By John Kemp

Prior to the advent of the modern petroleum industry and the rapid growth of kerosene lamps for illumination, the most prized source of artificial light came from bright and sweet-smelling spermaceti candles, made from the head matter of sperm whales. Spermaceti candles were expensive, which put them out of reach of lower-income households, but they provided more illumination, with less unpleasant odour and less risk of starting an accidental blaze than the alternatives.

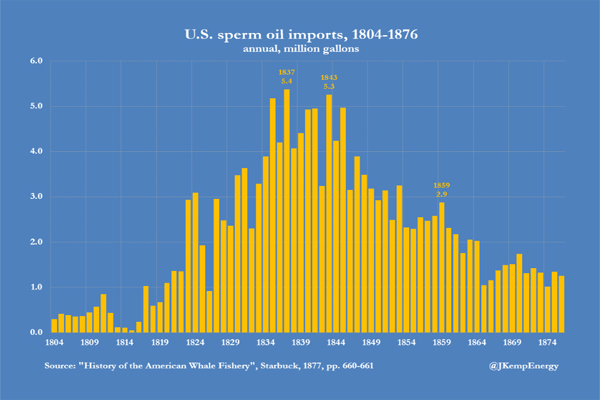

Before Edwin Drake drilled his first successful well in Pennsylvania in 1859, however, spermaceti was already becoming increasingly scarce and prices were climbing sharply as a result of overfishing, escalating costs and crew shortages. Sperm oil imports into the United States (the amount declared to customs on landing) had halved to 2.6 million gallons in 1858 down from 5.3 million gallons in 1843. The landed price of sperm oil had doubled to $1.21 per gallon from just 63 cents.

Spermaceti availability was declining primarily because of overfishing, which forced whaling ships further offshore and on longer voyages, and even then they increasingly came back with less than a full load. The industry’s cost base was also rising as ships were fitted out to higher and more modern standards.

Once the California gold rush was underway, crewing became a major problem. Sailors would contract for a lengthy voyage from the U.S. east coast to go whaling in the Pacific, collect their sign on bonus, enjoy free passage to the Pacific, then jump ship when they reached California to try their luck in the gold fields, delaying voyages and requiring costly extra hires.

Spermaceti as a source of illumination was already in trouble before Drake’s well. It could never have satisfied the growing demand for lighting. The sudden competition from a plentiful source of cheap lighting in the form of petroleum-derived kerosene accelerated the industry’s decline. By the late 1870s the whale fishery had become a shadow of its former self.

The U.S. civil war squeezed the industry further in the early 1860s. Whaling acted as the “nursery for seamen” supplying the most experienced sailors in the United States (just as the east coast coal trade in England acted as the nursery for the Royal Navy in the 17th and 18th centuries). Once war broke out, sailors were diverted to naval service.

For all these reasons, the number of U.S. whaling vessels active in the North Pacific dwindled to just 32 in 1862 from 278 ten years earlier in 1852. The number of active vessels never really recovered. After the hostilities ended, it increased to a post-war peak of 95 in 1866 but by 1876 had fallen to just 8.

The industry’s rise and fall was memorialised in the “History of the American Whale Fishery” by Alexander Starbuck, written at the request of the United States Commissioner of Fish and Fisheries, and published in 1877. Starbuck’s mammoth report served as an epitaph for the whale oil industry as it became increasingly marginal:

“The increase in population would have caused an increase in consumption beyond the power of the fishery to supply, for even at the necessarily high prices people would have had light. But other things occurred. The expense of procuring [whale] oil was yearly increasing when the oil-wells of Pennsylvania were opened, and a source of illumination opened at once plentiful, cheap, and good. Its dangerous qualities at first greatly checked its general use, but, these removed, it entered into active, relentless competition with whale-oil, and it proved the more powerful of the antagonistic forces.”

The replacement of whale oil by petroleum is a fascinating case study of an energy transition, with multiple factors driving a relatively rapid shift from one fuel source to another.

The chartbook presents a few selected statistics on the rise and fall of the U.S. whale oil industry in the 19th century, all taken from Starbuck’s book: https://jkempenergy.files.wordpress.com/2024/03/us-sperm-oil-production.pdf

____________________________________________

John Kemp is a senior market analyst specializing in oil and energy systems. Before joining Reuters in 2008, he was a trading analyst at Sempra Commodities, now part of JPMorgan, and an economic analyst at Oxford Analytica. His interests include all aspects of energy technology, history, diplomacy, derivative markets, risk management, policy and transitions.

Reuters.com 03 10 2024