This 2023 review allows us to identify trends in some of the components of the oil market, and how these might evolve in 2024. We risk extrapolating a 2024 similar to 2023, with supply chasing demand. Meanwhile, in Venezuela, production during the year did not show significant changes, evidencing that licenses alone do not lead to the deep recovery required by the Venezuelan oil sector. Furthermore, the system has not been able to satisfy the requirements of the domestic gasoline and diesel market. (Translated: E.Ohep/EN)

By M. Juan Szabo and Luis A. Pacheco

2023 – A Typically Atypical Year

During 2023, the fickle oil market was influenced by a particular mix of facts and perceptions. No sooner had an event or political change occurred in the world, which one believed was relevant and tried to analyze, than the media, in its desire to keep us distracted, replaced it with something different, generally in the opposite direction. Under this avalanche of information, it is difficult to distinguish the wheat from the chaff: it is the new normal, navigating dazed by the volume of information.

The hydrocarbon market has been defined, to a large extent, by three disruptive factors: geopolitical conflicts, including two wars and their reverberations; the evolution of policies and regulations related to climate change; and the reaction of the world economy to monetary restriction policies to fight inflation. Additionally, the emergence of new technologies to reduce or eliminate carbon emissions (CCUS [1], DAC [2]) and the evolution of hydraulic fracturing for hydrocarbons, among other developments, contribute to the perception that hydrocarbons can extend their useful life in the long term. These disruptors significantly impact the dynamics of supply and demand, trade, and investment in the crude oil and natural gas industry, and it is in this context that producers, particularly OPEC+, have to implement their strategy.

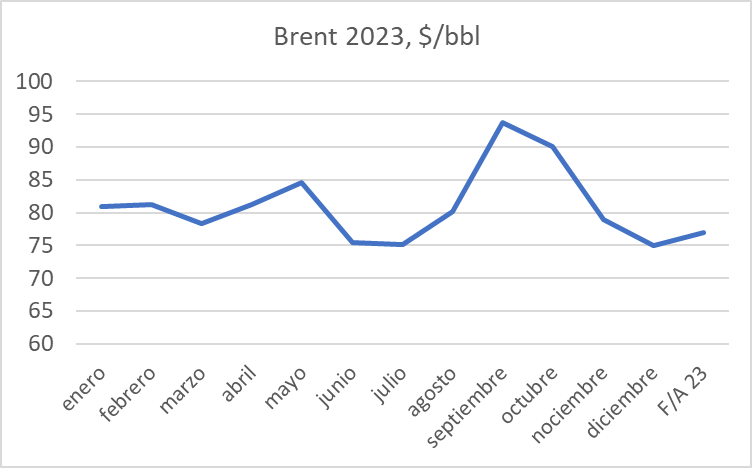

Oil prices, which may have seemed erratic, were nothing more than the result of the interaction of these factors, and perhaps many others. Brent Crude oil surpassed $90/BBL in September, on what some believed was an upward trajectory, only to retreat mid-to-late in the year, approaching $70/BBL.

One dares to postulate that the variability in prices is the result of the struggle between, on the one hand, the fundamentals of the market, and on the other, the interpretation by economic actors of the economic and political environment that we mentioned before – “market perception”.

In this interaction of facts and perceptions, objective figures, such as production volumes and inventories, are confronted against the expectations of market actors. For example, in 2023, there was repeated talk of the inevitability of a recession in the US, emphasized each time the Federal Reserve (FED) increased interest rates by 0.25% (February, March, May, and July), which would affect oil demand. However, the reality was that the US economy turned out to be more robust than expected and demand did not weaken, but still, prices weakened – again, a weird dynamic.

By December, the FED seems to have concluded that they did not need to make additional increases in interest rates, and there is already talk of reducing them starting in 2024, which would point to growth in energy demand. In Europe, the Central Bank is still not convinced to imitate its colleagues in Washington.

This review of the year 2023 allows us to identify the trends of some of the components of the oil market, and how these could evolve in 2024.

