Max De Haldevang, Bloomberg

MEXICO CITY

EnergiesNet.com 06 27 2022

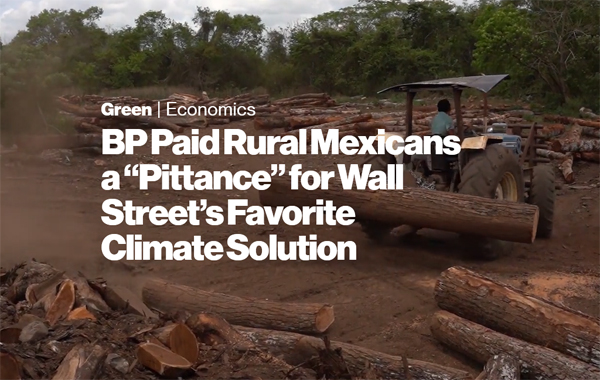

In the coldest months of the year, thick fog blankets the mountain village of Coatitila in eastern Mexico, hiding the bulging, pine-covered hills that cradle it. At midday, the sun pulls back the fog to expose patches of blight where trees have been axed for logging or farm work.

In 2019, Coatitila’s leaders thought they’d found a way to protect the dwindling forests and bring a serious change to a local economy where the average person earns only $6.40 a day when they can find work. One of the world’s most prestigious climate nonprofits, the World Resources Institute, was helping run a program that pays villages to reforest their communally owned woods and improve forestry management. Participation would bring in cash from oil giant BP Plc, which would ultimately purchase carbon credits that the villagers generated, along with further funding from a US government agency.

After two years of work, the village got its first annual payment in late 2021. The pay, split among 133 members of the community, amounted to about $40 each, a fraction of what the village’s then-leader, Álvaro Tepetla, expected. He’d hoped they could earn as much as $44,000 in total per year, or at least match the $8,100 paid by a recently canceled government conservation program. The final sum was 30% lower and worth little more than a week’s work per person.

The program is funded using carbon offsets, a financial tool that aims to fight climate change by turning carbon dioxide captured by protecting trees into a valuable commodity. Each offset should equal a ton of carbon absorbed thanks to changes driven by the promise of payment. BP, as the buyer of the credits, would be rewarding the community for its care for forests while acquiring an asset that could be held as an investment or sold to third parties and used to write off corporate carbon emissions.

BP has found a carbon bargain in some of Mexico’s poorest areas. In more than a dozen places identified by Bloomberg Green, the oil company has bought offsets at an enormous discount, according to interviews with 18 people across three states and Mexico City who have been involved in the program or approached to join it. By paying $4 per offset to subsistence farmers in remote areas with less access to education and internet, BP has handed over around 15% of what others are now offering for offsets from Mexican projects. Facilitating the program has been WRI, one of the most trusted names in climate work.

After learning about the pay disparity from Bloomberg Green’s reporting, community members in Coatitila say they confronted one of WRI’s local contractors. Weeks later the contractor told the village that BP had agreed to increase their pay. Kathy Gregoire, executive director of leading Mexican environmental nonprofit Pronatura México AC, which administers the project, says following negotiations, BP has committed to paying a floating amount based on market price, but she didn’t provide further details.

Most community leaders interviewed for this story didn’t realize how much offsets fetch on the market, or that the ultimate buyer of their offsets was BP. “It’s pretty unjust,” says Tepetla, a muscular 45-year-old, standing outside his two-room wooden house, the dramatic mountain backdrop peeking through the fog. “You only find out about all this afterwards.”

The project, named CO₂munitario, spans 59 communities in more than a half-dozen states and covers around 200,000 hectares of land. BP put forward $2.5 million to start the program in 2019, which was matched by USAID, the US government’s development arm. In 2021 the oil giant inked a deal with Pronatura to buy as many as 1.5 million offsets at $4 each.

