Corruption seems so fundamental to the business of mineral extraction that it’s almost winked at. When Rio Tinto Group announced in 2016 that it was firing two senior executives over $10.5 million of payments made in connection to a mining project in Guinea, investors looked instead to the booming iron ore price and shares rose 6.8%.

This week it’s been Glencore Plc’s turn to collect the wages of sin. The stock rose as much as 5.3% Tuesday, putting it just 0.03% below its all-time high, after it admitted to bribery and market manipulation and agreed to pay a $1.1 billion settlement with authorities in the US, UK and Brazil over a decade of corrupt practices that stretched from Houston and Los Angeles to Nigeria, Equatorial Guinea and the Democratic Republic of Congo.

The settlement certainly removes a cloud over the stock that’s been hanging around for a while. Though Glencore’s mix of mining and trading operations is unique among listed companies, it arguably trades at a discount to its closest peers — a factor that may well be connected to the disreputable whiff around the company since it was formed from the ashes of fugitive commodity trader Marc Rich’s eponymous business.

A more telling factor, though, is that the settlement is evidence Glencore is good at doing the job its shareholders want it to do: extracting the maximum value from global flows of commodities and funneling it toward investors.

As we’re seeing around the war in Ukraine, where European oil companies have been mixing Russian crude with other varieties to disguise the unpalatable origin of their cargoes, the trading business has always thrived on ensuring consumers don’t think too hard about the sources of their raw materials.

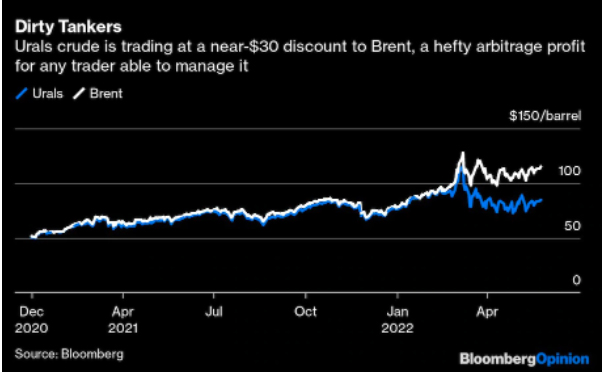

Urals crude is selling at a $30 discount to the Brent equivalent at present. For traders prepared to get their hands dirty with the legal but ethically dubious business of dealing in that product, it represents notional arbitrage profits of close to $150 million a day. One of Rich’s greatest coups was selling Iranian oil to Israel after the 1979 Islamic revolution, brokering a deal that neither nation was prepared to publicly countenance.

The business of a commodity trading house depends on getting access to vast amounts of product. Glencore doesn’t produce crude in any significant quantities, but the 706 million barrels it bought from third parties and sold onward last year was equivalent to about 2% of global output. Add in the volumes of petroleum products such as gasoline and diesel, and you’re closer to 4% of the world market.

Finding barrels that aren’t already locked up by the major national oil companies and the listed oil majors often involves going to places they’re less willing to venture. Of the $2.1 million of payments Glencore made in 2020 that were disclosed under the EU’s anti-corruption laws, more than a third went to countries that rank in the bottom half of Transparency International’s index of perceived graft.

In theory, it’s possible to make an ethical payment to even the most kleptocratic of governments. Still, the evidence presented by the US Department of Justice — outlining more than $100 million that Glencore spent to funnel bribes to officials in Nigeria, Cameroon, the Ivory Coast, Equatorial Guinea, Brazil, Venezuela and the Democratic Republic of Congo — suggests these relationships fall into criminal territory far too often.

Glencore’s customers should be just as concerned about the other side of its criminal settlement. Roughly 70% of the fines levied by US authorities related not to corruption in sub-Saharan Africa, but market manipulation in US commodities hubs, where traders fattened their margins with a scheme straight out of “Trading Places”: putting in bogus “sell” orders for fuel oil to depress the value collated by the price-setting agency S&P Global Platts, then buying the contracts based on the artificially deflated benchmark price (and vice versa).

Such activity has at times been an almost routine practice in many markets, with billions of fines paid over the past decade for manipulation of foreign exchange and Libor benchmarks. Commodities still present a target-rich environment, with plenty of obscure micro-markets where price-setting is more art than science. Some of Glencore’s major products, such as coal, ferrochrome and cobalt, are sold into just such illiquid markets. Even a relatively significant LME-traded metal like nickel isn’t immune.

Glencore wants to draw a line under such behavior. It’s no longer “the company it was when the unacceptable practices behind this misconduct occurred,” Chairman Kalidas Madhavpeddi said, adding that board and management are committed to creating “value for all stakeholders.” That’s an admirable ambition — but its equity investors, who care most about the value it creates for shareholders alone and include many of the senior executives who were in charge when the wrongdoing took place, will no doubt hope that won’t mean too much moral rigidity.

In a business that thrives on the thin margins that commodity traders live on, the $1.1 billion fine it will pay out looks like small change for a company that posted revenue of some $2.34 trillion and operating cashflow worth $76.58 billion in the relevant period. For all its diligent ESG reporting, no one invests in Glencore because they want to add some ethical sheen to their portfolio.

______________________________________________________________

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on May 25, 2022. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

energiesnet 05 26 2022