By Ziad Daoud

To understand the scale of Gulf nations’ wealth, just consider this: If the United Arab Emirates sold its stash of foreign holdings, it could make every one of its roughly 1 million citizens a millionaire. Qataris would enjoy the same windfall. Saudi Arabia, with its larger population, wouldn’t hit a million dollars per citizen, but the share allotted to each one would still be close to the average annual income in the US—a hefty sum.

Of course, that leaves out the large share of those countries’ populations who aren’t citizens—not to mention that these states have no intention of simply dividing up and distributing their hoards. That’s not what the money is for: It’s for securing the future. The Gulf is awash in oil revenue. The value of daily crude exports in 2022 and 2023 topped $1 billion, leaving enough after paying for imports to fuel massive savings. But the world is transitioning away from oil and gas, and these nations need to diversify.

So they’re building up portfolios that have made them major forces on the global investment scene, with holdings that include American tech companies, English football clubs, Egyptian real estate, African mines and Turkish bank deposits. Four of the world’s top 10 sovereign wealth funds are from the region, those belonging to Kuwait, Qatar, Saudi Arabia and the UAE. The Gulf is close to becoming the only region with three separate wealth funds exceeding $1 trillion each. Asset managers, private equity partners and venture capitalists from New York, Silicon Valley and London pack the business-class cabins of Emirates and Etihad Airways A380s to pitch their services and idea

Money isn’t just an economic tool; it’s also a political weapon. The Gulf nations are using their petrodollar wealth to wield influence on the world stage—placing investments to further strategic goals. Turning hydrocarbons into geopolitical muscle isn’t new: The oil embargo in 1973, when Arab states stopped selling oil to countries supporting Israel, leading to a fourfold increase in the price of crude, is only the most famous example.

What’s different now is that the Gulf’s leaders are taking a riskier investment approach to generate higher financial returns. They’re also looking to cultivate soft power, ensuring the world sees the Gulf in a favorable light.

The Gulf nations’ decisions ripple around the globe. Their investments can affect the cost of borrowing for the US, their key security partner. Their cash can provide an alternative to China’s financing in an increasingly polarized world. And their aid and other support can help stabilize troubled economies and make or break International Monetary Fund bailouts.

But the process also carries risks for the Gulf. Its countries’ objectives can at times be contradictory—engagements in Sudan or Yemen may make sense strategically, but there’s a price to be paid in lives lost and international opprobrium. Gulf powers are often at odds with each other on foreign policy. And moving away from oil requires political change as well as savvy investment decisions.

Like all investors, the Gulf states are pushing to maximize returns from their savings. The stakes are higher than simply putting ever-bigger numbers on the account ledger. Oil has created a social contract: economic prosperity for citizens in exchange for their loyalty to an absolute monarch. The hydrocarbon windfall has been funding the pact, but oil prices are volatile, and every electric vehicle that rolls off the assembly lines of Tesla Inc. and China’s BYD Co. is a reminder that nothing lasts forever.

Non-energy investments can generate earnings that offset some future oil losses. Saudi Arabia’s Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman laid out this strategy in 2016. His aim was to “make investments the source of Saudi government revenue, not oil.” Traditionally, Gulf nations parked a large share of their wealth in safe assets, such as cash, bank deposits and US debt. Now they’re aiming to generate a higher yield. Qatar’s wealth fund, for example, favors stocks, real estate and infrastructure investments. Similarly, the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority allocates most of its nearly $1 trillion in assets to stocks, real estate, private equity and infrastructure.

Metals are another target investment. As the world transitions to clean energy, metals such as copper—used in power transmission and batteries—would be in high demand. The Gulf nations have been investing in mines and metal-trading companies. The UAE has bought a copper mine in Zambia. Saudi Arabia wants to increase metal mining’s role in its economy. Oman has plans for the world’s largest green steel plant.

Food security is another concern. The Gulf lacks arable land and water for irrigation, and it relies heavily on food imports. The pandemic and the war in Ukraine, both of which rocked global supply chains, have exposed how risky this is. The UAE, Saudi Arabia and Qatar are now actively acquiring farmland across Africa, Europe, Asia and Australia. Some of their sovereign wealth funds have dedicated units specifically focused on securing food supplies.

In short, the Gulf nations are playing a multipronged game—diversifying their investments while also securing their access to resources. But the payments they receive from oil and gas are too large to be replaced with dividends from sovereign wealth funds, even with their massive size, no matter the investment strategy. And as many pension fund and university endowment managers can tell you, there’s no free lunch in investing. Bets on SoftBank Group Corp.’s Vision Fund and the collapsed Credit Suisse have already provided the Middle East’s money men with an expensive lesson that higher risk doesn’t always bring more reward.

Japan famously overpaid for US assets in the 1980s and it also unintentionally stoked anti-Japan sentiment in the process. That backlash is worth keeping in mind when considering the other goal of the Gulf powers—boosting their image and influence abroad.

Soft power relies on persuasion, not coercion. It leverages culture and values, not guns or threats. Saudi Arabia has long been a soft-power heavyweight in parts of the world. Its role as custodian of Islam’s two holiest sites in Mecca and Medina gives it influence in the Muslim world. But times are changing. It’s attempting a rebrand, aiming to swap social conservatism for a more open image. It’s spending generously on tourism, entertainment and sports.

