By David Wainer

The International Monetary Fund and Argentina are like a terminally unhappy couple trying to repair a broken marriage. No matter how often they decide to give it another shot, the end result is always the same: broken promises and a resurfacing of old disputes.

The two sides are once again tentatively moving toward an agreement, the 22nd in their history.

The pact, which still needs approval by the country’s congress and the IMF’s board of directors, would refinance more than $40 billion of outstanding debt stemming from the lender’s record 2018 bailout. In exchange, Argentina would gradually reduce its fiscal deficit and tighten its monetary policy to combat inflation.More fromBloombergOpinionBritain Just Delivered a Crushing Blow to the PressIntel’s Gelsinger Is Spending Shareholder Money for Lofty GoalsThe Olympics Have Been a Raging Success — for ChinaAmericans Shrug Off Inflation With Some Retail Therapy

The initial understanding gives Argentina some breathing room. But it doesn’t pave the way for the changes its economy needs, much less improve Argentina’s long-term ability to pay back its debt. If the administration of President Alberto Fernandez doesn’t lay out a clearer plan to incentivize private sector investment, diversify away from agriculture and expand its tax base, Argentina is doomed to default on its debt later this decade.

While the two sides haggled over economics, the deeper problem is political. The IMF recognizes it made mistakes when it extended $57 billion to bolster Mauricio Macri’s government in 2018. Much of the money was wasted in a failed attempt to prop up the peso, leaving Argentina with a bloated debt burden and little to show for it.

There was only so much the IMF could ask from Fernandez’s Peronist government, whose political base loathes the institution. Domestic political divisiveness, known in Argentina as “la grieta,” meant Fernandez lacked the political capital to deliver on tougher measures. Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the IMF, acknowledged the low expectations when she told the press the fund had to recognize “the limitations of what can be done over the next years.”

Indeed, Argentina limps from crisis to crisis mainly because its political dysfunction means governments can’t stick to durable economic platforms to win back investor trust.

“Financial markets don’t believe in Argentina,’’ says Miguel Kiguel, a former undersecretary of finance in Argentina.

The political dysfunction was apparent immediately after the IMF and Argentina thrashed out a deal. Lawmaker Máximo Kirchner, son of the powerful Vice President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner and leader of the governing Frente de Todos caucus in the lower house, resigned in protest. His mother, a former president, has taken a harsh stance toward IMF policy prescriptions. Argentina’s opposition, which now makes up the largest bloc in congress, has signaled support for the deal and scored political points by criticizing the governing coalition’s disunity.

Facing a pile of debt coming due this year, the IMF and Argentina, led in talks by U.S.-trained economist Martin Guzman, opted to muddle through for now.

The agreement’s goals aren’t bad. The pact does call for positive real interest rates — sorely needed to address inflation that is above 50% — and for the government to balance its primary fiscal deficit, a necessary step in order to reduce its high debt-to-GDP ratio of about 100%. The IMF also signaled it expects Argentina to reduce energy subsidies.

But the agreement, whose details haven’t yet been made public, doesn’t lay out a firm way of getting there. The Finance Ministry’s insistence that no spending cuts are planned raises questions about how the deficit can be reduced. While boosting tax collection could bring it down, a sudden decline in commodity prices, for instance, would make it hard for the country to honor its commitments. And to stick to spending cuts just ahead of presidential elections in 2023 will be a tall ask.

“At best, we will see a tentative shift in the direction of market-friendly policies,’’ said Nikhil Sanghani, an emerging markets economist specializing in Latin America at London-based Capital Economics.Opinion. Data. More Data.Get the most important Bloomberg Opinion pieces in one email.EmailSign UpBloomberg may send me offers and promotions.By submitting my information, I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

Another major question is how Argentina plans to increase its fast-dwindling foreign currency reserves to a proposed $5 billion. The deal doesn’t ask Argentina to devalue its currency sharply, which typically boosts a nation’s current account by making exports cheaper and imports less desirable. Argentina’s capital controls have led to flourishing black markets in the streets of Buenos Aires, where a dollar costs around double the official rate. Guzman insists there will be no “jump” in the exchange rate. Argentina understandably worries a large devaluation could lead to runaway inflation, as it did under Macri. But too much gradualism will stand in the way of a faster recovery.

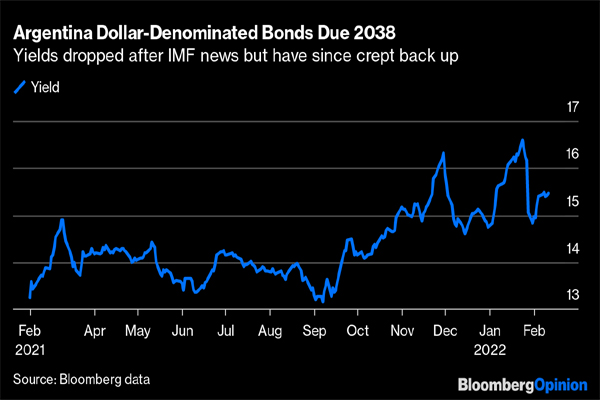

The bitter truth is that unless a true economic miracle takes place (not Joseph Stiglitz’s much-criticized version of a miracle), Argentina will struggle to pay back lenders. Argentine bond yields reflect such pessimism. While yields on bonds due 2038 dropped from a high of 16.6% after the deal was announced, they have since crept back up to 15.5%.

