Jonathan Gilbert, Bloomberg News

BUENOS AIRES

EnergiesNet.com 07 08 2022

A sudden change of economy minister in Argentina that gives the leftist faction of the ruling coalition a grip on the country’s finances poses a risk to a key part of its International Monetary Fund agreement — weaning the population off energy subsidies.

Silvina Batakis was sworn in this week after Martin Guzman, an economic moderate who negotiated the IMF deal earlier this year, resigned in part because government officials appointed by Vice President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner blocked him from implementing energy policy as he wished. Batakis is an ally of Kirchner, a long-time antagonist of global markets and the IMF.

To be sure, Batakis said in a radio interview Tuesday that she’d push ahead with reducing energy subsidies as she tries to calm investors whose gut reaction to her arrival was to sell Argentine assets. Argentina’s bonds continued falling on Wednesday, with benchmark sovereign notes slipping 0.4 cent on the dollar in early trading to around 20 cents.

Several analysts insisted that a question mark hangs over Batakis’s commitment to the spending cuts penned by Guzman and the IMF. In the same interview, she warned that some targets under the IMF program would have to change. This year, the program aims to trim energy subsidies by 0.6% of gross domestic product.

“There’ll be less willingness to follow through with subsidy cuts, which will probably stop them from becoming the fiscal anchor that Guzman wanted,” said Lucas Caldi, a credit analyst at Portfolio Personal Inversiones in Buenos Aires.

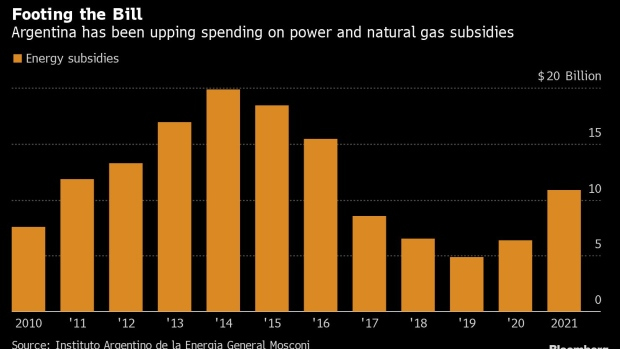

Billions of dollars a year in power and natural gas subsidies are one of the drivers of Argentina’s fiscal deficit, leading to loose monetary policy and imbalances like inflation. But reducing them is a delicate dance for a coalition that’s in power thanks largely to voters seeking a return to the generous welfare state of the 2003-2015 era, when Kirchner and her late husband governed.

Guzman oversaw hikes to energy bills this year and last after prices had been frozen for two years. But he was struggling to win support from Kirchner loyalists for more increases. When consumers pay more, the government pays less. In addition, Argentina is yet to implement a so-called “segmentation,” a politically-sensitive policy that’d see payments to some middle-class families scaled back.

“Guzman defended segmentation tooth and nail, but now an uncertainty arises,” Caldi said.

Government energy spending has been soaring recently as Argentina imports expensive fuel cargoes to meet winter demand. Subsidies for the 12 months through June were $13.5 billion, way up from the more than $7 billion in the previous 12-month period, said Julian Rojo, an analyst at the General Mosconi think tank in Buenos Aires. In May, consumers paid just 36% of the cost of producing power, which accounts for most of the subsidies, down from 42% in March and 39% in April, according to Portfolio.

Spending could grow further if Batakis opts to devalue the peso but shields voters already grappling with 61% inflation by applying slow — or no — increases to energy bills. That’s because much of Argentina’s energy production pricing is linked to the dollar. The difference between the official, controlled foreign exchange rate and weaker market rates is widening, a trend that often augurs a devaluation.

“The gap in the exchange rates that’s opening up is unacceptable,” making a devaluation likely, said Nicolas Gadano, an Argentine consultant and university professor who specializes in the intersection of economics and energy. “That could produce a situation where consumers cover even less of the price of energy.”

Still, investors will have to wait to see Batakis’s true colors. “Batakis is a relatively recent convert to Kirchnerismo and was more of a ‘rational heterodox’ in the past,” Nicholas Watson, a Latin America analyst for Teneo, wrote in a note. “Just how rational and how heterodox she is now will become clear in the coming week.”

bloomberg.com 07 06 2022