By Javier Blas

Oil is the world’s foremost commodity. Nations fight wars to control it; economies wax and wane based on its price. But oil is also useless without a process to transform it into the stuff everyone needs: gasoline, diesel, jet fuel and petrochemicals. Over the last couple of years, the refining industry became a chokepoint, pushing the cost of turning crude into fuels to an all-time high, in turn inflating gasoline and diesel prices. The “refinery wall” was the buzzword. Now, the bottleneck is easing.

What changed? The world is building new refineries and expanding older ones at a speed unseen in nearly two generations. It may sound counterintuitive given efforts to ease the climate emergency, but oil demand continues to grow and, to accommodate that, oil companies are again investing billions of dollars in new refineries.

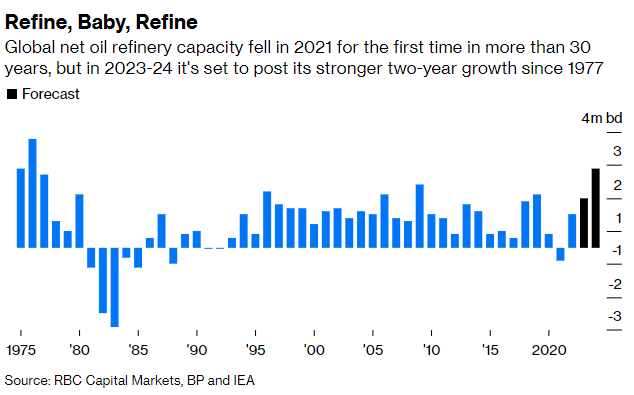

RBC Capital Markets LLC, an investment bank, reckons that net global refinery capacity will increase by 1.5 million barrels a day this year, and by another 2.4 million next year. The combined 2023-24 boost is the largest two-year increase in net global refining capacity in 45 years, according to the bank.

The construction boom matters beyond the oil industry. For central banks trying to decide whether their campaign of interest-rate hikes has subdued inflation, the increased capacity offers some hope that gasoline and diesel prices will stay low.

The buildup is, in part, a fluke: Refinery projects got delayed over the pandemic, with many of them now coming online simultaneously in places such as Kuwait, Nigeria, Mexico and China. Happenstance or not, the increase nonetheless marks a turnaround for the oil industry. In 2021, net global refining capacity fell for the first time in 30 years as the pandemic forced some plants to close.

Exxon Mobil Corp. is emblematic of the new trend. Last month, it fired up the expansion of its plant in Beaumont, Texas. With 250,000 barrels a day of extra capacity, it is the largest addition in the US in more than 10 years.

The new plants are starting to have an impact on the cost of processing crude into everyday fuels. Add pockets of demand weakness here and there, and the result is a significant drop in refining margins over the last few weeks. While both factors are at play, I believe many are over-emphasizing consumption weakness and downplaying the fact that there’s more processing capacity around.

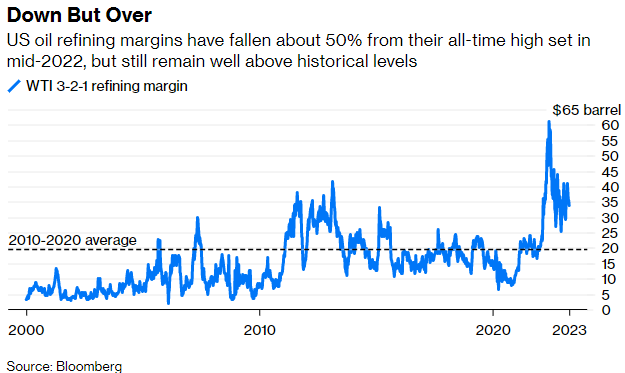

Oil refineries are complex machines, capable of processing multiple streams of crude into dozens of different products. For simplicity’s sake, the American oil industry measures refining margins using a rough calculation called the “3-2-1 crack spread”: For every three barrels of West Texas crude crude oil the refinery processes, it makes two barrels of gasoline and one barrel of distillate fuel like diesel and jet-fuel.

At one point last year, as the global economy struggled to process enough crude into fuels, the WTI 3-2-1 crack spread surged to a record high of nearly $65 a barrel, compared to a 2000-2020 average of less than $15 a barrel. Turning a barrel of crude into gasoline, diesel and jet fuel became so expensive that for consumers, it was like oil was trading at $250 a barrel.

Since then, the American oil refining benchmark has fallen nearly 50% to $32 a barrel — although it remains well above its long-term average. Excluding 2022, current refining margins are among the highest ever, comparable to the 2010-2013 period referred to in the industry as refining’s golden age.

Another factor is pushing margins down: Russian refineries are still operating at high rates despite Western sanctions, defying naysayers that thought they would cut processing after losing access to the European market. Instead, they have found new outlets in Asia, the Middle East, Africa and Latin America.

Going forward, even if petroleum demand growth remains healthy in 2023 and 2024 — and so far, rear-view mirror data suggests it will — refiners are unlikely to repeat the super-charged profits of last year. By historical norms, it won’t be a collapse. After all, current refining margins are nearly double the 2010-2020 average. But the fall would still hurt.

It’s bad news for Big Oil, as companies like Exxon, Chevron Corp., and Shell Plc run big refining businesses, and have gotten used to them performing as cash machines. It would be even worse for pure-player refiners like Marathon Petroleum Corp. and Valero Energy Corp., which have attracted hordes of new shareholders on the back of the 2022 super spike. But for consumers and policymakers, the increase in refining capacity offers welcome relief on the inflation front — if not so much for the climate.

__________________________________________________________

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He previously was commodities editor at the Financial Times and is the coauthor of “The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources.” @JavierBlas. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on April 20, 2023. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

EnergiesNet.com 04 20 2023