Starting with China, the second-largest consumer of oil and the center of attention of the global oil market. Since early 2023, when the COVID-19 economic shutdown was lifted, a wave of optimism emerged around China’s rapid economic recovery. However, that optimism soon turned into uncertainty, which towards the end of the year infected the market with a pessimism that contributed significantly to the 7 consecutive weeks of falling oil prices, apparently due to two main factors.

On the one hand, a good part of the Chinese economy is based on its exports and, therefore, is exposed to the economic health of its markets, which have declined slightly. On the other hand, its domestic demand has not recovered as expected. The government’s efforts to inject the necessary funds to boost consumption were not effective. The over-centralization of the economy that President Xi Jinping is imposing seems to take away the flexibility and responsiveness necessary to manage regional economies, not to mention that the professional bureaucracy is being weakened by the growing use of political loyalty as the main criterion for appointments.

Secondly, OPEC and OPEC+ tried throughout the year to control the oil market to maintain crude oil prices at levels consistent with the budgetary needs of their dominant actors, although the official narrative defines this as keeping the oil market in balance. At the end of the first quarter of the year, the expanded group implemented a production reduction of more than 1.5 MMbpd, which did not achieve the expected effect on prices. While the cuts were announced, Russia, in need to finance its incursion into Ukraine, had managed to place in Asian markets all its crude oil available for export, despite the sanctions, including some additional volumes at the expense of its domestic market. Iran, whose oil is sanctioned by the US and is excluded from OPEC+ quotas, shipped an increasing volume of crude oil to Asia. So, in April, in a renewed attempt to prop up prices, Saudi Arabia announced a unilateral and temporary cut of an additional 1.0 MMBPD; In August, Russia announced a cut of 500 MBPD in exports for the same purpose. Already at the end of the year, OPEC+, faced with the weakening of prices, announced a complex redesign and extension of its members’ cuts until 2024, which sowed more doubts than relief to the market.

The US is another of the fundamental players in the oil market. Its oil production depends mainly on the development of “Shale Oil” basins, and to a lesser extent on the contribution of offshore activities in the Gulf of Mexico. Since last year, its oil companies, under pressure from activist investors, have been more disciplined with their capital investments. That discipline is evident in a reduction in active drilling and in the more intensive use of DUC wells (wells drilled but not completed), resulting in limited production growth while compensating shareholders via dividends and share buybacks. The EIA maintains that US oil production has been increasing to 13.2 MMbpd, a figure that, under the conditions described, seems unlikely; the new year will shed more light on whether the discipline will be sustainable.

These trends, combined with the greater difficulty of obtaining financing because of the fashionable environmental policies, in line with the recently completed COP28, which favors investments in renewable energy, have also limited the growth potential and have encouraged a process of consolidation of operators in the North American market. The premise that justifies this strategy is that the larger size of the resulting companies would allow important synergies that will allow a return to growth path. During 2023, ExxonMobil absorbed Pioneer Resources and Chevron absorbed Hess, both operations paid for with shares; and currently in full development, Occidental announced the acquisition of CrownRock for $12 billion, encouraged by Warren Buffett. These mega-mergers, together with technological developments and strong financial balances, will give a second life to the “Shale Oil” revolution, turning the US into a formidable competitor in international crude oil markets and a headache for OPEC+.

During 2022 and part of 2023, the Biden administration maintained as its oil policy the continuous drainage of crude oil from the strategic reserve (SPR), as a strategy to limit oil prices, to the extent of reducing the SPR from 745 to 348 MMbbls, barely 17 days of net reserve. They are now beginning the reverse process but at an extremely modest rate of 3 MMbbls per month.

Some non-OPEC-producing countries have managed to increase their production during 2023. The most relevant are Brazil and Guyana. Brazil increased about 300 MBPD and Guyana about 100 MBPD, accompanied by other countries with smaller increases, but offset by reductions in other countries. By 2024, Brazil is expected to be part of OPEC+, although initially only as an observer.