Qatar proves you don’t need a large population to be a soft-power player. Its Al Jazeera TV reaches far and wide, with huge influence in the Arab world. It’s flexing muscles in sports, too, owning a Parisian football club and having hosted the 2022 FIFA World Cup. In the UAE, Dubai aspires to be a dream destination, with its mix of economic prosperity and social—if not political—openness.

The power of money isn’t always so soft: Gulf states do plenty of hard economic statecraft, too. In the 1980s, they bankrolled Iraq’s war with Iran. In the 1990s they doled out money and offered debt relief to secure support from Egypt, Morocco and Pakistan against Iraq’s invasion of Kuwait.

This year the UAE is investing $35 billion in real estate projects in Egypt. The size of the deal—equivalent to 7% of the UAE’s gross domestic product—goes beyond simple commercial logic, hinting at a political motive. The most obvious one is maintaining stability in a region riddled with unrest, with civil wars in neighboring Libya and Sudan and a conflict raging next door in Gaza. The UAE investments helped Egypt secure an IMF deal and prevent an economic collapse.

Turkey, once an adversary of the UAE and Saudi Arabia, has more recently become a friend. The two Gulf countries stepped in with investments and deposits that helped stabilize the Turkish lira before President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan’s crucial elections in 2023—transfers that helped Erdoğan emerge victorious.

The UAE is actively investing in ports across the Horn of Africa. In her book The Economic Statecraft of the Gulf Arab States, Columbia University political economist Karen Young argues that these investments aim to counter Islamist politics and Iranian influence in the region. The latter is felt both in the Horn of Africa and across the Red Sea via the Houthi rebels in Yemen.

Petrodollars are also playing a role in war-torn regions like Libya, Sudan and Yemen, and they may one day in Gaza. The financial support they provide can significantly influence political outcomes in these territories. For African nations caught in the growing US-China rivalry, Gulf investments offer a welcome alternative. Many countries are wary of the historical baggage associated with Western aid and the potential debt burdens caused by Chinese loans.

Gulf money matters even for the world’s largest economy. Bloomberg Economics estimates that the inflow of Gulf savings into the debt market may have reduced US borrowing costs by 0.25 percentage point. Over the period from 2005 to 2023, that saved US taxpayers some $700 billion.

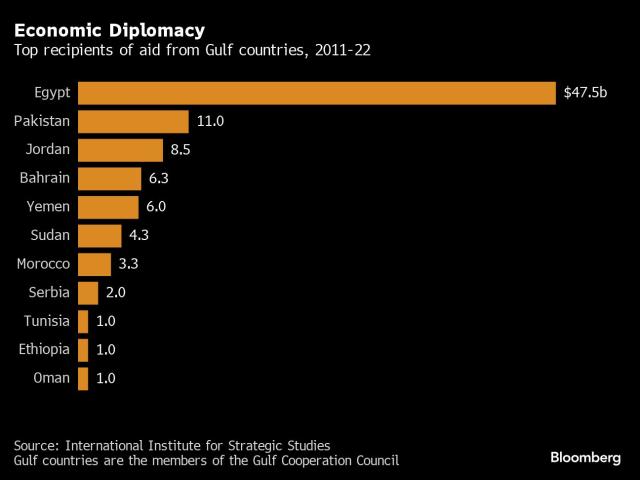

Petrodollar diplomacy isn’t without risks. For one thing, it’s expensive. From 2013 through 2022 the UAE, Saudi Arabia and Kuwait provided a combined $34 billion to Egypt in the form of cash grants, oil shipments and central bank deposits, according to data compiled by Hasan Alhasan and Camille Lons from the International Institute for Strategic Studies. In just a two-month period in 2024, the UAE is due to send more than that amount. Qatar spent about $300 billion to upgrade its infrastructure ahead of hosting the World Cup. Dubai went through a real estate crisis in 2009 amid the construction frenzy that delivered the world’s tallest tower.

The World Cup also brought international attention to conditions faced by many foreign workers building up Doha. In the US, Saudi Arabia’s funding of a professional golf tour triggered a Senate inquiry into the kingdom’s use of its wealth to extend its influence. And Democrats in the House of Representatives in March pushed for hearings on the business dealings and potential conflicts of interest of Jared Kushner, the son-in-law of former President Donald Trump. Kushner, who served as a White House adviser, now runs a fund that received a $2 billion investment from Saudi Arabia’s wealth fund after Trump left office. Kushner has said he won’t return to government if Trump wins his bid to regain the presidency.

Tunisia recently blocked a Qatari fund from opening a branch there. The decision meant sacrificing a quick $150 million injection into the economy and potentially more funding. Opponents saw the Qatari office as a threat to national sovereignty and a hindrance to self-reliance. They also questioned Doha’s alleged links to Islamist politicians. The episode shows that soft power may be hard to buy—and that reputations once established may be difficult to alter, no matter how much money a state throws at improving its image.

For now, research from Young at Columbia shows that the Gulf’s economic diplomacy hasn’t been sensitive to movement in oil prices. But a sustained drop in the energy market could suddenly deprive many countries addicted to petrodollar support of essential funds. Put simply, the Gulf’s investment and political choices will not only shape their own post-oil future but also the political landscape in developing countries and the global financial order.

________________________________________

Ziad Daoud, based in Dubai, is the chief emerging-markets economist for Bloomberg Economics. EnergiesNet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg, on April 24, 2024. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet or Petroleumworld, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

EnergiesNet.com 04 24 2024