- It has the world’s biggest reserves of a mineral crucial to reducing carbon emissions — and a history of commodity booms and busts that have failed to yield lasting economic development.

By Eduardo Porter

Just wait for the lithium to kick in. In a nutshell, that’s the message from President Luis Arce’s government to thousands of Bolivians worriedly evaluating their finances, waiting in interminable lines in hopes of getting some dollars before Bolivia’s balance of payments breaks and takes their bolivianos down with it.

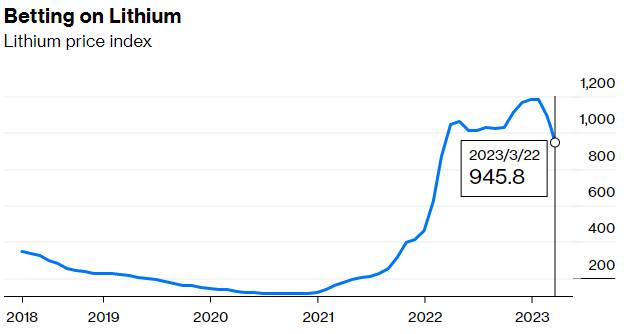

The claims from La Paz are not outright crazy. Bolivia has the world’s biggest lithium reserves. And the mineral has become invaluable for the transition to a carbon-free economy, which apparently will require lots of lithium ion batteries.

After letting the mineral deposits sit pretty much undisturbed for decades in its gargantuan salt flats — the state-owned lithium monopoly didn’t have the wherewithal to exploit them — the government just cut a $1 billion deal with Chinese companies that it hopes will ramp up commercial production and finally launch Bolivia’s economic development.

And yet, before Bolivians buy the government’s latest promise of prosperity, they will want to peer back over their shoulders at Bolivia’s recent past. No country offers a starker warning about the perils of betting on raw materials to fund a path out of poverty.

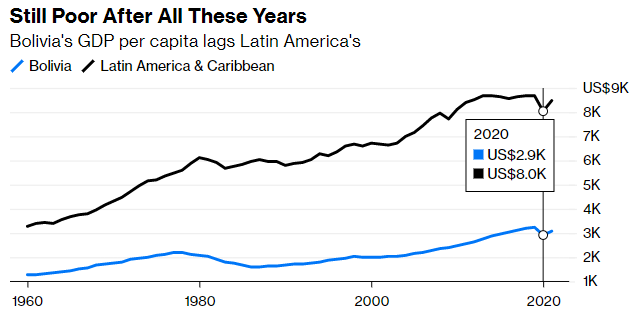

Bolivia has already experienced two massive commodity-fueled booms in the last 60 years or so, propelled by tin and gas exports — one in the 1960s and 1970s, another around the first decade and a half of the new millennium. Nonetheless, measured by gross domestic product per capita, it remains the poorest country in South America.

One hears that the “resource curse” isn’t really a thing. There are countries — Australia, Norway, Chile, even Botswana — standing against the blanket proposition that abundant natural resources inevitably condemn countries to poverty. Bolivia sits on the other side of this debate. It represents proof of concept that natural endowments can put economic development out of reach. The odds that it will do a better job of turning its lithium bounty into lasting riches look pretty long.

Bolivia’s booms have, as a rule, turned to bust. Between 1960 and 1977, its gross domestic product per person rose by 72%, after inflation. But it lost two-thirds of the gains in the following nine years, crushed by foreign debt accumulated on the upswing and a sharp rise in global interest rates.

Constant 2015 US$

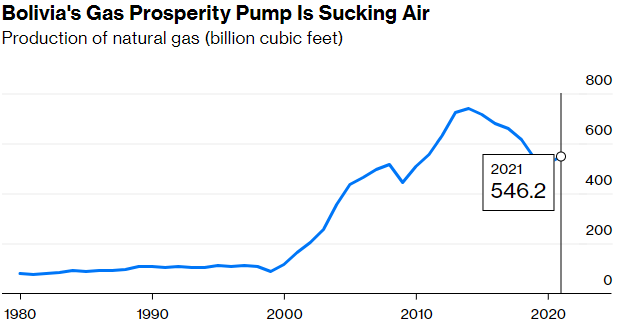

GDP per person surged again by more than half from 2002 through 2021. But dwindling gas reserves, mostly due to meager investment in exploration and development, and declining exports to Brazil and Argentina suggest that once again, boom may soon tip over into crisis.