Finally, geopolitics has had both positive and negative effects on the 2023 oil market. The persistence of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, which has now been going on for more than 18 months without an apparent solution, has redirected the commercial destinations of at least 5% of global crude oil sales. The other major war confrontation, between Hamas and Israel, in the Middle East, seemed to threaten the oil supply from that region. However, the common goal of the US and China of not affecting oil flows has contributed to the confrontation not spreading to other countries. However, in recent days, several cargo ships and tankers have been attacked by Houthi terrorists from Yemen, in the Red Sea, which is why some shipping companies have suspended the use of that vital shipping lane. We could be in the presence of an escalation that could impact oil prices and other products.

Global demand, despite all macroeconomic brakes, grew by at least 1.7 MMbpd and net supply grew by 0.5 MMbpd. The average price of Brent crude oil in 2023 was around $/bbl 83. With these results, we face 2024, which will begin with less uncertainty regarding inflation and with a lower probability of a recession, at least in the US. Demand will continue to expand, from 1.2 to 2.4 MMbpd, depending on the source consulted, while supply will grow in the US, Brazil, and Guyana, while Saudi Arabia will reduce its voluntary cuts depending on its target price. So, we will risk extrapolating a 2024 similar to 2023, with supply chasing demand, and with Brent crude prices in a band between $/bbl 86 and $/bbl 90, assuming the Middle East manages to limit the war to Israel’s borders with Gaza, the West Bank and Golan Heights.

After 7 consecutive weeks of oil price drops, last week finally saw an increase. Brent and WTI crude oil, at the close of the markets on Friday the 15th, were trading at $/bbl 76.55 and $/bbl 71 respectively.

VENEZUELA

POLITICAL EVENTS

The year 2023 has been a year of profound political, and economic changes and geopolitical redefinition. Although the year began with the dismantling of the so-called interim government, chaired by Juan Guaidó, a sign of the dismantling of the opposition, which seemed in clear retreat, we reached December with an opposition unified around María Coria Machado and a regime disoriented in the face of this unexpected situation.

To the surprise of many, including the regime, the strategy of the referendum on the Esequibo turned out to be unsuccessful and the failure was difficult to hide. This setback, added to the success of the opposition primaries, led the regime to raise the level of confrontation with Guyana.

All the warmongering rhetoric was rejected by Brazil and the CARICOM countries, and Maduro was forced to attend a “pacification” meeting with his Guyanese counterpart. The meeting was held in Saint Vincent and the Grenadines. Maduro was accompanied by the vice president and the defense minister. The Guyanese delegation, led by its president, was accompanied by the highest representatives of CARICOM members, including Trinidad and Tobago. The statement they signed at the end of the meeting, although of little substance concerning the dispute, ended up deactivating the aggressive discourse of the regime. Meanwhile, the parties, in particular Venezuela, are obliged to present their arguments to the International Court of Justice in the first quarter of 2024.

On the other hand, when the allowed period was about to end, December 15, to go to the TSJ, María Corina Machado presented a document requesting that her barring from political office be declared non-existent, an action that surprised the regime, and a part of the opposition. This move expands the political chessboard, forcing the regime to rethink its next step in its objective of not allowing elections that it could lose.

HYDROCARBONS SECTOR

Production

In the oil production sector, it was also a year full of news and changes. In January, crude oil exports to the US market resumed through agreements between Chevron and PDVSA, under OFAC general license No. 41. During the year, Chevron reopened the Boscán field and carried out repair, reconditioning, and maintenance work in all the joint ventures where it participates, resulting in an increase in production of more than 20 MBPD. Likewise, Chevron began to partially replace the diluent supplied by Iran for production in the Orinoco Belt.

Despite this increase, production during the year did not show material changes, remaining in a band between 690 and 780 MBPD, according to OPEC secondary sources. Last week’s production averaged 753 MBPD, of which 141 were produced by Chevron MS, almost 19% of the total. This is evidence, if any was needed, that licenses alone do not lead to the recovery that the Venezuelan oil sector requires.

