By Javier Blas

Europe is sweltering under a heat wave that has pushed temperatures above 40 degrees Celsius (104 degrees Fahrenheit) in several countries. As households and businesses turn on their air conditioners, electricity demand has jumped and wholesale power prices have surged. But far more concerning — and far less discussed — is the drought spreading from Germany to Portugal that has the potential to worsen the current energy crisis for a lot longer than the current hot spell.

The drought is a gift from nature for Vladimir Putin, making Europe even more reliant on Russian natural gas at a time when the Kremlin is reducing supply sharply. Last winter, the weather favored Europe, as unseasonably high temperatures during the Christmas holidays cut demand for energy; now, the lack of rain is working against the continent.

That winter bonus came at a price, with the Alps, the Pyrenees and other mountain ranges getting less snow than usual. Water levels in the Rhine dropped precipitously by late winter and early spring, but the snow melt in May and June masked the crisis for a while. Since then, large swathes of Europe have received very little rain. Now the problems are re-emerging, and are widespread across the continent. The list of European drought-stricken rivers is long, including the Rhine, the Ebro, the Rhone and the Po, among others.

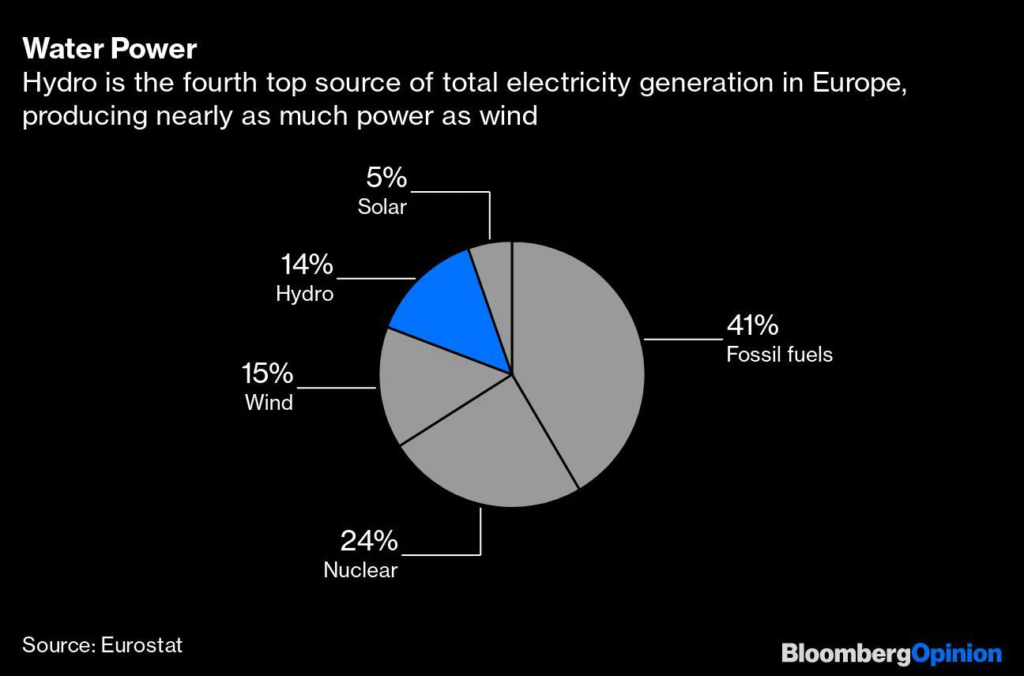

The drought matters for electricity beyond hydropower generation. Coal-fired power stations in Germany rely on waterways such as the Rhine to ship in their fuel via barges. And French nuclear plants rely on rivers for cooling. If hydropower, coal and nuclear production is disrupted, all Europe has left is wind and solar, both subject also to the vagaries of the weather — and natural gas.

The water level at Kaub, a picturesque town south of Cologne on the Rhine, is paradigmatic of the crisis. On Tuesday, the gauge stood at 104 centimeters, the lowest at this time of the year in at least 15 years. On average, the river typically flows at a level of more than two meters through the town in July. Even in 2018, when the Rhine suffered its worst drought in a century, the water level at Kaub was slightly higher it is now.

Upriver, at the Maximiliansau gauge, the water has dropped to its lowest seasonal level since at least 2005, endangering shipping to French and Swiss industrial and commercial hubs including Strasbourg, Mulhouse, and Basel. The big drop upstream signals that the middle and lower Rhine will soon be even drier.

The problems in the Rhine are well documented as it’s dotted by dozens of metering stations that allow investors to gauge the water level by the minute. But multiple waterways in Europe are suffering equally, even if they generate fewer headlines. For example, the Po, the longest river in Italy, is enduring its worst drought in 70 years.

The first casualty is hydropower generation, forcing the likes of Spain and Italy to burn more gas at a time when every cubic meter is expensive. Seasonally, Spanish hydro generation is running at the second-lowest level in 20 years. In France, hydro generation is the weakest in a decade. In a typical year, hydropower is the fourth-biggest source of electricity across the European Union, after gas, nuclear and wind, generating nearly 14% of all the electricity.

Worse could come. Electricite de France SA, which runs the biggest fleet of nuclear power stations in Europe, has warned it’s likely to trim output at some atomic plants this summer as the drought reduces the amount of river water available for cooling. The French company, which has closed dozens of reactors to check their welding, was forced last month to curb output at its Saint-Alban nuclear plant, nearly Lyon after the Rhone river level dropped. Another five EDF nuclear plants are at risk, the company said last week.

For now, coal-fired power stations appear well stocked, having used the period of high water during the spring snow melt to replenish their inventories. But they’re not immune; the Karlsruhe generator in Germany is already reporting resupply issues, suggesting the problems will re-emerge sooner rather than later, potentially hitting Germany at the worst possible time. The Rhine is the cheapest, and easiest, way to transport coal from Rotterdam into southern Germany.

So when gauging what happens next in the energy conflict between Europe and Russia, keep an eye on the sky. And pray for rain

___________________________________________________________________

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He previously was commodities editor at the Financial Times and is the coauthor of “The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources.” @JavierBlas. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on July 13, 2022. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

energiesnet.com 07 13 2022