The price is a “rip-off,” says Benjamin Rontard, a climate researcher in central Mexico who wrote his doctoral thesis on Mexico’s carbon market at the Autonomous University of San Luis Potosí. They’re taking advantage of “campesinos who don’t have any other option for economic activity.”

“BP’s goal as a partner in the CO₂munitario program is to generate new opportunities in the Mexican voluntary carbon market, protect standing forests in Mexico, and support sustainable development opportunities for local communities,” the company said in a statement. “We aim to create conditions that help landowners generate revenue from the protection, restoration, and sustainable management of forests.”

Offsets are a source of constant controversy in climate circles, as programs often fail to deliver the climate benefits they promise while allowing polluters to keep burning fossil fuels. BP’s Mexican projects don’t appear to have the same glaring climate issues as other programs. Instead, the offsets that BP purchases expose another failing in the nascent market: A lack of oversight can leave people already in poverty ripe for exploitation—now in the name of climate progress.

The offset market, where traders buy and sell Wall Street’s favorite climate solution, surged to $1 billion last year, but doubts about offset projects’ legitimacy have plunged the future of the new commodity into uncertainty. A major US offset supplier told Bloomberg Green that most projects, including some of his own, are shortchanging the climate. An Australian ex-official described projects there as “largely a sham.” BloombergNEF, a clean energy research group, says the market could either skyrocket past $100 billion or crumble without improvements in quality.

The potential for enormous scale has drawn many leading lights in the climate world to carbon offsets. Perhaps none are more crucial to the climate establishment than WRI, a widely respected nonprofit in Washington that’s drawn up best-practice guidelines on offsets. The group now says villagers deserve better payment for the offsets it helped create for BP.

“We know and acknowledge it’s a low price,” says Javier Warman, WRI Mexico’s Forest Director, in an interview. When the project started, he says, “nothing was moving and there was no demand, so for the communities, this decision of going with $4 was better than nothing.”

WRI, Pronatura, and USAID say they see the venture as a way of driving real development in rural economies and protecting Mexico’s heavily endangered forests. WRI and Pronatura said discussions about financial inequality at the COP26 climate summit last November also inspired them to renegotiate with BP.

Most village leaders hadn’t known about the disparity between their paycheck and the price credits fetch on the market. But none were surprised by the power dynamic at play. “People treat Mexicans as they see us—as people who aren’t good for anything, who aren’t worth anything,” says Vicente Martínez, leader of Lázaro Cárdenas Número 2, deep in the southeastern jungle of Campeche.

Manuel Nah, a leader in nearby village 20 de Noviembre, echoes this sentiment: “All of history has been exploiting poorer countries.”

Regarding corporate behavior around global warming, WRI has enormous influence. The group helped develop voluntary industry standards that now underpin all company reporting on emissions through the Greenhouse Gas Protocol, which large businesses around the world have widely adopted. It also informally polices corporate climate plans through The Science Based Targets initiative, a kind of watchdog that can award or withhold its seal of approval. In both cases WRI acts as a funder and has officials who help shape outcomes.

WRI has little direct experience running offset programs. Its usual role is counseling groups active in the offsets market and suggesting best practices in a burgeoning industry with few established norms. There are WRI-penned guidelines for companies looking at using forestry programs, for instance, that admonish would-be buyers to first “build confidence that they are doing all that they can to abate their own emissions now and in the future” before purchasing offsets.

That advice, published last year, creates a clear standard: Before buying offsets, a company should maximize cuts to its greenhouse gas emissions. For observers such as Charlie Donovan, a former BP executive who now teaches sustainable finance at the University of Washington, developing offset projects is “an inherent conflict of interest” for a standard-setting organization such as WRI. “You can’t be a fox and a hen at the same time.”

Warman of WRI says the organization joined the Mexican project because there “wasn’t anything happening” in the local market and they saw the funding as an opportunity to “light up the process.” WRI calculated their training and capacity building as worth $3.50 per credit to the villagers on top of the $4 in cash, whereas Pronatura valued it at $2. Starting in late 2024 those communities will be free to sell to the market directly, Warman adds, and WRI will help ensure communities get a fair deal.