Refining

Operation at the four major refineries was erratic. El Palito refinery was out of service for much of the year, and since it came back into operation, problems with the distillation tower have limited the operation to only processing intermediate products. Puerto la Cruz refinery operated most of the year at low capacity due to a shortage of light crude oil that has been used preferentially to mix Merey 16 crude oil. The two refineries of the Paraguaná Refining Center, Amuay and Cardón, have operated without continuity because of several fires, problems with the catalytic cracking plants and the reformer, and even a lack of crude oil in specifications. In short, the system has not been able to satisfy the requirements of the domestic market for gasoline and diesel, a situation which has been aggravated by half a dozen shipments of these products sent to Cuba.

Starting in November, under General License 44, gasoline is being imported to alleviate problems in the local market. Chevron is one of the companies that has served as an intermediary for these operations, which are carried out under the barter modality, in exchange for Venezuelan crude oil.

EXPORTS

Crude oil exports handled by Chevron are being sold at international prices. Exports to China, after taking into account the costs of the complex and obscure intermediation system and the discounts required to place sanctioned crude oil, barely generate 50% of the theoretical value of these crude oils. The year was also affected by out-of-spec crude oil issues, which caused delays in loading processes and additional discounts.

As of October 18, under LG44, crude oil could have been sold to customers in the US and Europe at market prices, but this was not the case. The problems of tanker availability, structuring of financial systems, and insurance, necessary for these new destinations, have not been resolved expediently. However, for December, 4.0 MMbbls will be sold to Reliance, in India, probably at prices closer to market. This inability to efficiently redirect shipments caused a reduction in exports in October, November, and early December.

There is a probability, low but real, that, due to the actions of the regime, violating the Barbados agreements and attacking opposition politicians, OFAC will be pressured into suspending the licenses at any time, or in April when the term of license 44 expires. If this were to happen, the production growth of about 200 MBPD, projected for the next 18 months, would not occur. On the contrary, crude oil production would decline as development drilling plans could not be executed.

In the natural gas sector, the Dragon field development project to supply natural gas to the Atlantic LNG plant in Trinidad appears to have encountered a last-minute obstacle, the calculation of the price that Venezuela would receive for the gas sold.

In the unilateral development announced by Trinidad and Shell, to develop the Trinidad side of the Lorán/Manatee Field, on the Plataforma Deltana, the regime indicated that it would hold talks with the Trinidad authorities to reach an agreement to unify the field and perhaps a joint development. Conversations that by the way have already been started and suspended in the past.

ENERGY TRANSITION

COP 28 – Meeting in the Desert.

This December 13, after almost two weeks of deliberations, with the presence of representatives from 200 countries, and nearly 100,000 attendees, the 28th conference of the United Nations on climate change – COP28. Depending on which side of the argument, and on which end of the ideological spectrum the reader falls, the conference was a success or a resounding failure.

The Conference of the Parties ( COP ) is the supreme decision-making body of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), adopted in 1992. It is an annual meeting of the 198 countries that have ratified the Convention, which evaluates the progress made in the fight against climate change and adopts new measures to address this challenge.

The first COP was held in Berlin in 1995, one year after the UNFCCC came into force. In the early years, the COPs focused on the adoption of the protocols and mechanisms necessary to implement the UNFCCC. The most important milestone of this period was the signing of the Kyoto Protocol in 1997, the first legally binding international agreement to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The Kyoto Protocol expired in 2012 and negotiations for a new international agreement intensified. COP 15, held in Copenhagen in 2009, was a turning point, but an ambitious global agreement was not achieved. Finally, at COP 21 in Paris in 2015, the historic Paris Agreement was adopted, setting the long-term goal of keeping global temperature rise below 2°C, and preferably below 1.5°. C, compared to preindustrial levels. Since the entry into force of the Paris Agreement in 2016, the COPs have focused on adopting measures for its implementation. COP 26, held in Glasgow in 2021, was an important step in this regard, with the adoption of the Glasgow Climate Pact, which calls on countries to accelerate climate action.

