There’s an opportunity to close budget gaps, reduce petroleum demand and cut emissions, all at once. The answer lies in public transit.

By David Fickling | Bloomberg

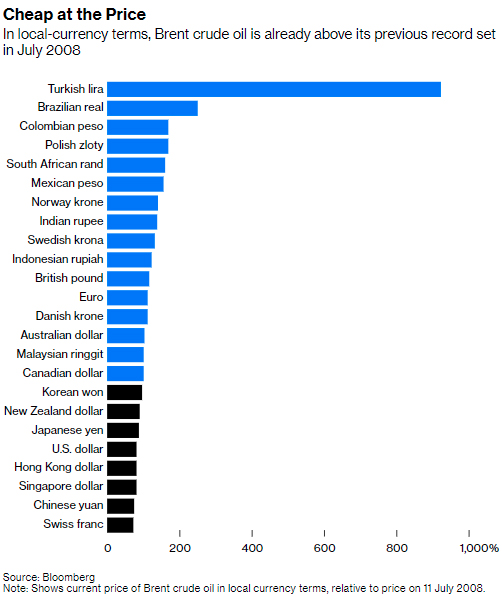

You don’t need to look at how close crude is getting to its all-time record high of $147.50 a barrel to know what a world struggling with elevated oil prices looks like. For most of humanity, we’re already there.

In nominal local-currency terms, countries accounting for at least a third of global oil consumption are already paying more than they ever had. Members of the euro zone and India, the largest consumers of crude after the U.S. and China, surpassed their previous record prices on Wednesday and Monday, respectively. Brazil, Mexico and Indonesia are all in the same boat:

With the Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries promising only a modest increase in crude supplies next month and an unknown but possibly large slice of Russia’s 11 million daily barrels a day coming off the market as economic sanctions start to bite, the prospect of demand destruction starts rising. That’s a fancy term for what, to most of us, will look like a recession.

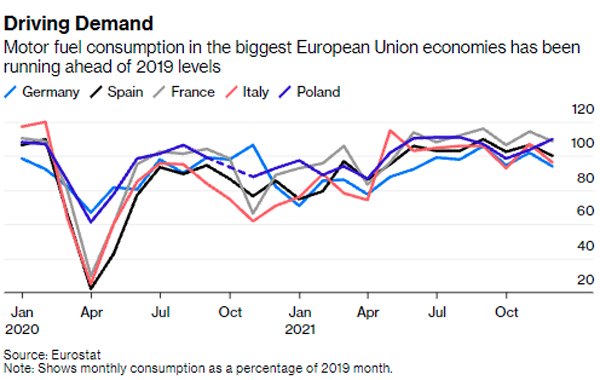

Oil itself usually suffers last from energy price shocks, because households and businesses have no choice but to spend money filling up their cars, or buying cooking gas, or running generators. Instead, consumers will cut back on discretionary spending and businesses will limit investments. That situation worsen if inflation gets bad enough that central banks start to raise rates.

Governments aren’t quite as powerless in the face of this as they may seem, however. Indeed, if they move rapidly, there’s an opportunity to close budget gaps, reduce petroleum demand, and cut emissions, all at once. The answer lies in public transit.Sponsored ContentJapan – Home to Over 10,000 Future-Shaping Start-upsJapanGov

Retail fuel prices are rarely all that close to the price of gasoline and diesel coming out of a refinery. Across Europe and the wealthier Asian nations, taxes mean transport fuel typically costs close to double what it does in the U.S. That mutes the effect of price rises.

Elsewhere, the fiscal thumb is on the other side of the scale. Most oil exporters and many emerging economies subsidize their dirtiest sources of energy. Direct subsidies for fossil fuels amounted to $760 billion in 2018, according to a study last year by the International Monetary Fund. That will probably be considerably higher this year, since the subsidy bill rises along with oil and gas prices. 1

Already last year, elevated crude prices have pushed some emerging-market governments to reconsider reforms carried out when prices were lower after the 2014 commodities crash. In India, the government of Prime Minister Narendra Modi took the opportunity of the collapse in crude prices that same year to add excise duties, which now make up nearly a quarter of the government budget — but last November it cut those levies and urged state governments to cut sales taxes too to ease pressure on road users.

There’s a similar situation in Brazil. Since 2016, government-controlled Petroleo Brasileiro SA, with a near-monopoly on local production, has set prices based on the cost of crude in the global market. That’s often been a source of tension with the government, given the effect of a weakening local currency on locally priced oil. Former President Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, who’s challenging incumbent Jair Bolsonaro in the election due later this year, has called for the government to act to lower costs. Congress is considering legislation that would have the same effect.

At these crude prices, that policy could be costly. In Indonesia, one of the few large emerging oil importers to heavily subsidize retail prices, the government last week took the opposite tack, saying it’s likely to let costs rise because of concerns that the current situation would lead to either too great a drain on the budget or cause state-owned Pertamina Persero PT to collapse.Sponsored ContentElectrifying Last Mile Deliveries Can Create a More Sustainable Supply ChainGM

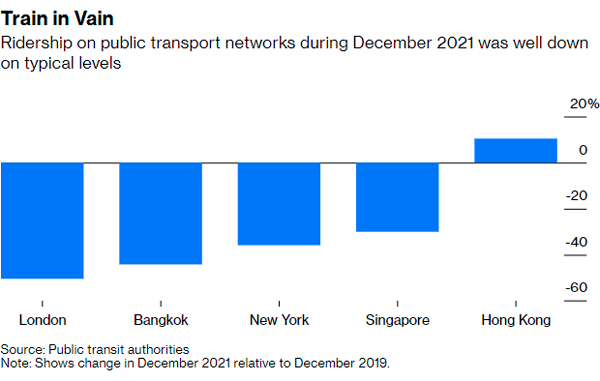

There’s a better solution out there. In most of the world, public transport networks are still well down on typical ridership levels, two years into the Covid-19 pandemic. That risks creating a vicious circle, where low patronage cuts revenues, driving service cuts which in turn reduce patronage.

Central governments are typically reluctant to get too involved in this, especially as urban transport is often run by politically opposed local officials. Weeks after announcing a 9.1 billion pound ($12.2 billion) annual package to reduce household energy bills, the U.K. government last month offered 200 million pounds to keep London’s transport network from bankruptcy for four months.

That’s a mistake. With oil prices at these levels, governments are already looking at using their budgets to ease cost-of-living pressures on households. Encouraging citizens back onto under-utilized public transit would be a far better use of subsidy funds than stoking demand for oil in the middle of a supply crisis.

_________________________________________

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on March 03, 2022. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

bloomberg.com 03 03 2022