Lower prices for oil later this year and into 2023 reflect expectations of diminished demand, increased production

(Yohap News)

Ryan Dezember and Kenny Jimenez, WSJ

NEW YORK

EnergiesNet.com 03 07 2022

Oil buyers have been paying the biggest premiums on record for barrels delivered now rather than later, signaling expectations that high fuel prices will reduce consumption and encourage drilling to replace Russia’s taboo crude.

Prices for April deliveries of crude have shot up since Russia invaded Ukraine and buyers began shunning the aggressor’s oil exports. The main U.S. price last week topped $110 a barrel for the first time in more than a decade.

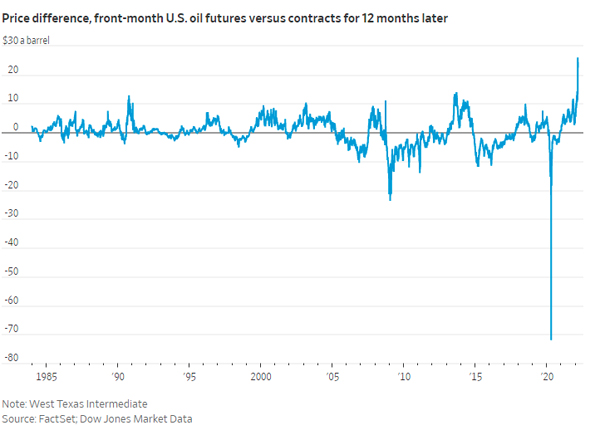

Futures contracts for delivery in subsequent months have risen as well, but not by nearly as much. When U.S. futures for delivery next month ended Wednesday at $110.60 a barrel, contracts for next March settled at $84.53. The $26.07 difference has never been greater in favor of the front month.

Prices ended the week a little closer together, yet the spread remains historically wide.

The pattern is mirrored in international markets, where the 12-month price spread on benchmark Brent crude futures also surpassed $20 a barrel last week for the first time on record.

“It’s hoarding,” said RBC Capital Markets analyst Michael Tran. He points to an 83% week-over-week jump in lease rates for very large crude carriers on the Persian Gulf to Asia route as further evidence that buyers are paying whatever they must to stock up in case Russian exports dry up. “People are saying, ‘Give me as much as you’ve got, I’ll buy as much as I can,’” he said.

Over nearly four decades of trading in West Texas Intermediate futures, a barrel on average has cost 40 cents more than one delivered a year later. The difference rarely exceeds $10 in either direction, and when it does, the blowout is usually related to a war, hurricane, market crash or pandemic.

The widest spread on record came in April 2020, when the global economy was locking down to slow the spread of Covid-19 and front-month U.S. oil-futures prices plunged into negative territory. The worry was that fuel consumption was falling faster than oil producers could shut off the spigots, leading to trades in which sellers effectively paid buyers to take oil off their hands. Prompt-month futures settled at negative $37.63 after one historic trading session, while contracts for barrels one year out stayed above water at $34.35, for a spread of negative $71.98.

Producers eventually choked back before the world’s oil storage facilities overflowed. Now as economies reopen, producers—from the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries to Texas frackers—have been slow to meet rising demand. The imbalance has drained fuel stockpiles around the world and sparked forecasts on Wall Street for $100 oil this summer, during peak driving season.

Triple-digit oil prices arrived sooner than expected when Russian tanks rolled into Ukraine. Analysts and Wall Street strategists are upping their price forecasts even higher now that Russia’s oil exports are being treated as off-limits by many buyers.

OPEC and its market allies, including Russia, have chosen to maintain the cartel’s production quotas despite surging prices.

U.S. oil output has remained flat since autumn at around 11.6 million barrels a day, yet there are signs that free-market producers are ramping up to capture higher prices. There were 519 rigs drilling in the U.S. for crude last week, up from 480 at the start of the year, when oil was $76 a barrel, according to oil-field-services firm Baker Hughes Co.

Allowing for time to permit and drill wells, it could be six to nine months before increased domestic drilling, even with government incentives, adds meaningful supply, Jefferies analysts estimate. Until then—and barring diplomatic deals that would allow more oil to flow from erstwhile petro powers Venezuela and Iran—analysts say prices are likely to rise until consumers can no longer bear the expense and reduce consumption.

“Should the market remain averse to Russian barrels for a sustained period of time, we’re hard pressed to see a scenario in which prices don’t test for pressure points on demand destruction into the $120s, $130s or higher,” analysts with Houston investment bank Tudor, Pickering, Holt & Co. wrote in a note to clients.

The average retail price of gasoline in the U.S. ended February at $3.608 a gallon, up 28% from a year earlier. Gasoline futures have risen 20% so far in March, foreshadowing more pain at the pump for Americans already grappling with inflation across their household budgets.

Here’s how rising oil costs could further boost inflation across the U.S. economy. (Photo illustration: Todd Johnson)

GasBuddy, which collects fuel prices from consumers, service stations and fuel-card transactions in real time, on Thursday said it expects gasoline to average $3.99 a gallon this year across the U.S., up from a prediction of $3.41 before the Ukraine invasion.

Patrick De Haan, GasBuddy’s lead petroleum analyst, said that the record average price of about $4.10, set when crude shot up to nearly $150 a barrel during 2008’s financial-market meltdown, would be about $5.25 today adjusted for inflation. It will probably take higher prices than that to alter American driving habits enough to really dent demand, given how flush consumers are and how retail spending has continued to rise despite broad inflation, Mr. De Haan said.

“I don’t know that they will slow down this year,” he said. “The economy is ripe for motorists to discount what we’re seeing at the pump.”

Write to Ryan Dezember at ryan.dezember@wsj.com

wsj.com 03 06 2022