At the time the contract was signed in 2021, there wasn’t a widely accepted average price for carbon offset projects. BloombergNEF estimates that the average cost of nature-based offsets was $5.60 per ton in 2020 and $4.73 per ton in 2021, but prices vary wildly according to geography and the type and quality of the projects. ICICO, a nonprofit with several long-running offset projects operating in Oaxaca, earned an average of $9.75 from 2019 to 2020, its international coordinator, Rosendo Perez, says. Latin American e-commerce giant MercadoLibre, Inc. announced the upfront funding of a project this year where it expects its investment to be worth an average of $24 to $34 per offset, depending on performance.

Pronatura’s Gregoire says they landed on the $4 figure by looking in 2019 at carbon tax prices, which she says seemed between $2.50 and $3.50.

WRI’s own research shows villagers have been vastly underpaid. Global buyers are willing to pay at least $7 premium for forest-based offers, plus another $2.30 to support poor communities, according to the abstract of a study co-produced for the project by WRI. That total is more than double the $4 price BP has paid.

WRI has a policy of not working with oil companies, so Pronatura handles communication with BP. Warman acknowledged it’s a “slippery slope” to work on a forestry project whose buyer is a major polluter, and that perhaps “there will be some learnings” for the organization on that front.

BP holds itself at the vanguard of oil companies seeking to transition to a green economy, saying that by 2030 it aims “to be a different kind of energy company” and committing to net-zero emissions by 2050 across operations, production, and sales.

BP Chief Executive Officer Bernard Looney has been front and center of this drive, talking up the need for a “just transition.” That process is supposed to lift everyone: “We must ensure that workers and communities do not lose out as we strive to help our planet. We must take everyone with us,” Looney said last year. “We want a transition that ensures no one is left behind.”

As well as a righteous talking point, it would be a sound strategy. Paying low prices for carbon credits can end up undermining a project’s chances of effectively fighting climate change. For forestry offsets to work, the University of Washington’s Donovan warns, the woods need to be protected for decades—and that means locals need to earn enough to stop them from ever chopping down trees for farmland.

“Four dollars per ton doesn’t even begin to cover a real lasting change on how land is used,” Donovan says. “I’ve never seen an instance where $4 per ton was enough to move the needle.” USAID and WRI say BP’s improved payment system will help ensure the project’s longevity.

BP spotted opportunities for cheap Mexican offsets as far back as 2018. During a scouting expedition, company officials visited offset projects run by ICICO in Oaxaca. The oil giant had a price in mind: $2.50 to $3 per offset.

Perez, ICICO’s international coordinator, was willing to work with BP despite what he now calls “really quite abusive” prices because there was very little funding available at the time. BP ultimately chose a partnership with WRI and Pronatura, leaving Perez to watch as dozens of communities signed up. Perez says BP was able to pay low prices because of the lack of other investment options.

The resulting structure put layers between the Mexican villagers and the oil giant. Pronatura prepares reports and coordinates funding. WRI tends to manage the projects more directly, subcontracting and training villagers and local forestry companies to do the technical work. BP and USAID split the cost of setting up the project.

The communities that joined earlier such as Coatitila and others in the mountains of Veracruz state, spanning hundreds of miles of Mexico’s Gulf Coast, have started receiving payments. Meanwhile, WRI and Pronatura have set up the next projects in the southeastern rainforests of Campeche, Quintana Roo, and other places. The carbon-credit programs train communities in improved forest management, which can mean selectively cutting down older trees that absorb less carbon to make space for younger ones to grow.

The people of Coatitila first heard about the project from a local forestry expert subcontracted by WRI and Pronatura, who brought her pitch to a meeting in the village hall, says Eusebio Tepetla, Alvaro’s uncle and also a former village leader. “She was talking about carbon offsets but we didn’t know what that was,” Eusebio said.

