By José Enrique Arrioja

GEORGETOWN — If there’s a symbol of both the immense promise and risks of Guyana’s future, it might be the project known as Silica City.

The brainchild of President Irfaan Ali, the goal is to build an entirely new “smart city” in the tropical savannah some 30 miles south of the capital, Georgetown, near the international airport. Close to $10 million in construction contracts were awarded in February 2023; there are plans for an 18-hole golf course, housing for 60,000 people, schools, industrial parks and more. Architects from the University of Miami will help design Silica City’s master plan; investors as far away as Singapore and South Korea have expressed interest. The government says it may take 20 years to finish, but it expects people to start living there as soon as this year.

For now, it’s little more than an empty field. When I visited on a Friday morning in November, getting to the construction site required crossing two wooden, single-lane bridges. A handful of ununiformed workers were setting the foundations of future streets and sidewalks; there were a few cement mixers, but no cranes or generators. The only real sign of the project’s scope was a cursive “Silica City” sticker attached to the side window of a contractor’s SUV.

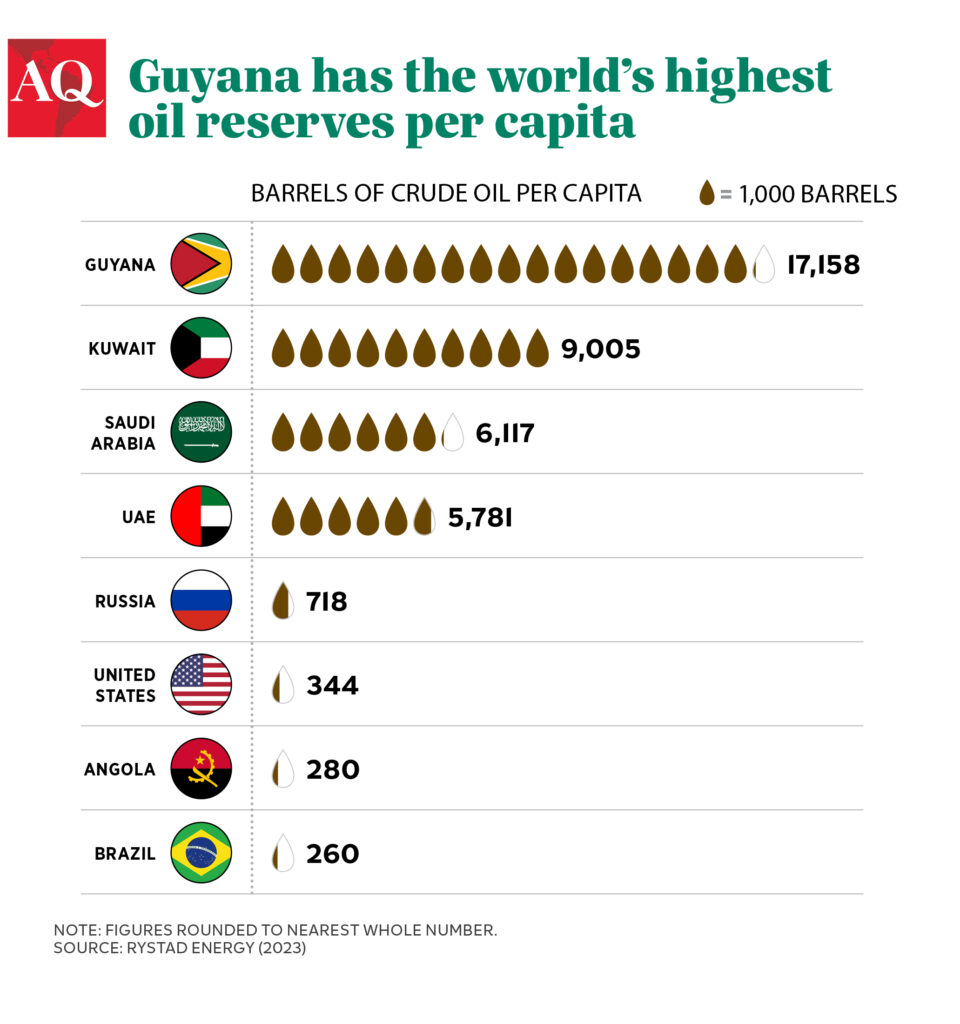

Such is life, perhaps, in a country still in the early stages of a potentially transformative oil boom. It has been eight years since the discovery off Guyana’s coast of oil now believed to total 11 billion barrels. That would be a huge find for any nation, among the top 20 reserves worldwide. But for Guyana, a country of only 800,000 people, it means more oil on a per-capita basis than even Saudi Arabia. With the economy already growing at a 38% pace in 2023, and an estimated 21% in 2024, some are calling this “South America’s Dubai,” a place where no idea—even a new city—is too ambitious.

But anyone with a sense of history knows Dubai is not the only possible outcome—that oil for many countries has been less of a blessing than a curse. My native Venezuela is just one example, along with Angola or Congo, of how sudden resource wealth can fuel social conflict, destroy democracies and hollow out other productive sectors of a nation’s economy. Large-scale building projects like Silica City have, in other countries, sometimes become monuments to inefficiency and waste.

