By Javier Blass

AT AN industry gathering organised by the Oxford Institute for Energy Studies last week, the crowd of executives, policymakers and consultants was asked whether the European Union (EU) would again make Russia its key gas supplier.

The straw poll showed a split of 40 per cent to 40 per cent, with the rest undecided.

I am with the “yes” crowd – even if Vladimir Putin stays in the Kremlin. As much as European leaders vow they will not return to business-as-usual after the war in Ukraine, the inescapable realities of geography and markets can trump even the most determined policymakers.

Whether that comes to pass or not matters not just for European energy markets – and its industrial behemoths – but also for the future of gas investments in countries from Qatar to Mozambique and the US. Billions of dollars in gas export facilities are at stake.

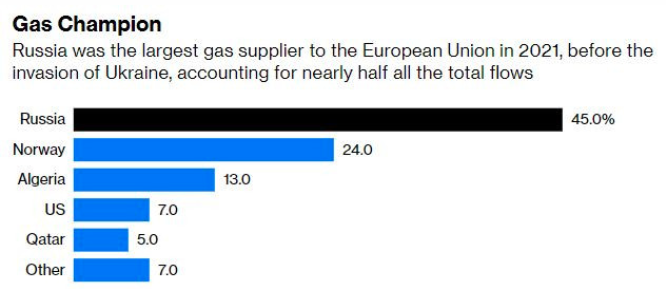

First, a bit of history. Before Putin ordered the invasion of Ukraine, Moscow supplied Europe with roughly 40 per cent of the gas it consumed. The energy bridge, built over decades, had withstood the coldest episodes of the Cold War, the disintegration of the Soviet Union and the liberalisation of the European energy markets.

Everything changed in February. Putin turned gas into a weapon, cutting exports to one European country after another, hoping to fracture the bloc’s pro-Ukraine unity. The region still buys lots of Russian liquefied natural gas (LNG), but pipeline exports have plunged. The share of Russian gas in the European mix will drop in 2023 to less than 10 per cent. While the EU has banned oil imports from Russia, it has not done the same with Russian gas.

The International Energy Agency has modelled a scenario, however, that shows Russian gas flows into Europe falling to a trickle by 2025, and to zero by 2028, through a mix of more LNG imports and greater production from solar and wind farms. The agency said it assumed the rupture of Russian-European gas trade would be “permanent”.

In European capitals, officials are adamant they have learnt their lesson. “We will only be truly free when we can do without Russian gas altogether,” Austrian Energy Minister Leonore Gewessler said last month.

Closer to ground level, views are more diverse. Michael Kretschmer, leader of the German state of Saxony and a prominent Conservative politician, said last month that going forever without Russian gas would be “historically ignorant and geopolitically wrong”.

For many German politicians, prices matter. Berlin is currently paying 140 euros (S$199) per megawatt hour to import gas, about seven times more than the average from 2010 to 2020. To cushion its consumers and companies, Germany is spending billions on subsidies.

The history of oil gives examples of some unlikely comebacks. Take Iraq. The United Nations imposed a full embargo on Iraqi oil four days after the country invaded Kuwait in August 1990. Even after the US defeated Saddam Hussein a year later, Washington insisted on keeping the embargo to deprive him of the means to wage another war.

In 1996, the US lifted the embargo, replacing it with a system known as oil-for-food, allowing Saddam to use proceeds from crude sales for humanitarian needs. By 2001, the US was importing as much Iraqi crude as in early 1990 – all while Saddam remained in power in Baghdad.

Can the same happen with Russian gas and Putin? It is likely. Europe will probably never go back to the same long-term contracts of the past with Russia, and likely would need to import less gas as time goes by, thanks to renewable energy. But if it is going to keep its chemical, food and heavy industries competitive, it will need some cheap gas. And there is no cheaper gas for Europe than Russia’s.

In some ways, Kyiv may well insist that Europe buys Russian gas via the pipelines that criss-cross Ukraine from east to west. As part of any peace agreement, Russia would probably have to contribute to the cost of Ukraine’s reconstruction. That bill would run into the dozens of billions of dollars, if not more. How would the Kremlin – whoever leads it – pay for that?

The very same way Saddam – and successive Iraqi leaders until February 2022 – paid exactly US$52.4 billion in reparations to Kuwait: selling fossil fuels.

__________________________________________________________________

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He previously was commodities editor at the Financial Times and is the coauthor of “The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources.” @JavierBlas. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on December 12, 2022. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

energiesnet.com 12 19 2022