The community understood they’d be paid for the use of their land and that they’d have to spend a few days a year cutting down trees. The forestry expert was vague about how much they would be paid, Eusebio remembers, saying it depended on which company would buy the offsets. Other villages say they got more information but no scope for negotiation. The community of 20 de Noviembre in Campeche was told it would be $4 per offset. “You take it or leave it,” says Nah, a member of its leadership group.

Like many other village leaders, Álvaro says he believed that the small payment was down to the hefty expenses required to start the program and the need to recoup costs. He didn’t realize USAID was donating as much as half of the startup capital. WRI’s Warman says USAID’s role wasn’t hidden from communities, with the organization regularly participating in briefings.

Communities committed freely to the project and were informed in line with United Nations Indigenous rights principles, including being told that BP was the buyer, John Vance, US Embassy spokesperson in Mexico City, said in a statement. The project has a grievance mechanism and is regularly audited by third parties to guarantee its benefits, he said.

Vance and a WRI spokesperson say their organizations—which weren’t party to the contract with BP—understood that the oil giant had committed to not selling the offsets, instead using them only internally.

But BP says it plans to sell the credits as commodities to clients, because it has committed to not using offsets to meet its end-of-decade emissions targets. It could use the Mexican credits to brand gas as “carbon offset,” as it did with offsets from a Mexican project last year. Pronatura, which signed the contract with BP, says the project did not regulate the company’s use of the offsets.

For now, the oil giant is sitting on a lucrative asset. The average forestry offset on the global market sells for $12 to $16, says Guy Turner, founder of Trove Research, which analyzes carbon markets. That’s as much as quadruple what BP paid the villagers.

A long, potholed drive from the touristy Mayan ruins in the jungle of Campeche leads to the village of Lázaro Cárdenas Número 2. There’s no major industry beyond subsistence farming, and community leader Vicente Martínez is desperate for the payout from BP and WRI that he calls a “pittance.” He left school at age 13, hit the road from his hometown in central Mexico, and sought farm work in the southeast. These days, he says, no one else is making the meandering journey through the rainforest with better economic offers.

In the coming years, “I think there will be a lot of suffering because it’s very little money,” says Martinez, 55, a stocky figure in a white cowboy hat and jeans. But afterwards “we will be free to sell to the best buyer,” he says. “We’re doing this so it will benefit future generations.”

The village’s plans to expand the land under conservation for offsets fell into turmoil once the residents discovered they’d be paid half the $8 per offset they’d expected. They’d earmarked the income to pay for expensive studies to expand the work, but those costs will exceed the roughly 50,000 pesos ($2,548) they now expect from their first annual payment, Martinez says. (WRI’s Warman says he didn’t know how the village came to expect $8 per offset.)

There often isn’t much work in many villages that took up the promise of carbon offsets. If BP were shelling out $16 per credit, the higher end of the average rate on international markets, its yearly payments would be worth more than five weeks’ field labor per community member in a place like Coatitila.

The higher price might keep more young men at home. As it stands, many spend months every year traveling for seasonal labor. For Álvaro Tepetla’s 25-year-old son, a higher payment could have enabled spending more of the year with his young daughter in the village. He’s now living hours away in Oaxaca. Álvaro’s cousin, Braulio, 35, has been picking asparagus during 18-hour shifts without weekends on a farm in Michigan.

Braulio has spent most of his adulthood traveling for work around the US and Mexico. He’s hardly seen his three kids grow up. “It’s horrible,” he says. “You can call them when you have time, but when we get home at night, they’re already asleep.”

Paying market rates would also encourage people to add their privately owned land to the project and provide income to help men such as Braulio spend more time at home, Álvaro says. “More people would work on their forests here,” he says, if the work paid better.

By helping an oil major with a low-paying project, WRI and Pronatura are engaging in a kind of “carbon colonialism,” says Silvia Ribeiro of ETC Group, a nonprofit that studies technology, biodiversity, and poverty. While BP continues to produce fossil fuels and emit carbon, it also wrings valuable commodities from poor communities in a country heavily exposed to risks from climate change.