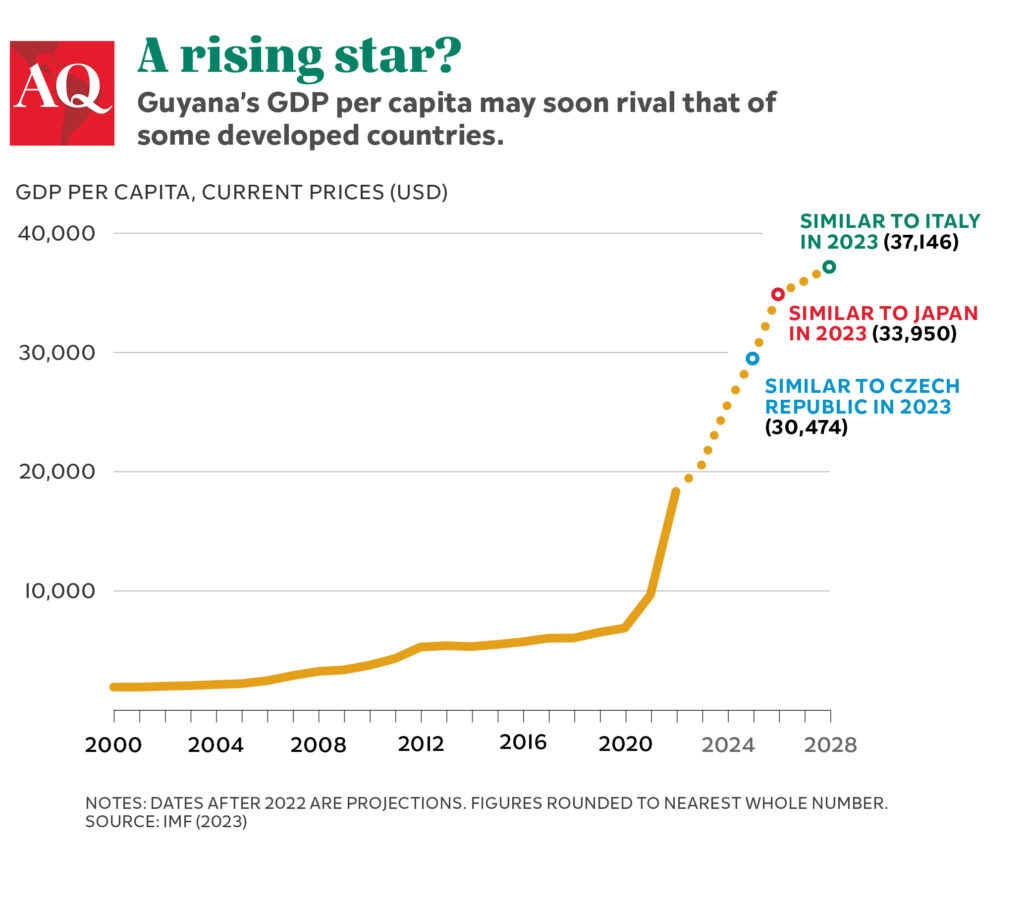

During a week-long trip to Guyana, I interviewed numerous government officials as well as members of the political opposition, civil society, the private sector and everyday people. I saw clear signs of promise: plans for new schools, hospitals and critical infrastructure befitting a country where, according to projections by the International Monetary Fund, per-capita GDP could theoretically rival Italy or Japan by the end of this decade. But I also saw how far Guyana still has to go: narrow roads, derelict buildings, piles of garbage in the streets and polluted water canals, testimony to a country still suffering from 12% unemployment and 48% poverty even amid this incipient boom.

The government says it is fully aware of the risks—and learning from other countries’ past mistakes.

“There is no resource curse; the resource is a blessing,” President Irfaan Ali told me in an interview. “It’s a management curse, and we are doing everything to avoid that.”

“We are not building an energy nation; we are building a diversified economy that is focusing on many areas of growth,” Ali said. In fact, Silica City is meant to be a hub for technology professionals and other industries currently struggling for space in the crowded capital, Georgetown. Resources from the oil industry will fund investments needed in tourism, food production, industrial development, manufacturing and biodiversity services, which will be “major growth areas of the future,” Ali said.

“We are not building an energy nation; we are building a diversified economy that is focusing on many areas of growth.”

— President Irfaan Ali

I heard similarly confident messages from others in Guyana. But there were also plenty of questions: Can a country with a history of ethnic tensions find a way to equitably share this extraordinary wealth? How to avoid the slide toward one-party rule that has plagued so many other oil-rich nations? Is it ultimately self-defeating for a nation in the Caribbean, one of the regions of the world hardest hit by climate change, to bet so aggressively on oil? Will any other parts of the economy be able to compete?

