If a hydroplant responsible for 30% of the nation’s electricity went offline, it would compound an energy crisis already roiling the nation.

By Peter Millard and Stephan Kueffner, Bloomberg News

Photography and video by Johanna Alarcón for Bloomberg

The $3 billion Coca Codo Sinclair hydroelectric power plant in Ecuador has been a public relations disaster since its inception nearly a decade ago — for its construction flaws, cost overruns and a corruption scandal.

But its location is proving the biggest problem of all. The facility, from which Ecuador gets almost a third of its electricity, is on the verge of slipping into a sinkhole. That could compound an energy crisis in a South American nation that’s already been crippled by 14-hour rolling blackouts and power rationing.

Coca Codo Sinclair, a roughly three-hour drive from the capital of Quito, sits in a valley prone to natural disasters and the resulting erosion could reach the plant’s water intake facility as early as 2026, according to a study from the US Army Corps of Engineers seen by Bloomberg News. Plus, a slow-motion avalanche of sediment from a waterfall collapse could bury another part of the generation facility.

The plant going offline would be disastrous for Ecuador, and only add to turmoil and frustration from residents who are dealing with increasing crime and political instability. For now, the state utility is renting a floating fuel-oil power station off the coast, one of the filthiest sources of electricity, to ease the disruptions to the daily lives of its people. However, given that it would take years to build enough surplus energy generation from solar or thermal power, Ecuador needs to keep Coca Codo Sinclair operational at all costs.

The project was, however, risky from the start: Planners picked a scenic spot for the dam, just up the river from Ecuador’s tallest waterfall and at the base of the Reventador volcano. Any local could have warned against the idea.

Marcos Cahuatijo has witnessed three major geologic events strike the Coca valley in his 54 years — including two earthquakes that struck the same day in 1987 and a volcanic eruption in 2002. A few years later, he led the construction of a residential complex for hydroelectric plant employees near the base of the volcano.

“At night it turned red, and you could hear the volcano spewing out rocks,” said Cahuatijo, as he replicated the gurgling and thumping sound of molten rocks tumbling from the crater.

The only quick fixes are expensive or unreliable. Electricity imports from Colombia have faced interruption as its northern neighbor has temporarily had to cut off supply to keep its own lights on. Most of the natural gas in Ecuador’s oil fields gets flared in an ongoing environmental debacle because the country would need to build a network of pipelines to transport the fuel.

“We will no longer be able to count on this electricity”

“We will no longer be able to count on this electricity,” said Carolina Bernal, a hydrosedimentologist and researcher at the National Polytechnic School in Quito, who has studied Coca Codo Sinclair. “There is nothing that will stop this regressive erosion.”

For now, the state utility has dispatched engineers to shore up the riverbed beneath the plant. But Ecuador seems poised to make the same mistake again, at another hydro facility it’s planning in the southeast.

Coca Codo Sinclair’s precarious location is only inflaming a broader problem: Hydro is responsible for 80% of the country’s electricity needs.

It’s something that’s become familiar to many developing countries where cheaper energy alternatives squeeze out the more costly ones. Hydropower is relatively reliable — until a drought hits — creating a false sense of energy security.

It’s also the reality of many new and carbon-free energy infrastructure projects: They have to rely on natural resources at a time when climate is changing everywhere.

Just look to Zambia and Zimbabwe. Plunging water levels at the world’s biggest man-made reservoir have caused power outages in both countries. Last year, flooding and landslides in Nepal sent hydro projects offline. In the Indian Himalayas, two recently built hydro projects have been swept away by floods since 2021.

The disasters also underscore how the most suitable sites for hydropower have already been occupied, forcing developers to move into more hazardous regions where they often use out-of-date climate models.

Read More: Dams Are Becoming More Dangerous to Build as Good Sites Run Out

“There’s an appetite in the developing world for big projects, mega projects,” said Homero Paltán, a water and climate researcher at the World Bank and the University of Oxford. “But there’s also a lack of preparedness and awareness in terms of acknowledging climate and water risks.”

President Daniel Noboa, who is campaigning for re-election, has vowed to finish another hydro project and widen a transmission line to import electricity from Peru among plans to pivot away from overreliance on hydropower. He blames the current crisis on his predecessors.

Coca Codo Sinclair in particular was part of former President Rafael Correa’s efforts to show the world how Ecuador could modernize itself without help from Western lenders.

In 2008, Ecuador state utility Celec tapped Sinohydro, a subsidiary of Power Construction Corp. of China, to build the plant. The government would later go on to pursue arbitration against the contractor for construction flaws.

