The world has a lot riding on the big wind turbine looming over the scrublands that carpet the southernmost tip of the Americas.

By Eduardo Porter

Punta Arenas, Chile — It does not look quite like the first spark of a new tech revolution. But the world has a lot riding on the big wind turbine looming over the scrubland that rolls along the southernmost tip of the Americas from the Strait of Magellan as far as the eye can see.

To hopeful Chilean government officials, the turbine and its attached tangle of pipes, vats and industrial sheds hold the promise of prosperity: a new economic engine, new export products, new industries.

To development experts, it looks like a chance to reshape the distribution of economic opportunity, offering the Global South a shot at development that so far has proven out of reach.

To the world, this is a critical tool in the battle against climate change.

This is Haru Oni, a complex assembled over the last year and a half some 25 miles north of town by a collection of Chilean and international firms — energy and mining companies, engineering firms, even a carmaker. Later this month it will become the first successful project to transform the relentless winds of Patagonia into a substance that is chemically identical to gasoline.

It is but a pilot — a 3.4-megawatt turbine to make some 35,000 gallons of synthetic gas per year. But the venture partners hope to scale the effort to where it will produce millions of tons of essentially carbon-free fuel.

The world will not only have taken a big step toward solving the problem of how to store and transport renewable energy. It will also have joined a new era: the era of hydrogen, which could map out a radically changed economic geography from that of the age of fossil fuels.

Russia and the petrostates in the Middle East will lose their stranglehold on the world’s energy supply when more countries exploit their renewable resources. Hydrogen could further reshape the global economy by giving countries long bypassed by the promise of industrialization a shot at development by leveraging their access to the sun and the wind. And because the capital-intensive hydrogen economy relies heavily on technological know-how to transform renewable energies into a storable, movable substance, it is harder to “capture” than a fossil fuel economy. That may allow some of the world’s poorest countries to exploit their energy resources without falling prey to the resource curse that has dragged so many of those endowed with hydrocarbon deposits into a miasma of corruption and stagnation.

In a world desperate to cut carbon emissions to zero by the middle of the century, hydrogen is something of a Hail Mary pass. But the high-tech fuel once dismissed as prohibitively expensive is now seen as essential to helping address a challenge that seems unsolvable without it. Last year, the International Renewable Energy Agency forecast that hydrogen would satisfy 12% of the world’s total energy demand by 2050, up from virtually nothing today, and account for about a third of the global demand for electricity. And that’s on the lower end of the forecast range. Bloomberg New Energy Finance put hydrogen’s contribution at 22%.

Not all of this has to come from wind or the sun. IRENA forecasts that about a third would be produced with other processes, including extraction from methane, which accounts for most of the hydrogen consumed today, sequestering the carbon dioxide it produces.

However it is made, hydrogen could solve some otherwise forbidding problems with the world’s carbon-reduction strategies.

Synthetic fuels could power transoceanic ships and aircraft, which can’t be plugged into the power grid. Hydrogen could power industries like steel, glass and cement — which suck up massive amounts of energy to produce heat. A single steel plant using hydrogen to reduce iron would use about 300,000 tons of hydrogen per year and emit no carbon dioxide.

More broadly, hydrogen could speed the transition to an energy infrastructure that relies largely on electricity, which is very difficult to store and move around, powered by the sun and wind — intermittent energy sources that do not shine and blow 24/7.

Patagonia is a long way from the rest of Chile. Moving electricity from its windswept plains to the center of the country, where most of Chile’s population and industry are concentrated, would require building transmission lines tracking a thousand miles of complicated topography along the Andes mountain range.

“The challenge was how to export this energy,” says Rodrigo Delmastro, general manager of HIF Energy, part of the consortium running the Haru Oni project. “We are so far away.” Haru Oni’s synthetic fuels solved the challenge. They can be moved in trucks and trains and ships, just like a fossil fuel.