“In Guyana, the risk of the resource curse is particularly strong,” Jay Mandle, an economics professor at Colgate University and a member of the University of Guyana Green Institute Advisory Board, told me. To overcome the risk, he said countries must usually nurture a robust private sector, with companies that “can withstand the temptation of confining themselves to the market provided by the energy sector, which becomes a very strong magnetic force.” But he pointed out that almost all Caribbean nations including Guyana lack a strong private sector, a challenge he described as partly a legacy of colonial rule. “It’s not just having adequate public policy,” Mandle said. Rather, it involves a much, much greater set of challenges.

A Legacy of Division

Managing such a quantum leap in development would be challenging for any country—but perhaps especially for a nation as young as Guyana.

A former British colony, Guyana achieved independence only in 1966. In the years since, there have been repeated power struggles between the country’s ethnic Indian and African communities, which account for approximately 40% and 30% of the population, respectively. On a visit in 2015, former U.S. President Jimmy Carter spoke of a longstanding “winner-takes-all custom” in Guyana’s politics and said, “Efforts to change this system to a greater sharing of power have been fruitless.”

(See AQ’s illustrated guide to Guyana’s history and economy.)

The most recent elections, in 2020, were plagued by allegations that the then-ruling party coalition, A Partnership for National Unity + Alliance for Change (APNU+AFC), tampered with the vote. Only after a five-month legal battle did Ali’s People’s Progressive Party/Civic (PPP/C) take office, with the narrowest of majorities: 33 of 65 seats in parliament.