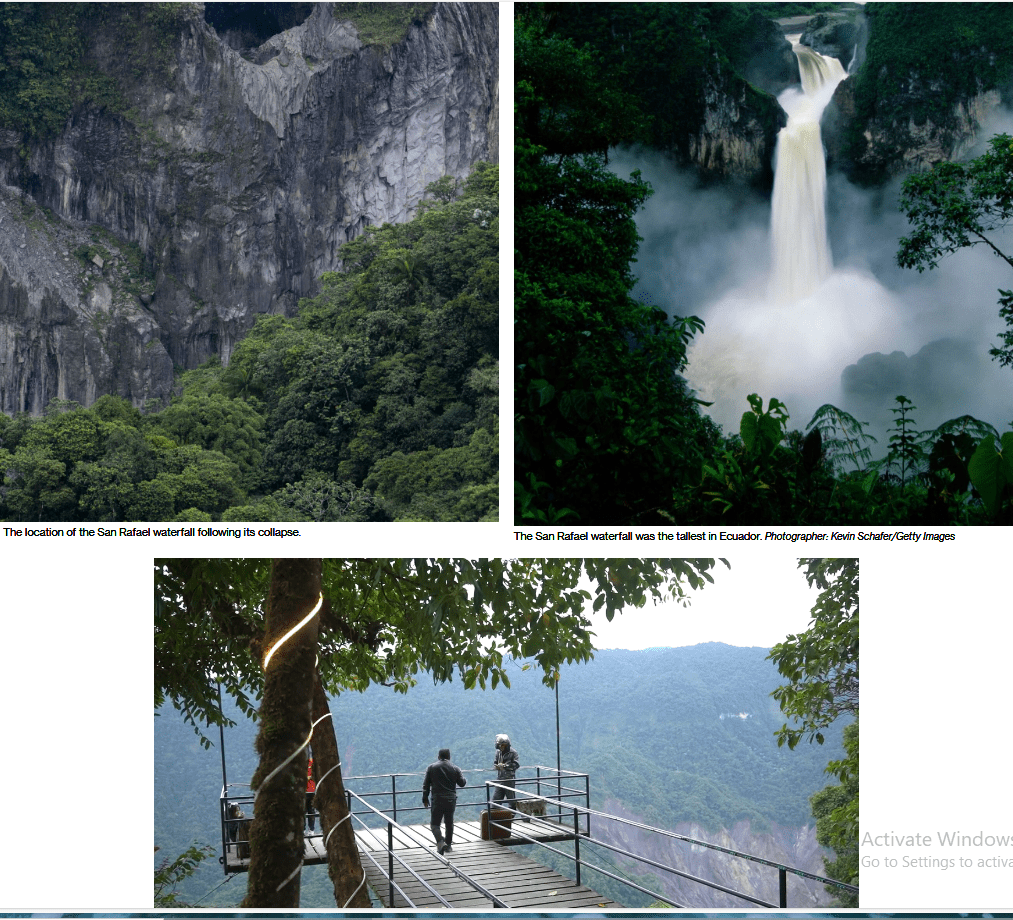

Four years after hydro operations started in 2016, another geologic event struck the Coca valley. A natural lava dam that had supported the 490-foot San Rafael waterfall collapsed, unleashing landslides and eroding out the riverbed leading up to hydroplant’s water intake facility.