The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change ( IPCC ) regularly aggregates peer-reviewed research to estimate consensus ranges for climate outcomes under different emissions trajectories. However, these reports recognize the intrinsic uncertainties involved in global climate modeling. The IPCC’s latest assessment predicts a likely warming range of between 1.5°C and 4°C by 2100 if high emissions continue, indicating potentially severe impacts. But other scientists question some aspects of these projections.

There are also differences in the degree of confidence assigned to the attribution of current extreme weather events. For example, while the increase in heat waves is said to be strongly linked to climate change, the divide between natural causes and human-induced changes varies depending on the specific events being analyzed: drought, flood, or storm surge. These areas of uncertainty and the variety of perspectives underscore the complexity of both climate modeling and the intersection of science with global climate policy negotiations.

The host country of the COP rotates among the five United Nations regional groups (Africa, Asia-Pacific, Eastern Europe, Latin America and the Caribbean, and Western Europe and Others) and members of the regional groups determine which country of their region will make an offer to host the conference. The decision to hold it in Dubai was criticized from the beginning, as many considered it inappropriate for the conference to be held in a major oil and gas-producing country (about 3 million barrels per day). Those criticisms became louder when the Emirati Minister of Industry and Technology and CEO of the Abu Dhabi National Oil Company (ADNOC), Sultan al Jaber, was appointed as the president of the summit.

In any case, the conference took place without major setbacks and, as expected, was the scene of controversial conversations, unmet expectations, and some agreements that are worth examining.

Let’s start with the agreement signed by oil and gas-producing companies to reduce emissions from their operations. Saudi Aramco, ExxonMobil, and BP were among the world’s top 50 fossil fuel producers that agreed to a voluntary agreement to stop routine flaring of excess gas by 2030 and eliminate almost all leaks of methane, a powerful greenhouse effect. The success of this agreement will be a function of the intensive use of detection technology, government regulations, and ultimately the economies associated with the initiatives.

Most of the initial signatories were national oil companies, such as Saudi Aramco and Brazil’s Petrobras, which account for more than half of global production but typically face less pressure to decarbonize than their publicly traded counterparts. What they all have in common are emissions of methane, the odorless gas produced by virtually every oil and gas project in the world. When it is not profitable to capture it, companies often release methane into the atmosphere by venting or burning it by flaring, converting it to carbon dioxide. Gas also escapes into the atmosphere from facilities through countless small, undetected, or unreported leaks in pipelines or other equipment, or through large-scale releases called “super emitter” events.

A second COP28 commitment could impact demand for fossil fuels by tripling global renewable energy generation capacity to at least 11,000 gigawatts by 2030. More than 120 countries signed up for this commitment, which will require a major effort from what has been done before. It took 12 years, between 2010 and 2022, to achieve the latest tripling of renewable capacity. This new goal must be achieved in just eight years; It will be “difficult, but achievable,” according to analysts at the BloombergNEF research group who have evaluated the commitment.

Another of the agreements that stands out is the so-called “Loss and Damage Fund”, agreed upon in the first plenary session of COP28. This fund, financed by developed countries, is called to compensate countries with fewer resources for the damage caused by climate change. Some countries committed funds immediately. The $100 million pledge from the United Arab Emirates, the COP28 host country, was matched by Germany, and then France, which pledged $108 million. The United States, historically the worst emitter of greenhouse gases – and the largest producer of oil and gas this year – has so far pledged only $17.5 million, while Japan, the third-largest economy behind the United States and China, has offered 10 million dollars. Other commitments include Denmark with $50 million, Ireland and the EU both with $27 million, Norway with $25 million, Canada with less than $12 million and Slovenia with $1.5 million.