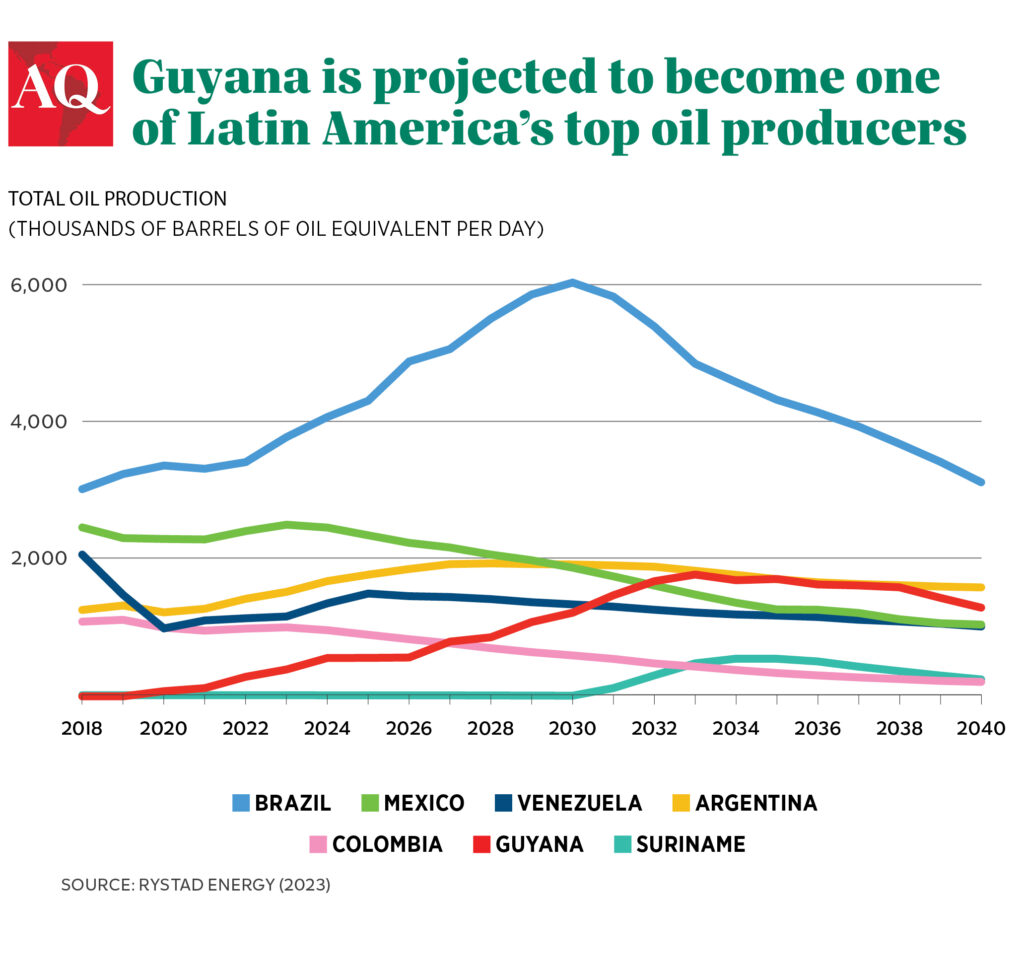

That’s a questionable political framework for handling the abundance expected to pour in over the next decade. Guyana has gone from producing 75,000 barrels of oil per day (bpd) in early 2020 to over 550,000 bpd today, on its way to a projected 1.2 million bpd by 2027. That would be about as much oil production as today’s Qatar—a comparison that seems especially apt, given the countries’ relatively similar size and, perhaps, economic ambitions.

“Guyana is very important because it is the fastest offshore oil development in the history of the world,” Daniel Yergin, an author and member of the U.S. Secretary of Energy Advisory Board under the last four presidents, said in a recent interview with CNBC.

Oil has also posed new geopolitical challenges. In late 2023, tensions increased with Venezuela after its dictatorship revived a decades-old controversy over Guyana’s Essequibo region. The two countries’ leaders agreed to try to reduce tensions, but some expect Venezuela will be tempted to reassert its claims as revenues from the disputed region grow larger in coming years.

