Now that its much-trumpeted potential in the financial universe has been debunked, blockchain may find a place as a source of eccentric pursuit much like the made-up language.

By David Flickling

The rise and fall of cryptocurrencies over the past decade has been accompanied by an extraordinary degree of waste.

Trillions in notional market value was created, traded, and then evaporated. As much as 170 million metric tons of carbon dioxide is pumped into the atmosphere every year by crypto miners, equivalent to the carbon footprint of the Netherlands. Hundreds of thousands of computer mining rigs are sitting in unopened boxes, according to Coindesk, waiting for prices to rise enough to make connecting them profitable. In previous bear markets, truckloads of burned-out mining rigs have reportedly been sold for scrap.

Next to all those, though, there’s an extraordinary waste of human creativity. As Matt Levine chronicled in a recent Bloomberg BusinessWeek story, the institutions created by crypto enthusiasts were little less than a mirror financial system, complete with protocols for lending money, creating derivatives, writing contracts, and settling trades. The fact that this architecture was structurally compromised, and has collapsed under its own weight, doesn’t take away from the mass of ingenuity that went into creating it.

At an end-of-term party at my children’s school earlier this month, I found myself chatting to a friend about the collapse of FTX, the crypto exchange run by Sam Bankman-Fried. To my surprise, my friend — a thoughtful, gentle doctor and father of three — had a more than academic interest in the subject. Last year, he spent A$2,000 ($1,367) on crypto and treated it like a hobby, avoiding further investments and making and selling NFT art as a sideline. (1)

