By Javier Blass/Bloomberg

Inside NATO headquarters in Brussels, senior officials gathered last week to think the unthinkable: What would happen to Europe if Russia — by far its largest supplier — cuts off the flow of natural gas westward?

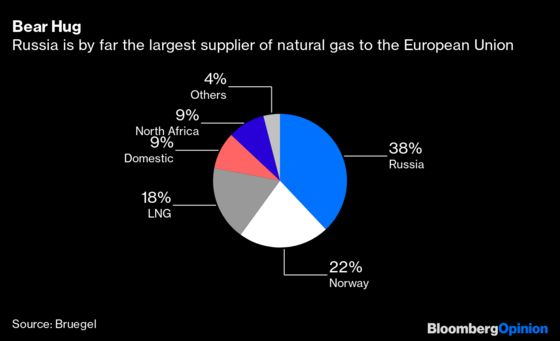

Every day, Europe buys almost 40% of the gas it consumes from Gazprom, the Russian-state owned giant. In 1968, Austria became the first Western European country to sign a contract to buy Russian gas. Since then, the trade has withstood political and economic upheavals, including the depths of the Cold War and the collapse of the Soviet Union.

At least, until now. The threat of military conflict in Ukraine has turned natural gas into a weapon of mass disruption.

Already, Russian gas flows into Europe are sharply lower than in the past, at times about 30% below the five-year average. Gazprom insists it’s fulfilling long-term contracts with European utilities. Indeed, last year Gazprom made 1.8 trillion rubles ($23.2 billion) from its sales to Europe — that is about 10% of all Russia’s exports, according to the International Monetary Fund. But the company is sidestepping another truth. This is less about money — Moscow makes more money from petroleum — than about geopolitical squeeze plays. In a departure from tradition, Gazprom hasn’t filled up its European storage sites. Neither is it selling extra gas on the spot market. Europe is running on fumes: Gas inventories have dropped to less than 40% of capacity, the lowest ever for this time of the year. European has only avoided a gas crunch thanks to unusually mild weather so far this winter.

There are two main scenarios: the first is contained; the second, catastrophic.

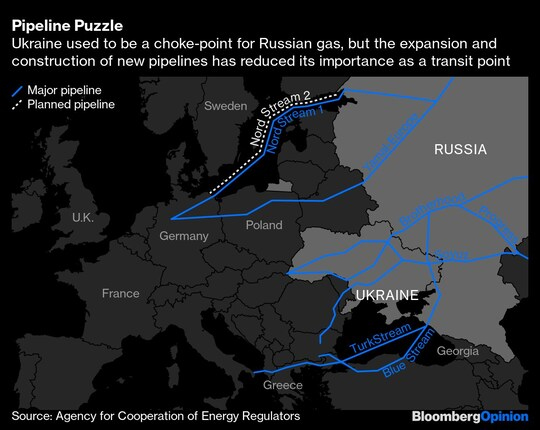

If Russia invades Ukraine, gas will be snarled by military action one way or another — perhaps even by accident as pipelines and other pieces of infrastructure are hit. But if the campaign is swift and Moscow’s objectives met quickly, Europe may be able to withstand even physical damage to pipelines in Ukraine. One need only look at a map to see why: The Russian flows have changed over the last two decades.

Well into the 1990s, Ukraine was the chokepoint of nearly all Russian gas into Europe via the Soyuz, Brotherhood and Progress pipelines. Since then, Russia has diversified transit with the Yamal-Europe, Nord Stream 1, Blue Stream and TurkStream. And that’s before the addition — pending regulatory approval — of Nord Stream 2. The new routes have reduced the significance of Ukraine — something many politicians have failed to understand. Memories in Western Europe of the 2006 and 2009 Ukraine-Europe gas crises, when supplies were disrupted, still shape the understanding of the market. But in gas, 2022 isn’t 2009 by a long margin.Two decades ago, Ukraine was the transit point for about 125 billion cubic meters of Russian gas into the rest of Europe. Last year, the flow had plunged 65% to less than 42 bcm. That’s still a significant amount, but not nearly as much as in the past. Perhaps as importantly, Ukraine is no longer a key transit point for Russian gas into Germany and another half-dozen countries. Today, it’s important for just Slovakia, Austria and Italy. Nikos Tsafos, a gas expert at the Center for Strategic and International Studies in Washington, puts it succinctly: Ukraine “used to be the main corridor for delivering Russian gas to Europe; it is no longer that.”