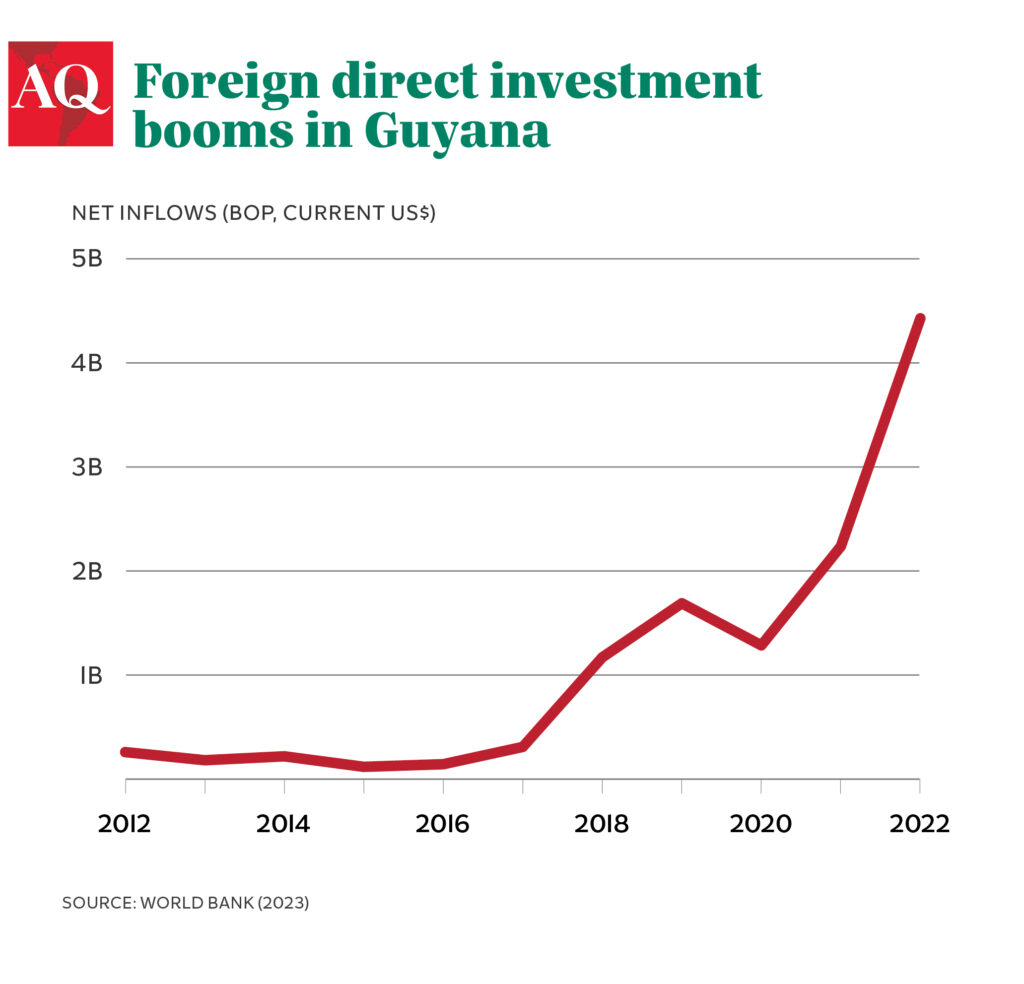

Indeed, the windfall is only starting. Contracts signed with ExxonMobil, Hess Corporation (recently acquired by Chevron) and China’s CNOOC enable Guyana’s government to receive 2% of oil production as royalties. After the companies deduct their operational expenses and recovery costs, they split the profit 50/50 with the government. Guyana’s coffers netted $1.2 billion in proceeds from these arrangements in 2022—a number that could reach more than $10 billion annually by 2030 once additional oil output and vast natural gas resources come online.

The fight over the money, and how it will be distributed among political parties and ethnic groups, is already at full tilt. When U.S. Secretary of State Antony Blinken visited Georgetown last July, Aubrey Norton, the leader of the opposition, warned him that “a one-party state is emerging” in Guyana. The fear is that oil wealth will give the governing party so many resources that it becomes almost impossible for it to lose elections—a classic phenomenon in petrostates worldwide.

Francisco Monaldi, a scholar and energy expert at Rice University’s Baker Institute, said the association of Guyana’s political parties with specific ethnic groups is concerning. In broad terms, Ali’s PPP/C party is associated with people of Indian descent, while Norton’s People’s National Congress Reform (PNCR) is seen as representing the Afro-descendant community. Although there are nuances, this system means “the government has to be very transparent to the sector not in power so that it won’t feel excluded from the national plans,” Monaldi said.