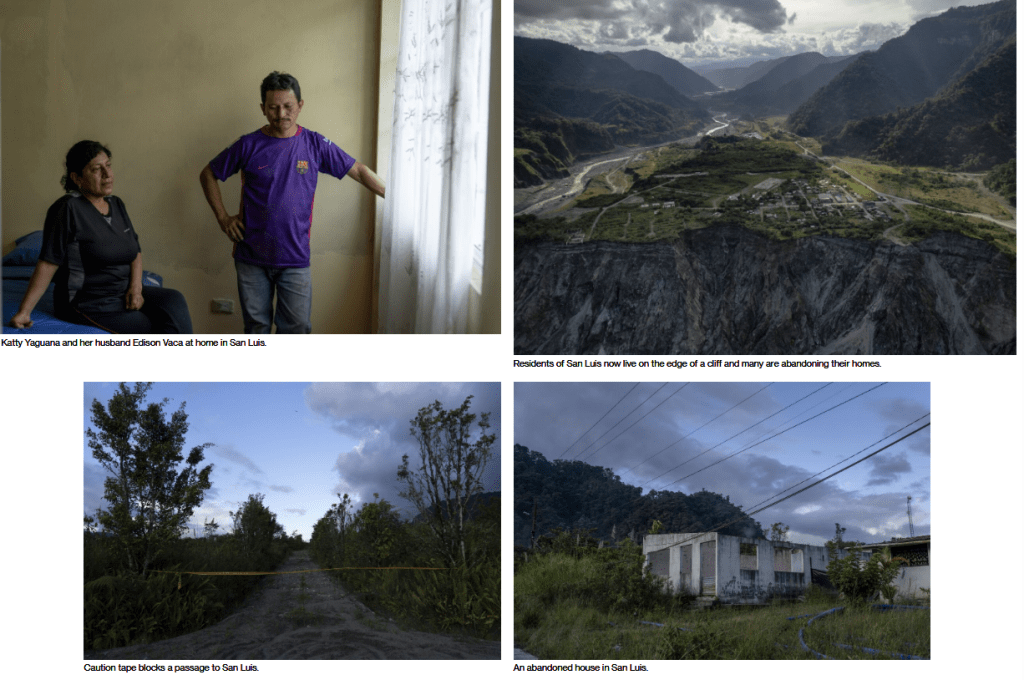

It also put the spiffy residential complex with a pool and roofed basketball court — built by Cahuatijo, the local civil engineer — at the edge of a cliff.

It was immediately evacuated and condemned. These days there is a single security guard on site to keep people out. The shifting landscape and tropical climate are leaving it a decayed mess. The main gate is leaning forward and is propped by a log.

“I made all of this,” Cahuatijo said, shaking his head. “The budget certainly could have been dedicated to other things, but we didn’t know what would happen.”

The scientists and engineers consulted by Bloomberg are split on whether the waterfall collapse was caused by Coca Codo Sinclair or merely coincidental. What almost everyone agrees on is that planners should have taken the geologically fragile waterfall into consideration.

“It’s a case study in how not to do things”

“It’s a case study in how not to do things,” said Emilio Cobo, an expert in freshwater ecosystems who previously worked an adviser to Ecuador’s Ministry of the Environment. “They underestimated the sediment. They never did studies on the San Rafael waterfall.”

Sinohydro has released social media posts asserting that the project didn’t have an impact on the waterfall collapse. Sinohydro, Celec and the ministry of energy and mines didn’t respond to requests for comment.

The residents Bloomberg spoke to in the river towns are all convinced that the project is to blame. One of them is Katty Yaguana, 52, who moved to a hamlet known as San Luis in 2008. She was suffering economic hardship in Quito and had heard that a pipeline spill had opened up opportunities to work on cleanup crews.

Read More: The World’s Biggest Source of Clean Energy Is Evaporating Fast

That didn’t pan out, but she and her husband found jobs at the residential complex that Cahuatijo was building. Little by little, they built a two-story cinder block home in San Luis — which is now turning into a ghost town. Four homes have slid off the cliff due to erosion from the waterfall collapse. Authorities have said residents can’t do any major repair works on their homes and have said they will be relocated. About half the homes are abandoned. Cobo thinks San Luis will be completely gone within five years.

“I regret investing so much and all for nothing. We should have gone to a less dangerous place,” said Yaguana. “People are leaving because they’re afraid of the volcano and the landslides. I’d leave if I had a place to go.”