Europe is in a far better shape today to respond to a crisis if only gas passing through Ukraine is involved. For a limited period, Europe could cope with a shutdown of Ukraine-transit gas through a combination of higher LNG imports, and further withdrawals of the commodity from storage. If the weather remains mild, demand would be even lower.

Of the three countries at biggest risk, Italy can import LNG directly, and its gas inventories are high, in part because Rome has a strategic gas storage that the rest of the continent largely lacks. As of Monday, Italian storage was at 50.8% of capacity, significantly higher than the European average of 38.9%. Austria and Slovakia are however in far worse shape (their inventories stand at 22.7% and 32.5%, respectively), and would require significant help from their neighbors.

All this assumes Moscow would re-direct supplies away from Ukraine using other pipelines — and continue to send gas to Europe. A continent-wide total shutdown is a completely different matter.

When European regulators war-gamed potential gas disruptions in November, they analyzed 19 scenarios, with several permutations for each. But they didn’t contemplate what would happen if all Russian flows ceased. Why? Because it isn’t pretty, and, effectively, there aren’t workarounds. If that happens, there’s simply no way the continent would be able to avoid unimaginable economic pain and blackouts.

As much as U.S. and European diplomats say they’re scouting the world for extra gas supplies, there isn’t enough available elsewhere to replace Russia. On the margins, Qatar and a couple of other LNG exporters may be able to help. LNG prices would rise so much that some Asian developing countries like Pakistan and Bangladesh would be priced out of the market, freeing extra cargoes to Europe (at the cost of blackouts in Asia). At best, Europe can hope to replace two-thirds of Russian supplies. That estimate may be generous.Europe would also face an additional challenge. It’s one thing is to attract LNG cargos to its shores; another, and far more difficult, is to actually funnel that gas into the continent-wide distribution system. Nearly a third of European LNG regasification capacity is located in Spain, which has only a tiny pipeline connecting it with the rest of the continent. Add France and the U.K. to Spain, and that’s 70% of all European regasification capacity. Germany doesn’t have a single regasification plant.

The only recourse would be rationing — first with basic services like hospitals and residential heating, then electricity production, which would try to rely on coal and oil. After that, all the gas would run out and, eventually, all industries would have to shut down.

The economic pain would be tremendous, and would test European solidarity. “There is a risk that countries with better supply situations might be unwilling to share scarce gas resources with countries that are in an even worse situation,” argues Simone Tagliapietra at the Brussels-based think tank Bruegel. He’s right: As the Covid-19 crisis showed, countries may put national interest before regional one.

In the full-shut down, gas prices will skyrocket, making the record-high seen in December look piddling. Indeed, the surges may be fivefold, perhaps even tenfold. Europe doesn’t want that but will Vladimir Putin do it?

I have my doubts. The Russian President would prefer Europe remain tied economically to Russian gas forever. For Moscow, control of the spigots equals geopolitical influence in Europe; the ability to halt it serves the Kremlin better as threat than as reality. In many ways, it plays the same role as nuclear weapons in conventional warfare: mutual assured destruction or MAD. If Russia chose to use gas as a weapon, Europe would move heaven and earth in the next few years to never again rely on Gazprom for a single gas molecule. That’s why Putin is only slightly weaponizing gas — restricting supplies, rather than cutting them off.

That’s his leverage. If he goes apocalyptic, Russia’s own future would be at risk. It’s a weapon that works only by never using it.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He previously was commodities editor at the Financial Times and is the coauthor of “The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources.”

bloomberg.com 02 01 2022