- The boost in the country’s output, while auspicious for China, could cause collateral damage in the global oil market.

By Javier Blas

Ask anyone about China and the oil market, and the conversation will invariably focus on voracious consumption — and, perhaps more recently, the surge in electric-vehicle sales. Consistently overlooked is the country’s role as a major oil producer, but the latter matters now because after a years-long lull, Chinese petroleum output is again booming.

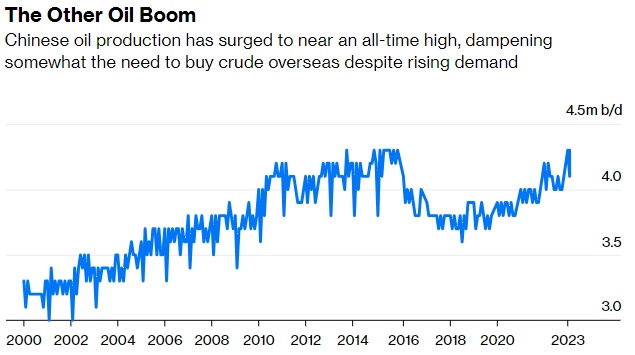

Spending billions of dollars via its state-owned energy giants China National Petroleum Corp. (CNPC), China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. (Sinopec) and Cnooc Ltd., Beijing has been able to reverse the decline in domestic oil production that started in 2015, lifting output this year to a near all-time high. In doing so, the country is somewhat damping the need to buy crude overseas, complicating the efforts of Saudi Arabia and its OPEC+ allies to control the market.

On top of extra Chinese output, OPEC+ is already battling higher-than-expected oil production from several of its own members that are under Western sanctions: Russia, Iran and Venezuela.

From the low point in 2018 to the peak in 2023, China has added more than 600,000 barrels a day of extra production – more crude than some OPEC+ nations generate daily. Pumping about 4.3 million barrels a day now, China is again the world’s fifth-largest oil producer, only behind the US, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Canada, and ahead of Iraq.

The recovery reflects the high priority Beijing places on energy security, having directed its state-owned companies to lift domestic spending in 2019, when the country launched the so-called “Seven-Year Exploration and Production Increase Action Plans.”

Those measures were a response to a sudden drop in Chinese oil output during the second half of the last decade that increased a sense of insecurity in Beijing. From a peak of nearly 4.4 million barrels a day in 2014, domestic production fell to 3.8 million barrels in mid-2018. Three factors contributed: the natural depletion of large oilfields discovered in the 1950s and 1960s, including Daqing (the country’s largest for decades), Shengli and Liaohe; a focus during the early 2000s and 2010s on overseas projects at the cost of domestic ventures (when China spent billions in oil-producing countries like Angola and South Sudan); and overall lower spending on exploration and drilling after oil prices crashed from mid-2014 to early 2016 as OPEC flooded the market in an attempt to bankrupt the US shale industry.

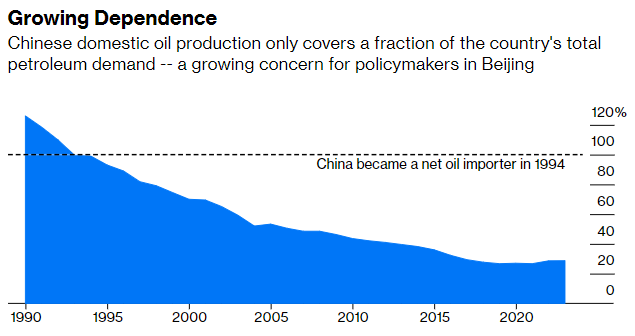

The production decline left Beijing worried about relying too much on foreign energy, particularly because the US and Europe around the same time showed their appetite to use oil as an economic weapon against the Iranian nuclear program.

Since China became a net oil importer in 1994, its dependence on foreign crude has persistently increased. Imported crude accounted for roughly 50% of the country’s oil consumption as recently as 2008. But its share grew as domestic output struggled and demand rose. By 2019, when the seven-year plans were launched, local output only made up 27% of total petroleum consumption, according to Bloomberg Opinion calculations based on official Chinese data. This year, despite rising demand after China abandoned its Covid Zero policy, local production is likely to cover about 29% of the country’s total oil consumption.

To boost domestic output, Beijing is focusing on prolonging the life of its large and aging oilfields, namely those offshore, tapping its shale deposits and, at the margin, relying on unconventional routes — including turning coal into refined petroleum liquids and expanding the production of biofuels.

It’s an expensive enterprise. Last year, CNPC, Sinopec and Cnooc devoted about $80 billion to capital spending – more than Exxon Mobil Corp., Chevron Corp., Shell Plc, TotalEnergies SE and BP Plc combined. Anywhere else, such colossal spending would be seen as wasteful, particularly when measured in barrels of oil per day. But in China, preserving energy independence takes precedence over the profit and loss accounts of its state-owned energy companies. As such, Chinese oil majors are bucking the trend set by US shale companies and Big Oil, which are all tightening their belts to satisfy shareholders that demand bigger payouts via dividends and buybacks.

Whether Beijing can continue boosting production extraction is far more opaque. Sustaining output in mature oilfields has its limits, and Beijing has had mixed success developing its local shale deposits. The International Energy Agency earlier this year said Chinese oil production would decline from 2024 onward, with output falling to 4 million barrels a day by 2028. I’m less sure about that. The events of the past few months, as Russia and the West have used energy as weapons against each other, is likely to convince Beijing that spending more at home to uphold energy production makes a lot of sense, both for economic and military reasons. If so, OPEC+ will suffer the collateral damage.

__________________________________________________

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He previously was commodities editor at the Financial Times and is the coauthor of “The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources.” @JavierBlas. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on July 10, 2023. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

EnergiesNet.com 07 10 2023