“In the long run, that could lead to social conflicts that may derail Guyana’s development process,” he said.

Hospitals, Schools and More

Local and foreign observers have recommended reforms and new institutions precisely to prevent a future conflict. Desmond Thomas, coordinator of the Electoral Reform Group, a civil society advocacy organization seeking to improve the nation’s institutional framework, suggests new campaign finance rules as well as ensuring all parties have access to the local media in order to level the playing field.

“I believe that if we fix the electoral system, that at least will get us working together,” Thomas said.

After the disputed 2020 election, a European Union mission suggested more than two dozen reforms, including forbidding the use of state resources for campaigning; transforming state-owned media into a genuine public broadcaster; and a new dispute resolution body. But a delegation led by Spanish lawmaker Javier Nart concluded last June that several of these recommendations were still pending, even as Guyana heads toward another election in 2025.

Vice President Bharrat Jagdeo, widely perceived as one of the country’s most powerful leaders, downplayed concerns about a disruptive split ahead. He told me members of all ethnic groups are well-distributed across the parliament and the judiciary, and cited previous reforms to promote a more inclusive, integrated society. Prosperity may also help paper over some divisions, he contended. “When the middle class grows, the country becomes more stable,” Jagdeo told me.

Meanwhile, efforts are underway to spread the wealth. The government has committed $406 million to the health sector, primarily to build or expand 12 hospitals, including two regional hospitals, the construction of a new pediatric and maternal facility, and the building of six additional regional health care facilities. Well-known companies in the industry, such as Mount Sinai Health System, are already working in partnership with Hess Corporation to improve the operations of Georgetown Public Hospital, the nation’s largest. Under the agreement, Hess committed to invest $32 million, while Ali’s administration will contribute $1.6 million.

The government has also increased monthly payouts to pensioners like Hari Persaud, an 86-year-old who cut cane most of his working years at the nearby Versailles sugar estate. For the past two years, Persaud has received a one-off bonus in December equivalent to more than $200, he told me one afternoon at his house in West Bank Demerara, on the outskirts of Georgetown. “I wish the government would give us education; we can have money, but without education, we are nobody,” he told me. The government has also granted more than 20,000 scholarships.

“I wish the government would give us education; we can have money, but without education, we are nobody.”

— Hari Persaud, retired sugarcane cutter

The opposition party has pushed for more—including the distribution of cash payments to the poor. But the government has been hesitant. “There is a misleading view that we are awash with money, and that’s not so,” said Jagdeo, the Vice President. “We have to stick to our plan and not get carried away with populism.”

Many outside experts acknowledge patience is needed. “Policymakers are now presented with the task of converting this dizzying pace of growth into an improved socio-economic reality for all people,” Yeşim Oruç, the UN Resident Coordinator for Guyana, told me via e-mail. “We know from experience around the world that this can be difficult. It takes time. There are no shortcuts.”

A Focus on Institutions

On the economic front, Guyanese officials speak convincingly about the risks of oil. But when it comes to long-term plans, the details can sometimes seem scarce.

Jagdeo told me Guyana’s difficult past makes it especially attuned to the need for smart fiscal management. At one point prior to the oil discovery, 94% of the country’s fiscal revenue was earmarked to repay debts, and the budget deficit was equivalent to 25% of GDP, he said. With decimated infrastructure and triple-digit inflation, many fled the country; about half the Guyanese population lives abroad, mostly in the United States and Canada.

“We are painfully aware that it requires even greater vigilance and fiscal discipline in this period. Windfalls are great if you use them well,” Jagdeo said at his party’s headquarters. “If you don’t make good use of them and don’t improve the welfare of society, they can be harmful.”

Progress on institutions that could manage the wealth over time has been slow, observers say. A sovereign wealth fund, known as the Natural Resource Fund, was created in 2019 and amended in 2021 to help the government finance its development priorities. The fund’s resources are deposited in Manhattan’s Federal Reserve Bank of New York, and the parliament approves annual transfers to the national budget. Last year alone, the contribution reached $1 billion.

