David Papadopoulos, Boomberg News

NEW YORK

EnergiesNet.com 05 20 2022

Hello. Today we look at what’s happening at Bloomberg’s New Economy Gateway conference, which countries are most at risk of stagflation and which football team the European Central Bank supports.

Nearshoring Test Case

A key component for being bullish on Latin America is based on near-shoring, the idea that multinationals will build more factories in the region to bring their output closer to its final destination in the US market.

The days of the span-the-globe supply chains died in the pandemic, the theory goes, and shorter is now inherently better.

On the first day of Bloomberg’s New Economy Gateway Latin America event in Panama, there were plenty of advocates of this axiom.

Perhaps none was more vocal than Mauricio Claver-Carone, the head of the Inter-American Development Bank.

He was talking his book at some level, of course, given his mandate to promote growth in the region and all, but he repeatedly spoke about concrete signs he was seeing of growing interest from multinationals in shifting output from Asia to Latin America.

“There’s not a day we don’t get calls,” Claver-Carone said.

It all makes perfect sense, especially after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine only further snarled corporate supply lines with long tails.

And Bloomberg News reporter Thomas Black recently found lots of evidence in border towns along the Mexican-US border that the shift had already begun: furniture makers, toy makers, medical device makers all carving out room in the desert for brand new factories.

The problem with all of this, though, as Marko Papic, a partner at Clocktower Group, sees it: There’s zero macroeconomic data that shows this migration in output is happening at any kind of meaningful level yet.

But perhaps both things can simultaneously be true: The shift from Asia to Latin America has commenced but just not in a meaningful enough way yet to start moving the needle. The question is whether Latin American leaders can seize the moment to make the trend last and help propel growth in a region that desperately needs it.

The Economic Scene

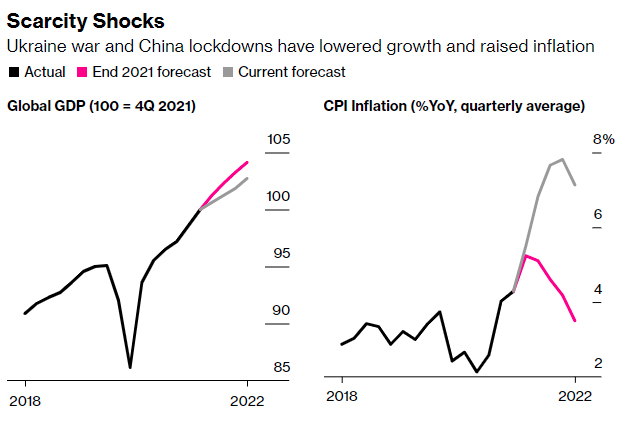

Note: PPP weighted quarterly data

The ties that bind the global economy together, and delivered goods in abundance across the world, are unravelling at a frightening pace.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and China’s Covid Zero lockdowns are disrupting supply chains, hammering growth and pushing inflation to forty-year highs. They’re the chief reasons why Bloomberg Economics has lopped $1.6 trillion off its forecast for global GDP in 2022.

While war and plague won’t last forever, the underlying problem — a world increasingly divided along geopolitical fault lines — only looks set to get worse, Maeva Cousin, Tom Orlik, and Bryce Baschuk write here.

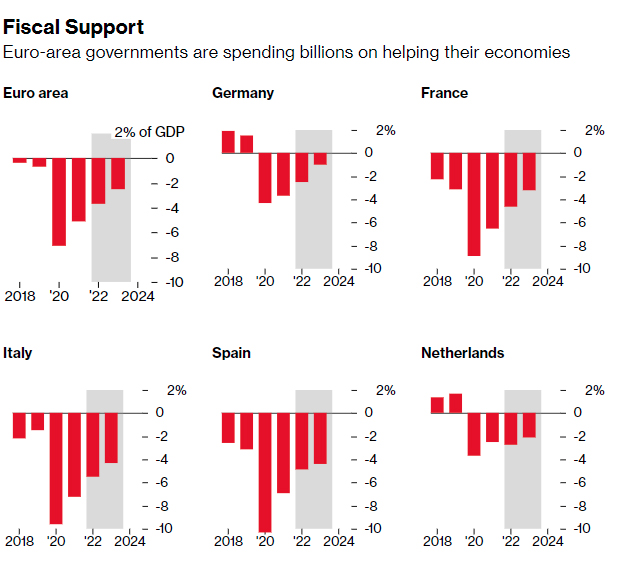

Note: 2021-2023 are estimates

Need-to-Know Research

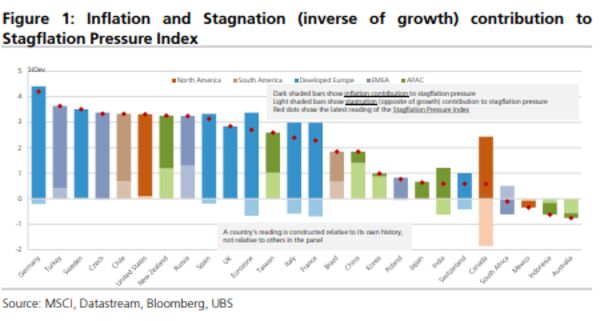

A new report from economists and strategists at UBS has a crack at quantifying which world economies are most at risk of stagflation.

It focuses on 45 economies and ten measures of growth and inflation, both real-time and forward-looking.

The results show Germany, the US, Sweden and the UK are experiencing the most elevated pressures along with Turkey and Russia, who have their own unique challenges.

There is better news for Australia, Canada, China, Mexico and India who are less troubled.

On the brighter side, the analysts say today’s stagflationary forces are less persistent than the 1970s.

The UBS model calculates it should take 29 months in the US and 20 months in Germany to halve the pressure. That compares with more than a decade in the 1970s.

On #EconTwitter

Something to cheer about.