The International Monetary Fund and Argentina are like a terminally unhappy couple trying to repair a broken marriage. No matter how often they decide to give it another shot, the end result is always the same: broken promises and a resurfacing of old disputes.

The two sides are once again tentatively moving toward an agreement, the 22nd in their history.

The pact, which still needs approval by the country’s congress and the IMF’s board of directors, would refinance more than $40 billion of outstanding debt stemming from the lender’s record 2018 bailout. In exchange, Argentina would gradually reduce its fiscal deficit and tighten its monetary policy to combat inflation.More fromBloombergOpinionBritain Just Delivered a Crushing Blow to the PressIntel’s Gelsinger Is Spending Shareholder Money for Lofty GoalsThe Olympics Have Been a Raging Success — for ChinaAmericans Shrug Off Inflation With Some Retail Therapy

The initial understanding gives Argentina some breathing room. But it doesn’t pave the way for the changes its economy needs, much less improve Argentina’s long-term ability to pay back its debt. If the administration of President Alberto Fernandez doesn’t lay out a clearer plan to incentivize private sector investment, diversify away from agriculture and expand its tax base, Argentina is doomed to default on its debt later this decade.

While the two sides haggled over economics, the deeper problem is political. The IMF recognizes it made mistakes when it extended $57 billion to bolster Mauricio Macri’s government in 2018. Much of the money was wasted in a failed attempt to prop up the peso, leaving Argentina with a bloated debt burden and little to show for it.

There was only so much the IMF could ask from Fernandez’s Peronist government, whose political base loathes the institution. Domestic political divisiveness, known in Argentina as “la grieta,” meant Fernandez lacked the political capital to deliver on tougher measures. Kristalina Georgieva, managing director of the IMF, acknowledged the low expectations when she told the press the fund had to recognize “the limitations of what can be done over the next years.”

Indeed, Argentina limps from crisis to crisis mainly because its political dysfunction means governments can’t stick to durable economic platforms to win back investor trust.

“Financial markets don’t believe in Argentina,’’ says Miguel Kiguel, a former undersecretary of finance in Argentina.

The political dysfunction was apparent immediately after the IMF and Argentina thrashed out a deal. Lawmaker Máximo Kirchner, son of the powerful Vice President Cristina Fernandez de Kirchner and leader of the governing Frente de Todos caucus in the lower house, resigned in protest. His mother, a former president, has taken a harsh stance toward IMF policy prescriptions. Argentina’s opposition, which now makes up the largest bloc in congress, has signaled support for the deal and scored political points by criticizing the governing coalition’s disunity.

Facing a pile of debt coming due this year, the IMF and Argentina, led in talks by U.S.-trained economist Martin Guzman, opted to muddle through for now.

The agreement’s goals aren’t bad. The pact does call for positive real interest rates — sorely needed to address inflation that is above 50% — and for the government to balance its primary fiscal deficit, a necessary step in order to reduce its high debt-to-GDP ratio of about 100%. The IMF also signaled it expects Argentina to reduce energy subsidies.

But the agreement, whose details haven’t yet been made public, doesn’t lay out a firm way of getting there. The Finance Ministry’s insistence that no spending cuts are planned raises questions about how the deficit can be reduced. While boosting tax collection could bring it down, a sudden decline in commodity prices, for instance, would make it hard for the country to honor its commitments. And to stick to spending cuts just ahead of presidential elections in 2023 will be a tall ask.

“At best, we will see a tentative shift in the direction of market-friendly policies,’’ said Nikhil Sanghani, an emerging markets economist specializing in Latin America at London-based Capital Economics.Opinion. Data. More Data.Get the most important Bloomberg Opinion pieces in one email.EmailSign UpBloomberg may send me offers and promotions.By submitting my information, I agree to the Privacy Policy and Terms of Service.

Another major question is how Argentina plans to increase its fast-dwindling foreign currency reserves to a proposed $5 billion. The deal doesn’t ask Argentina to devalue its currency sharply, which typically boosts a nation’s current account by making exports cheaper and imports less desirable. Argentina’s capital controls have led to flourishing black markets in the streets of Buenos Aires, where a dollar costs around double the official rate. Guzman insists there will be no “jump” in the exchange rate. Argentina understandably worries a large devaluation could lead to runaway inflation, as it did under Macri. But too much gradualism will stand in the way of a faster recovery.

The bitter truth is that unless a true economic miracle takes place (not Joseph Stiglitz’s much-criticized version of a miracle), Argentina will struggle to pay back lenders. Argentine bond yields reflect such pessimism. While yields on bonds due 2038 dropped from a high of 16.6% after the deal was announced, they have since crept back up to 15.5%.

David Wainer is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering the business of entertainment and telecommunications. He has covered markets, health care, economics and international affairs for Bloomberg News. @david_wainer. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on February 16, 2022. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

energiesnet.com 02 16 2022