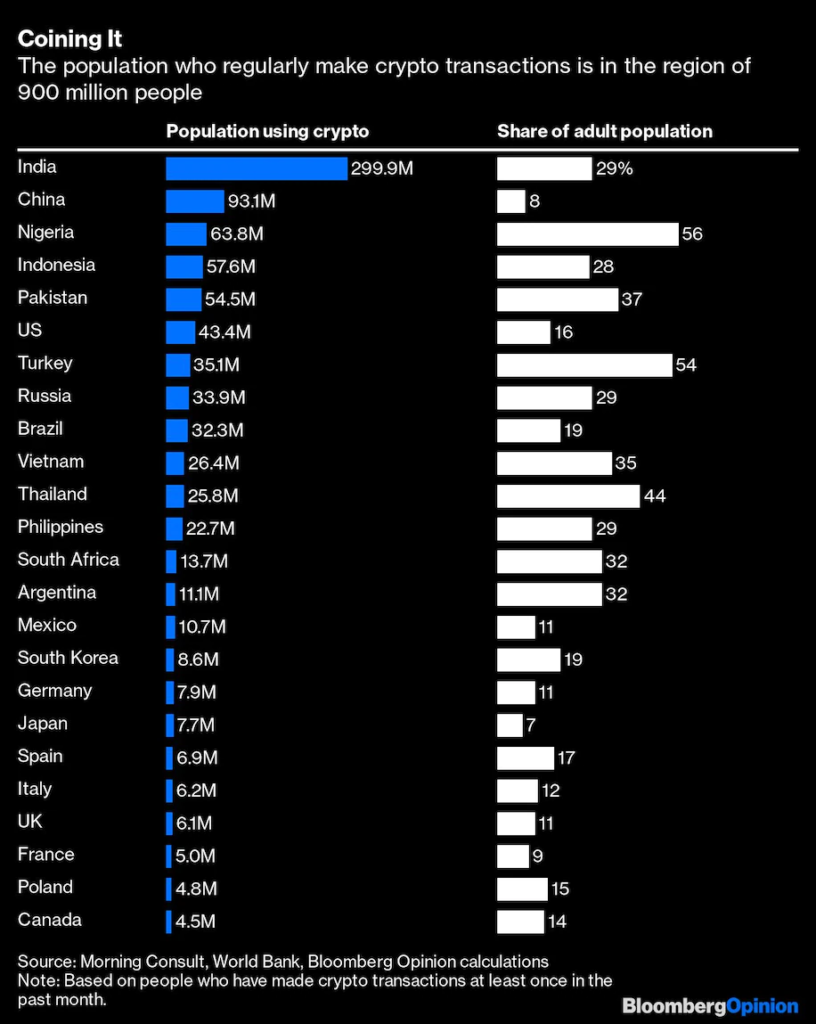

He’s scarcely alone. More than half of the adult population of Nigeria and Turkey buy or sell cryptocurrencies every month, according to a July survey by Morning Consult, a business data company. In all, in the region of 900 million people — around one in every seven adults on the planet — make regular transactions on the blockchain, based on the survey’s figures.

It’s impossible to know the motivation of all this activity. For all the attention garnered by testosterone- and adderall-fueled crypto traders and broke billionaires trying to escape the long arm of justice, the vast majority of players in crypto are likely to be doing it for more mundane reasons.

All that Nigerian and Turkish activity is likely driven by a very understandable desire by mom-and-pop savers to escape those countries’ foreign-exchange controls and double-digit inflation. Others will be doing it as a creative and intellectual outlet, like my friend. Others will buy crypto in the same way that they might have an occasional flutter on a lottery ticket or a horse race.

For the record, I’ve never believed any of the claims of crypto’s boosters — that it’s a viable alternative to fiat currency or a stable store of wealth, or even that it has any place in an investment portfolio. The fact that so many ordinary people have invested in crypto should worry governments, and make them much more ready not just to regulate the nascent industry but crack down on it to ensure people’s savings aren’t wasted on a Ponzi scheme. The fact that it’s pumping vast volumes of carbon into the atmosphere should encourage them to force activity onto the less harmful proof-of-stake protocol used by Ethereum, rather than Bitcoin’s emissions-intensive proof-of-work.

Nonetheless, you don’t have to believe the millenarian claims of blockchain’s online evangelists to think it deserves its place in the world. Plenty of human activities serve no very obvious fundamental need, and may even be mildly harmful, from art to gambling and fashion to drinking alcohol. The pleasure that people derive from such aimless activity should be recognized as a worthwhile end in itself.(2)

A better comparison might be another group of idealistic eccentrics which celebrates its annual holiday this Thursday. Speakers of the invented language Esperanto, developed by Polish ophthalmologist LL Zamenhof in 1887, have pursued their own hobby on a global scale for more than a century. The language has long been a pastime of brilliant, quixotic visionaries who’ve made a genuine impact in the non-Esperanto world — from the writers Leo Tolstoy and JRR Tolkien to figures such as Ho Chi Minh, Pope John Paul II, and George Soros.

Esperantists have their own flag and radio broadcasts, and have on several occasions tried to come up with a currency based on slightly creaky economics (one early variant was fixed to the price of bread in the Netherlands). To this day, they write Esperanto-language poetry and novels, hold annual conferences, and stay in each other’s houses when traveling. They even made a 1960s horror B-movie starring William Shatner, entirely scripted in poorly pronounced Esperanto. In short, they’ve created a remarkably fertile and sustainable worldwide community of oddball enthusiasts.

That suggests a more hopeful future for crypto than the current conflagration would suggest. Mandate deposit limits similar to those advocated for online gambling and shift activity away from proof-of-work, and it will be possible to balance the genuine interest of millions with the need to prevent harm to people and the planet.

Amid the ruins of 2022’s crypto bust, we should feel quite comfortable at that prospect. Almost every harmless amusement that humans engage in was once novel and frowned on by those who didn’t enjoy it. Someday soon, crypto and NFTs will join the ranks of such activities. Past their angry adolescence, they’ll no longer seek to change the world. They’re likely to find something better, though: The realization that often, happiness and undirected pleasure can be its own reward.

______________________________________________________________

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on December 14, 2022. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

energiesnet 12 19 2022