, along with the neighboring United Arab Emirates, want written agreements, according to two people familiar with the discussions in Riyadh and Abu Dhabi. The US guarantee has never been formal and isn’t considered as trustworthy as in previous decades, says one of the people, who asked not to be identified because the conversations aren’t public.

Saudi officials have also found it tougher to make their case to congressional Democrats than in the past, three people familiar with the discussions say, and a Biden visit could help turn the page. “Sometimes the US takes these countries for granted,” says Ebtesam Al-Ketbi, who runs the Emirates Policy Center think tank in Abu Dhabi. “If there’s a commitment on the security side, that would go a long way.”

Biden needs an ally that can help restore order to the oil market. The price of a barrel of crude has surged more than 50% this year to around $120 and could even test $200 as European Union sanctions squeeze Russia’s exports, according to a Bloomberg Intelligence analysis. US gasoline prices have already hit a record, and the holiday driving season has only begun. Rampant inflation has become a source of political peril for a president facing midterm elections with approval ratings sagging toward 40%.

Unlike the leaders of Saudi Arabia, Biden has no direct control over how much oil flows out of American wells. That’s largely up to the hundreds of shale drillers in West Texas, and their shareholders have long grown weary of the industry’s pre-pandemic grow-at-any-cost model.

“The Saudis are coming at a reset from a position of strength,” says Karen Young, a senior fellow at the Washington-based Middle East Institute. “They feel vindicated over their stance on oil.”

Indeed, the White House has much more to do before Saudi Arabia and the UAE agree to turn on taps enough to help lower prices at the pump, according to the people familiar with the discussions. The OPEC+ move this month barely moved the needle, even if it did require Riyadh to gently pivot away from Russia, with which it has jointly managed global crude markets for the past five years.

Analysts at JPMorgan Chase & Co. project that barely a quarter of the 648,000-barrel-a-day addition scheduled for July and August will make it to the market because many OPEC members aren’t in a position to reach those levels. It also doesn’t address an arguably bigger problem: a shortage of refining capacity to process the oil into gasoline and jet fuel. “It really doesn’t do anything to change the fundamental picture,” says Jeff Currie, head of commodities research at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. “This market is going to get significantly tighter as we head out toward the summer months.”

Underlining the urgency, Biden has dispatched his Middle East envoy, Brett McGurk, and senior adviser for energy security, Amos Hochstein, on multiple trips to Saudi Arabia and the UAE since late last year. Recently they discussed ensuring stable global oil supplies, rather than simply asking for oil. As for the president going, he will hold any meeting that serves the interests of the US, Press Secretary Karine Jean-Pierre said on June 7. “He believes engagement with Saudi leaders clearly meets that test, as has every president before him,” she said.

To many observers, it looked as if the partnership forged 77 years ago at Great Bitter Lake in the Suez Canal between Franklin Roosevelt and King Abdulaziz, Saudi Arabia’s founder, was in terminal decline. The relationship has frayed before. Saudi Arabia opposed the creation of Israel in 1948 and cut oil supplies to the US during the 1973 Arab embargo, causing prices and inflation to spike. The alliance was tested after the Sept. 11, 2001, attacks at the hands of mainly Saudi terrorists. Still, McNally, the former White House official, says it has reached a low point under Biden.

Thus far, Biden has dealt only with 86-year-old King Salman, declining to engage with Prince Mohammed. While Saudi officials say the monarch is in good health, the cost of insuring the kingdom’s debt rose to its highest level in a year when he spent a week in the hospital in May.

The mood began to shift as oil prices climbed last summer in tandem with a rebound in fuel demand. After Russian President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine in February and the boycott of Russian shipments propelled crude prices to almost $140 a barrel, Washington stepped up its efforts at a rapprochement with Riyadh.

While Saudi cooperation may aid western efforts to isolate Russia, analysts don’t expect Riyadh to drop Moscow as a partner in managing oil output and prices anytime soon. The OPEC+ alliance has proven too useful to both nations, most notably during the 2020 pandemic, for it to be easily abandoned. Putin has built a rapport with Prince Mohammed, phoning him several times this year to discuss oil markets and regional security.

“Russia is seen as essential to maintaining the stability in the oil market, and for an oil producer, nothing outside their physical survival is more important,” says McNally. “There’s no way the Saudis are going to kick them to the curb.”

Still, the symbolism of a pivot back toward America’s side—especially with US-China rivalry looming large—may in itself give oil markets some reassurance. If the conflict in Ukraine drags on, the White House may need to ask the Saudis for ever greater volumes to replace Russian crude, further increasing their leverage.

“The frost is melting in Saudi-US diplomatic relations,” says Bill Farren-Price, a director at Enverus Intelligence Research and a veteran observer of the OPEC cartel. “But it will take more progress before full normalization.”

—With Ben Bartenstein, Paul Wallace, Vivian Nereim, Justin Sink, Matthew Martin, and Salma El Wardany

bloomberg.com 06 09 2022