John Cordner and Giovann Rosales, Argus Media

LONDON/HOUSTON

EnergiesNet.com 12 18 2023

Venezuela’s threats to annex Guyanese territory have shone a brighter light on the fastest growing source of non-Opec oil supply outside the US and Brazil.

Venezuela’s claims on the Essequibo province that makes up two-thirds of Guyana’s territory go back more than 100 years. But President Nicolas Maduro has stepped up sabre-rattling comments about the territory in recent months because national elections are looming for him next year and he needs to deflect attention from his government’s dire record at managing Venezuela’s economy. Venezuela has increased its military presence on the border with Guyana and ordered ExxonMobil and other oil firms to halt upstream operations in what Caracas says are disputed waters.

Guyana would be a prized target. Crude output has risen by 260,000 b/d since 2021, and the IEA forecasts it will rise by 200,000 b/d in 2024. The country is the centre of an oil boom, which was a principal factor in Chevron agreeing to pay $53bn for US independent Hess, which owns 30pc of the offshore Stabroek field, much of which would become Venezuelan if Maduro’s forces annexed Essequibo.

One result of the Hess deal could be Chevron taking even more Guyanese crude into its own refining system. The major is already the largest US importer of the country’s oil. It takes most of it to its 269,000 b/d El Segundo refinery in California, where it has been importing nearly 70,000 b/d this year, EIA data show. In all, Chevron accounts for roughly 83pc of all Guyanese crude arrivals across US ports this year (see graph).

Unlike other Latin American countries that mostly sell oil through tenders, Guyanese crude is sold through direct negotiations. January-loading cargoes have been trading $1.50/bl below North Sea Dated, after changing hands at premiums of $1.00-1.50/bl in October-November. Deliveries to the US west coast have not been hampered by the drought that has limited shipments of LPG and LNG through the Panama Canal. Crude is transported by tanker to the Panamanian port of Chiriqui Grande and pumped to a Pacific coast terminal by pipeline.

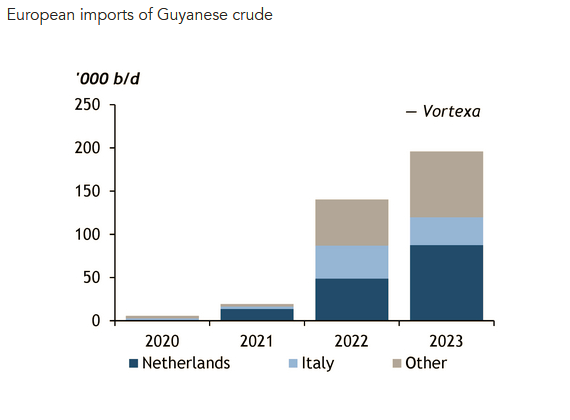

Exodus to Europe

The rapid increase in Guyanese output has also opened up new longer-haul markets. Exports to Europe have risen from less than 20,000 b/d in 2021 to nearly 200,000 b/d this year. But rather than displacing existing crudes, the new flows appear to be plugging some of the gap left by embargoed Russian Urals. Nearly half of Guyana’s crude shipments to Europe goes to the refinery cluster in the Netherlands, followed by Italy with nearly a fifth (see graph).

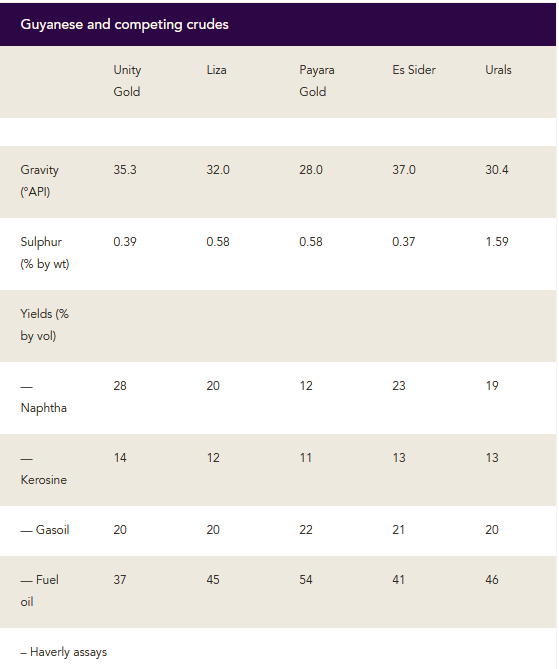

Guyana produces three grades of crude. The two main ones are the 130,000 b/d medium sweet Liza and the lighter 220,000 b/d Unity Gold. Exports of the third — medium sweet Payara Gold — started this month. Europe’s refiners have tended to favour Unity Gold, with its higher yields of transport fuels (see table). Unity Gold is broadly similar in quality to Libya’s Es Sider crude, but less prone to disruption and market participants say it is “more competitive” than the Libyan grade. Greek refiner Helleniq has opted to buy Unity Gold instead of Es Sider at least twice this year, market sources say. But the firm has still increased imports of Es Sider by nearly a quarter to replace prohibited Urals crude.

Some crudes do appear to have been partly displaced by Guyanese crude. Shippers have delivered 14,000 b/d of Angolan Cabinda to Europe so far this year, which is half the 28,000 b/d that arrived in the same period last year. Arrivals of Nigerian Forcados rose to nearly 120,000 b/d from 90,000 b/d over the same period. But Forcados offers a higher diesel yield, which may have resulted in stronger interest for the grade at a time of tight diesel supply this year.

argusmedia.com 12 18 2023