By Robbie Gramer and Anusha Rathi

In mid-October, Russia, China, and a coalition of other autocratic countries sent a furious letter to a top U.N. diplomat expressing their “shock” at the maneuverings of other countries in the United Nations over a major new piece of international law. An unusual coalition of smaller U.N. powers led by Mexico, Gambia, and Bangladesh found a way to jump-start the process of creating a first-ever U.N. convention on crimes against humanity over the fierce objections of Moscow, Beijing, and their allies—who had stalled the process for three years straight.

But this time, Moscow and Beijing got outfoxed. And they knew it.

With Mexico in the lead, a coalition of countries bucked the normal procedures and traditions of consensus in a key U.N. committee that oversees international law, opening the door for the eventual adoption of the first-ever U.N. treaty addressing crimes against humanity. No such treaty exists currently, something that human rights advocates and legal scholars describe as a gaping hole in international law.

The process for finalizing a draft treaty on preventing crimes against humanity and getting world powers to adopt it is still years off, and the fight is far from over. But as former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill said in a different context, if it’s not the beginning of the end, then it’s the end of the beginning. This story is based on internal U.N. documents and interviews with nine U.N. diplomats and experts, all of whom agreed that Russia and China face an uphill battle to stymie a new U.N. treaty seen as crucial to human rights.

“To all of us who work in the trenches, there’s a sense of excitement among legal experts at the U.N. that there will actually be steps forward on this issue now,” said one U.N. diplomat, who spoke on condition of anonymity to candidly discuss sensitive internal U.N. matters.

The diplomatic battle is playing out against the backdrop of a surge in crimes against humanity in the past year, from Russian war crimes in Ukraine to Myanmar’s brutal crackdown on pro-democracy movements to the devastating conflict in Ethiopia that has killed an estimated 600,000 to 800,000 people. A U.N. convention on crimes against humanity could create a legal framework for countries to coordinate with one another on finding and bringing to justice perpetrators of crimes against humanity, whether they take place on or off a battlefield.

“Especially since the war in Ukraine, there’s been a real refocusing of international efforts to ensure justice and accountability for crimes,” said Akila Radhakrishnan, president of the Global Justice Center, a nonprofit advocacy group.

The origins of a U.N. convention on crimes against humanity can be traced back to the Nuremberg trials prosecuting Nazi war criminals in the aftermath of World War II, when the Geneva Conventions on humanitarian treatment during war and the U.N. Genocide Convention were first adopted. International legal experts for decades have called for the United Nations to create a new convention on crimes against humanity to fill the legal gap not already covered by international conventions addressing genocide, torture, war crimes, enforced disappearances, or apartheid. Crimes that could slip through these international legal cracks include murder, enslavement, rape, forced sterilization, unjust imprisonment, and others that take place outside of war zones or genocides.

“Crimes against humanity is the only Nuremberg crime that’s not codified yet in international law in an interstate treaty,” said Leila Nadya Sadat, an international law professor at Washington University in St. Louis. “So it’s a very important missing piece of the international legal architecture.”

Human rights advocates point to Iran as one example. Iranian officials involved in the brutal crackdown in recent months on protesters demanding basic rights for women may not have committed genocide or apartheid, but they committed something, and human rights advocates said those officials could face accountability in some form if there was a widely adopted international legal framework on crimes against humanity.

“It’s really important because there shouldn’t be a ‘hierarchy’ of atrocity crimes where genocide gets prevention and punishment and crimes against humanity don’t,” said Shannon Raj Singh, co-chair of the International Bar Association’s War Crimes Committee. “At a fundamental level, a victim is a victim, regardless of whether a perpetrator intends to destroy a group or not.”

In 2013, the International Law Commission (ILC), a body of legal experts charged with drafting proposed new conventions for the United Nations to consider adopting, added crimes against humanity to its ever-growing to-do list. In 2017, it drafted an initial set of articles for such a convention, and in 2019, it formally sent the draft to the U.N. Sixth Committee, the body that oversees international legal issues.

The Sixth Committee runs by a peculiar set of arcane traditions and wonky legalistic processes. Russia and China hoped to effectively kill any chance of a U.N. convention on crimes against humanity by bogging it down in an endless carousel of procedural hurdles, debates, and diplomatic heel-dragging, U.N. diplomats and experts tracking the issues said. They pulled it off in 2019, 2020, and 2021.

But a new coalition of countries decided to buck that trend in 2022. When the Sixth Committee met in October, its initiative caught Moscow, Beijing, and its allies off guard. Instead of following a ponderous procedure, Mexico and its allies took the draft resolution already written up by the ILC and introduced it into the committee immediately, assigned coordinators from the outset without waiting for approval from the states that opposed the initiative, and set a timetable for debating the resolution before Moscow and Beijing could mount any opposition to the process.