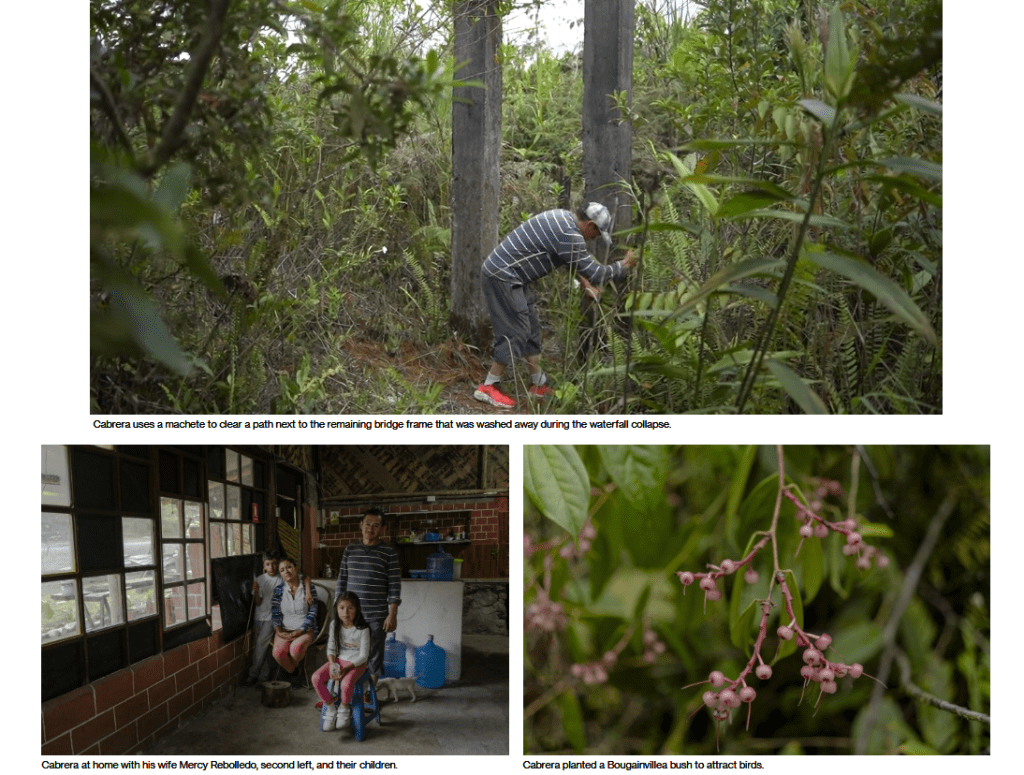

Jairo Cabrera lives just a few miles down the road from San Luis and is organizing residents who lost land from the regressive erosion, a process that spreads up a river valley and often causes slope failures. He wants state-owned utility Celec, which hired Sinohydro, to pay compensation.

“They caused all this regressive erosion,” he says, clearly agitated. “Some of us have been able to get work with what’s left. Others have lost everything.”

Cabrera had an ecotourism business with four cabins and a nearly two-mile nature trail leading up to the waterfall. Slim and athletic at 47, he walks across what’s left of his property, swinging a machete to clear the now-abandoned nature path. He points out a flowering Bougainvillea bush that he planted to attract birds.

All that’s left is a concrete frame that was once part of metal bridge that took tourists across the river. The rest was washed away with the waterfall. Standing at the edge of a huge canyon that plunges nearly a thousand feet, he points and says “that’s where the river used to be.”

Down below, a fleet of nearly 50 dump trucks is busy hauling dirt and loose sediment from a section of the river where Celec hired a consortium to build a $17.3 million permeable dike and drill concrete pillars into the riverbed. Erosion has already made it past the site, which means the riverbed has already lost part of the ground that needs to be protected.

Leonardo Baez has been working to protect roads and the riverbed from regressive erosion since 2020 as a project manager at Accyem Proyectos, a civil construction company that is part of the consortium. He fears that the existing project, which will take until late 2025 to complete, isn’t sufficient.

“The problem with regressive erosion is that it’s a phenomenon that doesn’t have a defined behavior,” said Baez. “When the river floods, it advances exponentially.”

The current project only protects against 33 feet of erosion, which won’t be enough if the river subsides more than expected, he said. Accyem is proposing a novel engineering solution to protect the dike from at least 60 feet of erosion — an anti-sinkhole blanket.

The idea is to cover the riverbed underneath the dike with an enormous structure of flexible steel with separate compartments that are filled with boulders or weighted containers. When the ground subsides, it would bend and adjust instead of breaking, and prevent the erosion from reaching the dike.

“With the flexible anti-sinkhole blanket, we think we can protect the structure,” he said. “If not, it could collapse.”

Accyem continues to lobby Celec to incorporate the novel technology, he said.

Even if Ecuador manages to keep Coca Codo Sinclair up and running, it could wind up costing hundreds of millions of dollars in constant remediation work that should be getting invested into alternative sources of energy such as large scale solar parks, said Cobo, the expert in freshwater ecosystems.

But what he sees is Ecuador making the same mistakes at other sites, such as the Santiago hydroelectric project it plans to build in the southeast. It’s meant to produce more than twice as much as Coca Codo Sinclair and come on line in the early 2030s.

Again, planners aren’t taking into account how silty the river is, which has only been made worse by illegal mining in the area.

“I don’t know what they are going to do with all that sediment,” he said.

Edited by Simon Casey, Danielle Balbi and Doug Alexander

Photo edited by Marie Monteleone

Bloomberg.com 01 09 2025