Hydrogen is what Haru Oni makes first. The electric power generated by the turbine is used to split water, or H2O, into H2 plus O through a process called electrolysis. The hydrogen is mixed with oxygen and carbon — which will be captured directly from the air in the pilot but drawn from wood chips and other biomass in future stages — to make methanol, one of the simplest alcohols. The methanol molecules are then transformed into gasoline, a more complex carbohydrate, that can be burned while adding no net carbon into the air.

This gasoline, says Delmastro, offers several advantages. Critically, it works in regular automobile engines. It offers a path to zero carbon emissions that doesn’t require replacing the world’s vehicle stock with all-electric vehiclesThanks,. Porsche, another member of the consortium, has committed to buy the synthetic gas the complex will produce.

There are other ways to store and move the hydrogen. The most common is to use it to make ammonia, which today is used mostly to produce fertilizer. Ammonia could be deployed to store energy or used directly as a fuel. Hydrogen could also be liquefied, chilling it to minus 253C (-423F), for storage and transport. Or it might be moved through pipes as a gas.

Haru Oni is just a toe in the door. Its turbine is only the seventh in all of Magallanes province. But others are coming. By the middle of the decade, the partners in the project hope to deploy a 320-megawatt wind farm on 3,700 hectares connected to electrolyzers, which would produce about 100,000 tons of synthetic methanol a year. A subsequent phase involves three lines each producing 7.8 million tons annually.

France’s Total-Eren and Britain’s Teg are flocking to the region to produce ammonia. “There’s been a gold rush for land,” Delmastro noted, providing a welcome windfall to the sheep farms now occupying the vast grasslands.

Government officials hope that wind can transform the backwaters on the southern tip of Chile, drawing power-hungry industries like steelmaking to its newly energy-rich lands. But the ambition is greater. In the capital of Santiago, the talk is about a new economic dawn fueled by renewable energy.

Julio Maturana, Chile’s undersecretary of energy, projects that the nation could have 35 gigawatts of renewable power deployed to produce hydrogen by 2030, fueled by wind power in the south and the vast solar resource of the Atacama Desert in the north.

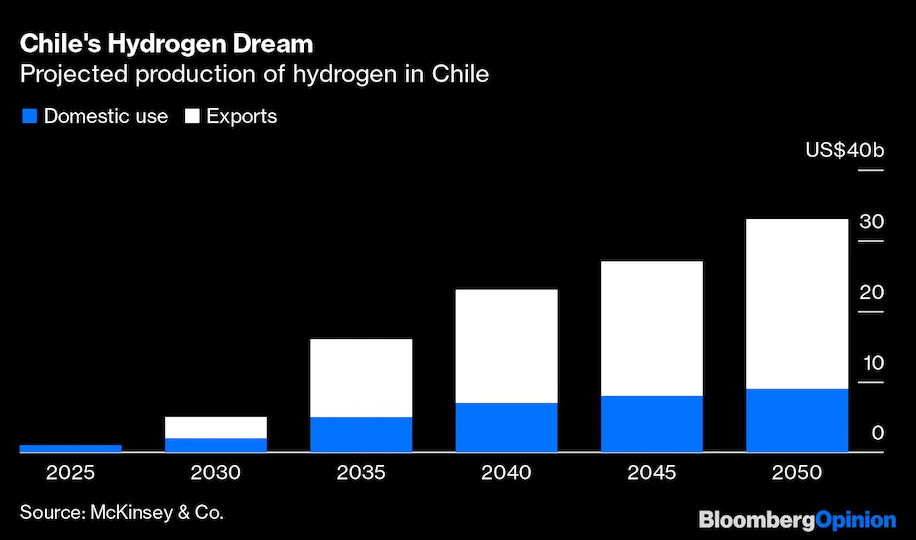

This won’t provide just a path to net zero by midcentury. The government expects exports of hydrogen and its derivatives to add up to $24 billion a year by then, about the same as the country reaps today from its top export product: copper. Moreover, it hopes the hydrogen revolution will draw investment north of $300 billion over the next three decades.

