Shery Ahn, Bloomberg News

NEW YORK

EnergiesNet.com 02 17 2023

Visitors to Chile’s Punta Arenas, one of the southernmost cities in the world, should beware: Winds of as high as 120 kilometers per hour (75 miles per hour) can easily topple the unwitting pedestrian. Ropes have been strung up between some of the buildings in the city’s downtown to give people something to grasp during a gust.

Capitalizing on Chile’s powerful winds is an important agenda item for President Gabriel Boric, who assumed office almost a year ago promising to green an economy dependent on fossil fuels and copper mining. Renewables already account for more than 50% of the country’s electricity generation capacity, and that proportion is set to continue rising as the government works toward the goal of closing or repurposing all coal-fired plants by 2040 at the latest

Chile is seeking to lure private investors to harness the country’s winds for commercial purposes, partly to cushion the blow from the energy transition on certain communities. “Because many of our industries, like oil in the south and coal in the north, are slowly dying in this green world, we need to give those communities an alternative to keep working and provide economic stability,” says Minister of Energy Diego Pardow.

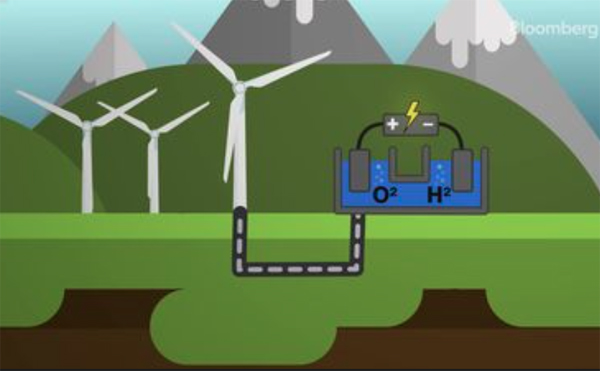

Haru Oni, a $74 million pilot project located about 40km north of Punta Arenas, is the fruit of these efforts. On a site surrounded by nothing but brush, a giant wind turbine towers over a collection of buildings, one of which houses an electrolyzer, a machine that splits water molecules into oxygen and hydrogen. The former is released into the atmosphere, while the hydrogen is captured and combined with carbon dioxide to make methanol, a gasoline substitute that burns more cleanly. Germany’s Siemens Energy and Porsche, along with Enel, an Italian energy company, are partners in the venture, which was announced in 2020 and became operational at the end of last year.

“Anything we do today with petroleum, synthetic fuels can do tomorrow. Whether that’s plastic, chemicals or transport, we’ll be able to replace fossil fuels with something that’s synthetic and green and is made from renewable energy,” says Clara Bowman, chief operations officer at HIF Global LLC, the project’s lead developer.

Almost all hydrogen produced globally is what’s known in the industry as “gray,” meaning it’s extracted from fossil fuels—primarily natural gas, but also coal. Diesel refineries and makers of fertilizers are among the main customers. In contrast, much of the excitement around green hydrogen centers on its potential as a substitute for dirty fuels used in transportation, including rail and shipping.

Chile has set itself the goal of becoming one of the top three exporters of green hydrogen by 2040. Analysts at BloombergNEF reckon the country has the potential to be one of the lowest-cost producers in the world, achieving a levelized cost as low as $1.09 per kilogram by the close of the current decade. (Levelized cost is a measure that accounts for all the capital and operating costs of producing a certain type of energy.) “Chile’s government was the first to set a hydrogen strategy in Latin America. This is a strong signal to developers and future clients,” says BNEF analyst Natalia Castilhos Rypl. “Brazil may become the largest producer in the region, but Chile is leading the way right now.”

Chile already has 41 green hydrogen projects underway. Haru Oni is among the most advanced: The plant delivered its first batch of synthetic gasoline in December, with production slated to climb to 130,000 liters by yearend. Its only customer at the moment is Porsche AG, which uses the fuel in demo vehicles. The plan is to eventually diversify the customer base to include shippers and airlines.

The fuel produced at Haru Oni will be transported about 35km by truck to a port for export, which avoids the need to build a costly pipeline infrastructure. “Because we’re using liquid fuel, whether methanol or gasoline, we can use regular ships to move fuel around so it’s actually not that expensive,” Bowman says. Chile’s geographic location is also an advantage, she says, with access to both the eastern and western US, as well as Asia and Europe.

HIF Global says the plant has benefited the local community, with Punta Arenas residents making up more than 80% of its 250-person workforce. But not everyone has been welcoming.

Local environmental groups are voicing concerns about the large wind farms needed to produce green hydrogen at commercial scale. “All this region could be covered with windmills, and we don’t know the migratory routes of over 60 species of birds that inhabit Patagonia,” says Ricardo Matu, director at Leñadura Bird Rehabilitation Center. “We’re trying to figure all this out on record time, but you cannot do this in a rush.” It’s not only birds such as the endangered Magellanic plover that could be affected. The populations of dolphins and whales could also suffer if the region experiences an increase in maritime traffic.

HIF Global and Enel SpA have hit pause on plans to set up a larger, commercial green hydrogen plant in the area that would produce 66 million liters (about 17 million gallons) of fuel starting in 2026. “We realized there was still more dialogue to be had with the authorities regarding the standards they’re looking for in these projects,” Bowman says. “This is understandable given it’s something that hasn’t been done before.”

Pardow says he’s confident that the project will be able to move forward this year. “It’s a learning process. We’re reinforcing the local team with professionals who are able to help assess the environmental impact of projects,” he says. Chile’s energy minister is well aware that projects such as these could become a test of how well the country’s most leftist government in a half-century works with private capital. “We will keep the promises made to companies that have invested in Chile,” he says, adding that more grants and loans are forthcoming, as authorities also work on easing land-use rules to attract more businesses to Chile’s budding green hydrogen industry. —With Eduardo Thomson

bloomberg.com 02 16 2023