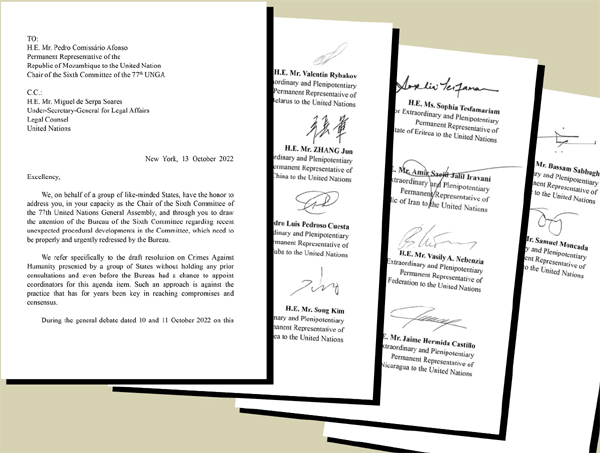

“We are shocked that through the Secretariat of the Sixth Committee, delegates from certain Missions announced themselves to be the coordinators for the draft resolution on Crimes Against Humanity,” Russia and China’s U.N. envoys wrote in an internal October letter to Pedro Comissário Afonso, Mozambique’s ambassador to the United Nations, who held the rotating chair of the Sixth Committee. “It is obviously contrary to the transparency, democracy and legitimacy of the long-lasting working methods of the Committee.” The letter was co-signed by U.N. envoys from North Korea, Iran, Belarus, Syria, Venezuela, Cuba, Eritrea, and Nicaragua.

An October letter to Pedro Comissário Afonso, Mozambique’s ambassador to the United Nations, from the U.N. envoys of Russia, China, and other countries. Read the full letter here.

But what Mexico did was all aboveboard, if untraditional, according to the rules of the Sixth Committee. In another internal U.N. letter obtained by Foreign Policy to those delegates, dated a week later, Afonso wrote that the Sixth Committee “carefully considered the concerns” in their letter, but “the procedures and practices of the Sixth Committee are being followed and honoured.”

From there, support for Mexico’s initiative snowballed. The resolution initially had eight co-sponsors: Mexico, widely seen as the leader of the initiative, Bangladesh, Costa Rica, Colombia, Gambia, the United States, the United Kingdom, and South Korea. Then, dozens of other countries signed on.

“It went from one to eight to 86 co-sponsors,” said Richard Dicker of Human Rights Watch, an international nonprofit organization.

The Sixth Committee traditionally operates by consensus—meaning if one state opposes a motion, the motion effectively fails without needing to trigger a vote. But by that point, U.N. officials and experts said, Beijing and Moscow knew they were checkmated. They could either declare their opposition, trigger a vote on the resolution, and lose—by a wide and very diplomatically embarrassing margin—or grudgingly go along with it. After weeks of angry behind-the-scenes warnings and handwringing, they chose option number two.

“It really upset Russia and China, but at the end of the day, it was a smart strategy that got the resolution to actually move forward for once,” Radhakrishnan said.

U.N. diplomats and experts said the unusual coalition of countries backing the new U.N. convention—from Gambia to Bangladesh—also undermined a common accusation from Russia and China that human rights initiatives at the United Nations only serve to advance the interests of Washington and its European allies.

“You had many states from different regions joining on as co-sponsors with the effect of negating the claim that, ‘Oh, these are just Western countries that care about this and are going to use it against us on account of the invasion of Ukraine,’” Dicker said.

From here, a committee will convene to debate the substance of the draft articles and present them to the U.N. General Assembly in the autumn of 2023, with an eye toward turning it into a full treaty for U.N. powers to adopt. No legal expert believes that a new U.N. convention on crimes against humanity would stop such crimes from being committed overnight. But it would be the first of its kind to explicitly hold states and individuals accountable on such crimes and help grease the wheels on international cooperation for documenting and prosecuting crimes against humanity.

More importantly, it would present states with a legal duty to prevent such crimes regardless of whether those crimes happened in that country or not—similar to what is laid out under the Genocide Convention. It would mandate that states that signed onto the treaty incorporate preventing and prosecuting crimes against humanity into their own national legal system. (Even advanced democracies don’t always have such laws on the books. The United States, for example, has large loopholes in its laws for prosecuting perpetrators of crimes against humanity, something senior U.S. lawmakers are currently working to fix.)

Over time, legal experts and human rights advocates hope, such a U.N. treaty could strengthen accountability and prosecution as well as have a broad, if difficult to measure, deterrent effect on governments that otherwise would commit crimes against humanity with impunity.

“We’re in a difficult moment globally now because of rising authoritarianism and conflict,” Sadat said. “And so I think it’s easy to become really cynical about the power of international law. But it’s also important to remember that without international law, you literally have no basis to combat it.”

____________________________________________________________________________

Robbie Gramer is a diplomacy and national security reporter at Foreign Policy. Twitter: @RobbieGramer; Anusha Rathi is an intern at Foreign Policy. Twitter: @anusharathi_ Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Foreign Policy–FP on December 23, 2022. A version of this article appears in print on Dec. 2, 2022, Section A, Page 23 of the New York edition with the headline: Blockchains: What Are They Good For?. EnergiesNet.com reproduces this article in the interest of our readers. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of socially, environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

EnergiesNet.com 12 26 2022