Chile is in a unique spot. According to a McKinsey study from 2020, the “unparalleled renewable resources in the Atacama and Patagonia make it the lowest cost place to produce Green Hydrogen in the world.” The consulting firm estimated that by 2050, Chile could produce a kilogram of hydrogen, which packs about the same energy as a gallon of gas, for as little as 80 cents to $1.10.

Hydrogen could also spread opportunity across the developing world. Large chunks of Africa and the Middle East get some of the most intense solar radiation in the world, and a lot of wind, too. Last year, Bloomberg New Energy Finance estimated that many countries in the Global South — including Mexico, India and China — could be producing hydrogen for less than $1 per kilogram.

IRENA forecasts that in 2050, hydrogen, ammonia and methanol will account for over a fifth of the world’s $1.6 trillion energy trade.

Several European countries are cutting deals with African countries to develop hydrogen for export to Europe from their wind, hydro and solar resources. Germany has set up so-called hydrogen offices in Angola and Nigeria to facilitate dialogue with these potential hydrogen exporters.

Africa’s first solar-powered hydrogen plant, built by a French company in Namibia with a capacity of 85 megawatts, is slated to start production in 2024. And the country’s goal is to have 3 gigawatts of solar-powered capacity dedicated to hydrogen to produce ammonia by the end of the decade. It also hopes to attract a green steel mill and a fertilizer production line.

Will hydrogen supercharge global development? A newfangled hydrogen era still requires several things to fall into place. Cheap as it has become, renewable energy from the sun and wind must keep getting cheaper. So must electrolyzers, as electrolysis accounts for about 30% of hydrogen’s cost.

Julio Friedmann, chief scientist at carbon management adviser Carbon Direct, notes that the hydrogen revolution is short of not only electrolyzers, but also transformers, electricians, engineers and specialty welders to build and install them. “Electrolyzers now cost $800 per kilowatt,” Friedmann said. “Maybe we can get it down to $500 per kilowatt, but to get hydrogen to $1 per kilo, we must reach $100 per kilowatt.”

Turning hydrogen into synthetic fuels is not cost-free. Neither is liquefying it at ultra-low temperatures, which requires enormous amounts of energy. Even if we could afford to produce liquified hydrogen, we would need ships to move it. (Today, the world has one hydrogen tanker, made in Japan.)

Storing gas hydrogen is still a largely unresolved challenge. And the world doesn’t have a ready network of pipelines sufficient to move it around at scale.

Critically, hydrogen-making requires a ton of capital investment upfront. Finding that money will not be easy for poor countries. “It is a capital cost game,” Friedmann said.

There are environmental challenges. Delmastro notes that massifying hydrogen production in Magallanes province must overcome stiff opposition from groups worried about the impact of wind turbines on the ruddy-headed goose, which flocks to the area.

And the hydrogen revolution faces the chicken-and-egg problem: Investors won’t risk sinking money into infrastructure until they are sure of demand for the newfangled fuel, but unless the investments are made to achieve economies of scale, hydrogen will remain too costly to justify the switch to the new energy source. “We’re not going to jump into the pool until we have closed with the takers,” says Fernando Meza, who heads business development in Chile for Enel Green Power, one of Haru Oni’s partners.

Still, a Global South bracing for the wallop from a changing climate can hope that the battle to mitigate carbon emissions might also unlock an unprecedented opportunity to move up the income scale.

Unlike oil and gas, renewable energy is not quite an extractive resource. Harnessing it and turning it into hydrogen or some synthetic fuel requires developing technological know-how. From Chile to Namibia, the hope is that the new geography of energy brought into being by the transformation of wind and sun into clean hydrogen will open wider horizons than did the 20th-century paradigm of pumping hydrocarbons from the ground.

_____________________________________________________________

Eduardo Porter is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Latin America, US economic policy and immigration. He is the author of “American Poison: How Racial Hostility Destroyed Our Promise” and “The Price of Everything: Finding Method in the Madness of What Things Cost.” Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on December 13, 2022. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

energiesnet.com 12 14 2022