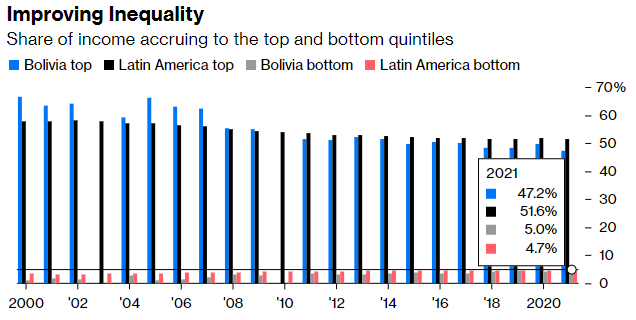

There is actually much to applaud about how Bolivia marshaled its natural gas bounty, spending it on combating poverty and mitigating inequality. Between 2002 and 2020, the share of Bolivians living on less than $2.15 a day dropped from almost one in five to just over 3%, one of the sharpest declines in Latin America.

“You can argue that in the first two decades of this century the two Latin American countries that changed the most in social and economic terms were Venezuela, for the worse, and Bolivia, for the better,” said Michael Shifter, former president of the Inter-American Dialogue now at Georgetown University’s Center for Latin American Studies. Unfortunately, its economic management has not kept up with its redistribution strategy.

As economists Timothy Kehoe, Carlos Gustavo Machicado and Jose Peres-Cajias noted in a study of the Bolivian economy, “government policies since 2006 are reminiscent of the policies of the 1970s that led to the debt crisis.” That experience, they wrote, raises again an uncomfortable question: “Is the Bolivian economy heading toward a balance of payments crisis?”

Booms fueled by metals, minerals or hydrocarbons are pretty much always narrow, limited to industries attached to the resource. “There is little evidence the booms have left behind the anticipated productivity transformation in the domestic economies,” noted Andrew Warner, an economist at the International Monetary Fund. Policies deployed by exporters of these resources have generally proven “insufficient to spur lasting development outside resource intensive sectors.”

Somehow, the government in La Paz has forgotten the painful recent history of how these booms end.

Economists debate the dynamics underlying the resource curse. Price volatility complicates macroeconomic management in poor countries that rely on commodities, encouraging procyclical fiscal and monetary policies that accentuate booms and busts. Commodity exports, moreover, drive up the exchange rate, handicapping the manufacturing sector. Natural resource bounties often breed corruption and weaken governance.

Bolivia’s case underscores how commodity booms distort the economy by promoting unproductive policies, allowing governments to pursue their wildest dreams and papering over their economic cost. Specifically, the natural gas boom encouraged the government of Evo Morales to dust off the 1970s policy toolkit, heavy on import substitution and nationalization of “strategic” industries. It didn’t work in the 1970s either.

Starting in 2007, Bolivia u-turned on two decades of market-oriented policy, during which it privatized some 100 state-owned companies. The Morales government nationalized the main companies in strategic sectors like oil, electricity and telecommunications. It ventured into other enterprises, like a state-run airline, Boliviana de Aviación.

Gas riches, the thinking went, would not only fund redistribution via direct social spending, energy subsidies and the like. They would finance a robust industrial policy to push the Bolivian economy upstream and allow it to diversify from its narrow commodity base.

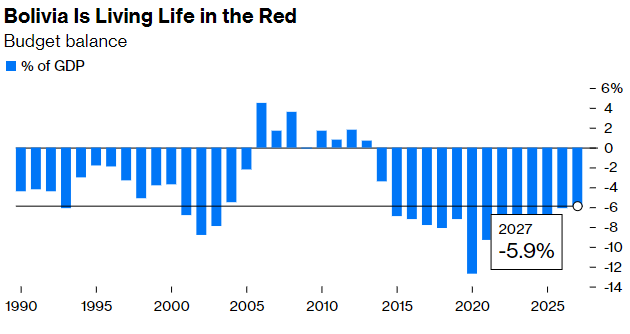

It worked, for a while. Gas revenues managed to sustain the kind of budget deficits required by this sort of economic strategy. But after gas revenues started waning in 2014, the mix of substantial budget deficits and a fixed exchange rate became increasingly hard to support. “Just like in the 1970s public companies are mostly running deficits,” Machicado said. “And they are consuming lots of Bolivia’s dollar reserves.”

Imports of diesel and gasoline have turned Bolivia into a net importer of hydrocarbons. The country now runs a substantial current account deficit. And dwindling dollar reserves suggest that if Bolivia can’t get its hands on some new source of external finance, it will be hit by a devaluation, just as it was in 1978.

The country might not be quite as vulnerable as it was back then. Dollar reserves may be shrinking, but the country still has some. Moreover, Bolivia’s foreign debt is much more manageable. It faces few maturing loans. “We can hold on for 1-2 years,” Machicado suggested. Perhaps the lithium will have kicked in by then.

_________________________________________________________

Eduardo Porter is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Latin America, US economic policy and immigration. He is the author of “American Poison: How Racial Hostility Destroyed Our Promise” and “The Price of Everything: Finding Method in the Madness of What Things Cost.” Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on March 29, 2023. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

energiesnet.com 03 30 2022