This fund is perhaps the most palpable example of the difficulties of materializing what has been agreed in a well-intentioned document. A recent United Nations report estimates that up to $387 billion will be needed annually for developing countries to adapt to climate-driven changes. Some activists and experts are skeptical that the fund will raise anything close to that amount. A Green Climate Fund, which was first proposed at the 2009 climate talks in Copenhagen and began raising money in 2014, has not come close to its goal of $100 billion annually.

The final declaration of the conference was the subject of long and complex discussions, in fact prolonging the formal closing of the event by 24 hours. The disagreement revolved around the language to be used in the statement about the future use of fossil fuels. The most radical proposal having an agreement on the gradual elimination (“phase out” or “phase down”) of all fossil fuels. Others only wanted to restrict the use of coal, oil and gas, without reducing or capturing emissions. Meanwhile, others proposed alternative formulations linking the expansion of renewable energy to the “substitution” of fossil fuels, adding additional verbs like “accelerate,” adverbs like “rapidly,” or adding time scales like “this decade.”

While the OPEC secretary called for a focus on emissions reductions rather than fuel choices, and instructed its members to oppose any language that could be interpreted as against the continued use of oil, the IEA considered the efforts of emissions capture and sequestration as risky solutions. In short, a complex negotiation, since the 198 signatories of the UNFCCC had to agree to the language of the final declaration.

In any case, an agreement was reached on the language, which probably leaves all parties equally dissatisfied, but which some consider the loudest call in decades for changes in the fossil fuel industry. Will it be enough? Many think not and that fossil fuel producers got away with preventing more restrictive language from being included.

The text of the agreement finally agreed upon encourages, for the first time, countries to move away from fossil fuels and rapidly increase renewable energy. Island states that feel at risk from rising sea levels said the text was an improvement but contained a “litany of loopholes.” Scientists said the document did not go far enough for world leaders to fulfill the promise they made at COP21 to avoid breaching the +1.5°C milestone. In short, it is an imperfect agreement that leaves all parties equally dissatisfied, but that many consider as progress on the steep slope of transforming the energy system on which the well-being of the species depends; After all, today a little more than 80% of the energy the planet uses comes from fossil fuels.

The fact that COP28 took place in an oil-producing country is not without its paradoxes, but on the other hand, it is an example of how energy can transform a desert into an oasis. COP29 will be held in Azerbaijan, another curious choice. If instead of demanding definitive results, or looking for culprits of convenience, the discourse focused on dealing with the management of risks and benefits, this social engineering effort on a global scale, which is the energy transition, could end up being a more useful tool.

___

[1] CCUS: Carbon Capture Utilization and Storage

[2] DAC: Direct Air Capture

- The illustration was generated using Midjourney, by Luis A. Pacheco, courtesy of the author to the publisher of La Gran Aldea.

__________________________________________

Juan Szabo is a Mechanical/Petroleum Engineer with B.S. and M.S. degrees from the University of Houston with over 50 years of experience in oilfield services companies, international integrated companies, national companies, small public and private companies. He has advised on energy issues to oil companies, investment funds and multinational institutions. Luis A. Pacheco, Nonresident Fellow, Center for Energy Studies, Rice’s University Baker Institute for Public Policy. The views expressed are not necessarily those of EnergiesNet.com.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published in La Gran Aldea on December 19, 2023 and reproduce in English in El Recadero. We reproduce it for the benefit of readers. EnergiesNet.com is not responsible for the value judgments made by its contributors and opinion and analysis columnists.

Usage Notice: This site contains copyrighted material, the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We make such material available in our effort to advance understanding of issues of social, environmental and humanitarian importance. We believe this constitutes a “fair use” of such copyrighted material as set forth in Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act. Pursuant to Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107.

For more information, visit: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml

EnergiesNet.com encourages individuals to reproduce, reprint, and disseminate through audiovisual media and the Internet, Petroleumworld’s editorial and opinion commentary, provided that such reproduction identifies, the author, and the original source, http://www.petroleumworld.com and is within the fair use doctrine of Section 107 of the U.S. Copyright Act.

Energiesnet.com 12 24 2023