While the fund is considered a step in the right direction, analysts point out that Guyana should continue with the creation of infrastructure and education funds to improve resilience and broader development. “Moving from a raw commodity-exporting economy to a services-based economy is not an easy task,” said Schreiner Parker, a managing director for Latin America at Rystad Energy, an Oslo-based research and business intelligence consultancy firm. “But through infrastructure and education investment, the chasm becomes less wide and the ultimate goal more attainable.”

“Moving from a raw commodity-exporting economy to a services-based economy is not an easy task.”

—Schreiner Parker, managing director for Latin America, Rystad Energy

The opposition and observers have also called for the creation of a new Guyanese Petroleum Commission, similar to those in Brazil or Colombia, with the goal of removing day-to-day, partisan political considerations from industry management as much as possible. “The need for a system of checks-and-balances in the petroleum sector is imperative to avoid undue accumulation of power, and frankly, temptation,” Parker said.

But such a move is not imminent, officials told me. Vickram Bharrat, the nation’s Minister of Natural Resources, called an oil commission “something in the making,” but declined to say if it will be created in 2024. He said the administration already has a legal framework in place so the oil industry can operate in a “transparent and accountable manner,” with “adequate checks and balances.”

International development banks, including the Inter-American Development Bank (IDB), the nation’s largest multilateral creditor, are also trying to provide advice and funding to help Guyana avoid the resource trap. In 2022, the bank approved ten operations in the country for $460 million and 32 technical cooperation agreements for $18 million, for projects focused on resilient infrastructure development, human capital development in health and education, and strengthening Guyana’s institutions.

The formation of a national oil company similar to Pemex in Mexico or Petrobras in Brazil is out of the question, several officials including President Ali told me. Creating a state-owned company would require too much capital, and a managerial capacity Guyana currently lacks, they said. “We have seen experiences with state oil companies, and we are not ready for that,” Jagdeo said.

Instead, the money is being steered toward long-term development plans. At present, the main link between Guyana and Brazil is a single-lane, red-clay road—one that Guyana plans to upgrade to a two-lane asphalt road. A planned bridge to Suriname will allow Guyana to sell more manufactured and agricultural products to its neighbor, which is also enjoying a surge in oil production. Completing the trade push, Ali’s administration is leading CARICOM’s 2025 food security initiative, which seeks to increase food production and intra-regional trade by 25% in that year.

It’s all a heady change for a country that just a decade ago had gold, rice and sugar as its top exports. Guyana’s Finance Minister Ashni Singh told me the government wants to expand agriculture beyond sugarcane and rice, planning the large-scale production of new crops such as corn and soy that will supply the domestic market and, eventually, the rest of CARICOM.

Whether these new sectors can cope with inflation and other side effects of the oil boom remains to be seen. While I was in Guyana, a single room at the Marriott Hotel cost $380 before taxes. Several other downtown hotels had no vacancies, a common problem these days. Restaurant prices sometimes seemed reminiscent of New York: A humble meal of chicken and picanha in a rodizio-style restaurant on Alexander Street cost me $42. Inflation is projected to remain above 5% for years to come.

The oil sector directly employs only about 6,000 workers. For other Guyanese, the pressure on prices has been tough to cope with. “Salaries are going one way, and the prices in a completely different direction,” one woman told me while lunching at a Popeye’s fast-food restaurant downtown, where I also went to find a cheaper meal. “At least I have a job. I don’t know how people manage to make ends meet,” she added.

Climate and Other Challenges

Looking ahead, several challenges are on the horizon.

Guyana is starting to produce oil at a time when net-zero emissions is a prominent objective in a climate change-driven world, and when much of the global agenda spins around decarbonizing economies. “We have a narrow timeframe to profit from,” Jagdeo said, referring to the peak oil theory, but avoiding discussing the details of such projections. “We want to create an environment for accelerated (oil) production.”

