Stephan Kueffner | Bloomberg

LIMA

EnergiesNet.com 12 19 2022

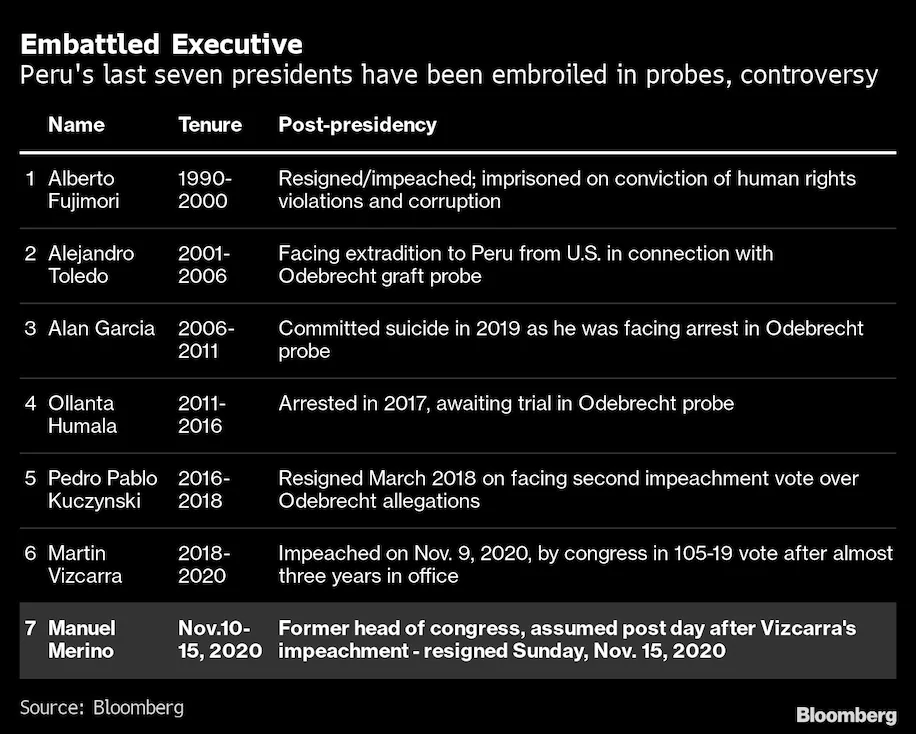

In recent years, Peru has been no stranger to political turmoil. It currently is on its sixth president in seven years — or should still be on its fifth, according to the crowds whose protests led to a declaration of a state of emergency in mid-December. They took to the streets after a day in which President Pedro Castillo declared congress dissolved only to be swiftly impeached by it and jailed after he tried to flee to the Mexican embassy. Now Peru’s conflicts are causing rifts across Latin America as left-wing governments announced support for Castillo while others recognized his successor. Behind the crisis lies a deep urban-rural divide between the elite hub of the capital Lima and impoverished regions, and a fragmented political system in which weak presidents now routinely face impeachment by unruly congresses, jail time for corruption or both.

1. How did we get here?

The politically inexperienced Castillo, who represented a small radical-left party, Peru Libre, narrowly scraped into office in elections in 2021 and never established a firm hold on power in the face of stiff opposition from a congress dominated by conservatives. Many of his problems were self-inflicted: He changed his cabinet members about 80 times in his brief time in office, less than 17 months. He also faced mounting accusations of corruption and several members of his inner circle were forced to resign after prosecutors brought charges against them. The chaos provided congress with multiple reasons to try to unseat him, although two impeachment votes failed before a third effort was prepared early in December.

2. What did Castillo do?

Hours before facing his third impeachment trial on Dec. 7, Castillo ordered Peru’s congress dissolved, the courts restructured, a nightly curfew imposed and said he would rule by decree for nine months before convening an assembly to write a new constitution.

3. Why was he facing impeachment?

In part, the motion to impeach was based on reports of a corruption investigation involving the president. But it was also driven by the complicated mechanics of the Peruvian constitution. Presidents have the power to dissolve congress and force new elections if a congress twice votes against the government in a motion of confidence vote. In late November, Castillo’s prime minister resigned after congress refused to vote on a motion of no confidence. The courts were preparing to rule on Castillo’s claim that the failure to vote should count as a vote of no confidence when he moved to dissolve congress.

4. What happened after Castillo declared congress dissolved?

The police and the military refused to obey Castillo’s decision and most of his cabinet immediately quit, the constitutional court called his announcement a coup, the number of lawmakers backing his impeachment soared and they voted him out office within hours. Castillo was arrested and ordered to stay detained for a week, with a judge subsequently ruling he should remain in custody for another 18 months.

5. Who took over?

Castillo’s vice president, Dina Boluarte, a lawyer also elected on Peru Libre’s ticket, was next in the line of succession and was sworn in the same afternoon to become Peru’s first female president.

6. What happened after that?

Protests broke out in many rural areas, closing roads and airports and leading the government to declare a nationwide state of emergency to clamp down on violence that left at least 20 dead as of Dec. 16. Boluarte promised early elections, as protesters were demanding, but congress rejected the measure. Castillo’s term ends in 2026.

7. What do Castillo’s supporters say?

Poor rural Peruvians angry over inflation and the removal of a president whose modest rural background they identify with want him reinstated and elections held for a new constitutional assembly. His defense lawyer insists Castillo is innocent of “rising up in arms,” the charge brought against him.

8. How is this dividing Latin America?

Four countries led by left-wing presidents — Argentina, Bolivia, Colombia, and Mexico — have publicly backed Castillo as president, while the conservative-led governments of Ecuador, Costa Rica, and Uruguay, along with left-leaning Chile and the US, recognize the Boluarte administration, dividing a region hit by inflation and a disproportionate number of deaths during the pandemic. Brazil’s President-elect Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva both wished Boluarte luck and regretted Castillo’s ouster.

bloomberg.com 12 17 2022