“Both these organizations are acting not as environmental defenders and defenders of communities,” Ribeiro says. “What they’re doing is making a living off helping polluting companies to justify their” pollution.

Pronatura’s Gregoire acknowledges that it’s a “polemic subject” but says they broker offsets as they see them as a way to create “amazing impact in forestry communities” while the world slowly transitions to renewable energy. Pronatura and WRI are taking the smallest payment possible to try to cover their costs for running the program, she says.

Some communities have started resisting the low compensation for carbon work. In Quintana Roo, near the glistening beaches of the “Mayan Riviera,” some villages have more land, better education, and closer proximity to other economic opportunities—and, therefore, more power. They have had offers from competing organizations and don’t need income badly enough to rush into a deal with rough terms. Some developers take a cut of market rate, whereas others pay a fixed price of around $8 to $12 per offset.

BP’s projects in Campeche and Quintana Roo started later than those in Coatitila and its neighbors in Veracruz state, and the pandemic has also held them up. The program doesn’t push villages to sign a binding contract until shortly before it starts making the payments, villagers said. This gives the communities a potential exit.

Petcacab, an easy drive to the booming resort town of Tulum in Quintana Roo, is the only one of the 10 places Bloomberg Green visited where landowners managed to negotiate with representatives of the program. They first agreed to the usual deal, but they were soon approached with better offers by other organizations, says Celso Chan, who spoke outside the busy timber mill of the furniture company he owns in Petcacab. Using that as leverage, they persuaded the project’s administrators to pay $10 for credits on half of the land, while staying around $4 on the other half, Chan said.

Chan says the village stuck with BP because they felt obliged to keep their word after taking funding to set up the program. He also trusted the well-known multinational BP and the USAID officials he spoke to more than other organizations he hadn’t heard of.

“We have a rule that if we make an agreement, we don’t break it. Other people can come and offer something, but if we have a commitment, we uphold it,” says Chan, 48, who holds a forestry degree and is a member of the village leadership team.

It helps that in Petcacab the money is far from essential. They’re planning on using half of it to fund carbon offset projects they want to run themselves, Chan says, with expertise they’ve gained during the process.

Others with fuller coffers like Nuevo Bécal, Campeche, are developing projects with their own money, said Juan Manuel Herrera, a community member who runs a forestry consultancy. As of May, they were negotiating a loan from a European development bank at 6% to 8% interest to fund the project, which they expect to be able to pay off after one year of selling offsets on the market, Herrera said.

“Since we didn’t get a good agreement with anyone, we’re going alone,” Herrera says. “That way we won’t have an obligation to anyone.”

Another fairly prosperous village, Laguna Om, decided to turn its back on BP. After a few days of training sessions run by the program, village leader Gualberto Caamal Ku says other organizations approached with offers. Members of its leadership team, who’ve worked as teachers and accountants, researched WRI’s program and concluded its terms were an “abuse,” says Caamal, 61, a retired elementary school teacher.

Laguna Om worked out a 10-year deal with Toroto SAPI de CV, a startup social enterprise, which pays 77.5% of whatever offsets sell for on the market. Most of the remainder would go to Toroto, with a 5% fee for local technical experts. “If they want to earn more cash, they should pay more,” Caamal says of BP. “They started their projects first so people accepted” the low price.

Beyond safeguarding the land already committed to offset projects, better pay could greatly expand the area that villagers make available. Álvaro’s eyes widen and a grin reveals smile lines on his youthful face when he talks of what the community would do if offsets provided serious income. Not only would they take greater care of the communally owned forests already part of the program, but village leaders would encourage people to reforest their privately owned land, he says.

“We’d make a group and see if we can enter a program as individual landowners,” he says. “We’d know that we’d be able to eat, thanks to those little trees.” —With Ben Elgin

Editors: Emily Biuso, Aaron Rutkoff, and Sharon Chen

Photo editor: Marie Monteleone

Design and layout: Bernadette Walker

bloomberg.com 06 27 2022