Showing the balance the country is trying to achieve, a green economy is also touted as priority. Ali wants Guyana to maximize the value of the nation’s forest, a principle already stated in the Low Carbon Development Strategy 2030, he said. In 2022, Hess Corporation agreed to buy $750 million worth of carbon credits from Guyana under the United Nations Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation program (REDD). In 2009, Guyana also signed a $250 million deal with Norway to protect 18 million hectares of forest.

Meanwhile, development of the oil sector is proceeding at warp speed. Minister Bharrat estimates that over $50 billion will be invested in the oil sector this year, mainly in the Statbroek area operated by the joint venture led by ExxonMobil (45%) with Hess (30%), and CNOOC (25%). The block is still the only producing field in the country, and while I was visiting Georgetown, the companies announced that a third floating production, storage, and offloading (FPSO) vessel, Prosperity, started formal extraction operations.

Companies like Total, Repsol and others are also expected to enter the production phase soon. The amount of money to be invested in the sector will “probably double” by 2030, according to Bharrat, as the country plans to have as many as 10 FPSOs in operation. Additional capital inflows will come to the gas sector “very soon” under the Natural Gas Strategy, he added.

What will happen to all that money? In my conversation with Norton, the opposition leader, he complained repeatedly about the administration’s strategy of putting so much money into large-scale infrastructure projects. “We are on a trajectory of waste,” he said, expressing doubts about the government’s institutional capacity to plan and execute so many initiatives in coming years.

“What Guyana needs at this stage is a holistic plan,” Norton said.

Some analysts agree. Thomas Singh, a longtime professor of economics and director of the University of Guyana’s Green Institute, also sees a lack of planning. “I’m worried that the government is too focused on vacuous growth numbers while not paying attention to more meaningful social issues,” he said.

When I asked President Ali if his government’s present and future ambitions were consolidated in some kind of master plan, he said, “I’ve been writing a plan as we go along, because we don’t have the time to have a plan and then implement it.” But he also said the government intends to announce a new initiative, called the “One Guyana Developing Strategy,” in January, that will spell out the country’s pillars for growth going forward.

In my conversations with the president and other officials, it was clear there is no lack of grand plans in today’s Guyana. Ali spoke of a country that will use its newfound wealth to properly preserve its forest, while also building infrastructure that will “position Guyana as the number one player on food in the region,” allowing it to export to the Middle East and elsewhere. The country also hopes to develop its diplomatic might, taking a seat this year as a non-permanent member of the United Nations Security Council. In the future, there won’t be an international forum on climate, food or energy “where Guyana will be absent,” Ali said.

Ali suggested he is all but certain to seek reelection in 2025. “I’m not looking for a legacy at this moment,” he told me. “All I’m doing is working hard every day … putting all my focus and energy on the advancement of Guyana.” Many others will be doing the same.

This article was updated on January 23 to reflect the most recent oil production data.

___________________________________________

José Enrique Arrioja, the managing editor of Americas Quarterly and Senior Director of Policy at the Americas Society/Council of the Americas. Former Bloomberg journalist and editor with focus expertise in Latin emerging markets. He has been editor for Latin America since March 2013, overseeing strategic planning for Bloomberg News in the region. Previously, he worked as Mexico City bureau chief from 2009 to 2013, and between 2006 and 2009 he was the executive producer of Bloomberg Television Latin America while also anchoring the shows Reporte Financiero and Intercambio, both produced from New York. Arrioja was also a television reporter for Bloomberg Television Spain. Prior to joining Bloomberg, he was editor of The Wall Street Journal Americas in Spanish from 1998 to 2000. In Venezuela, he reported for the papers El Nacional, El Universal, and was a founder journalist of Economía Hoy. Arrioja has interviewed numerous heads of state and high-level officials, including Hugo Chávez, Evo Morales, Oscar Arias, Álvaro Uribe, and Felipe Calderón. He graduate in journalism from the Andrés Bello Catholic University in Venezuela, and has post graduated studies on new technologies and television at New York University.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Americas Quartely , on January 23, 2024. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

EnergiesNet.com 02 04 2024