By David Fickling

How will the world’s oil markets cope without China? They may be about to get a foretaste.

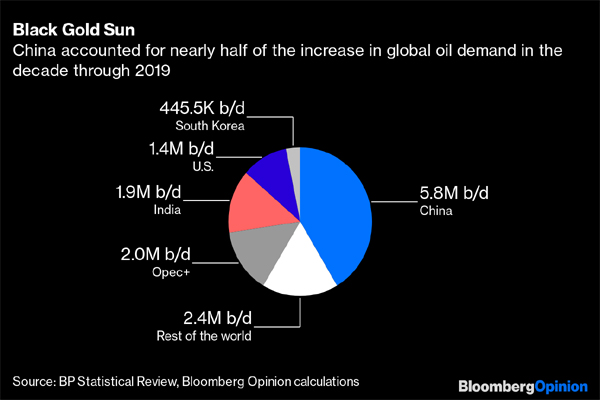

As with every commodity on the planet, Chinese demand has had an overwhelming impact over the past few decades. Consumption as a whole is lower than for some other materials: At about 15% of global demand, the country uses a bit less per person than the world average, compared with its roughly 53% share of the planet’s steel production. Still, in terms of incremental growth, China is everything, accounting for 41% of additional daily barrels pumped between 2009 and 2019.

That’s a problem both for China, and for the planet. Oil accounts for roughly a third of global emissions, second only to coal. But its array of uses in more than a billion engines and chemical plants around the world make it harder to replace than solid fuel, whose use is more centralized. A near-term peak in oil consumption is a prerequisite to avoid devastating climate change.

Even setting climate damage apart, China’s narrowest self-interest points in the same direction. The country depends on imports for 73% of its crude. In the best of times, that was a security risk necessitating pipelines through Myanmar and Siberia, naval activity in the Indian Ocean, and island-building in the South China Sea. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, and the response from the U.S., Europe, Japan and their allies, makes that risk a lot more real. Were Beijing to make good on its threats to invade Taiwan, it could face not just the economic embargo that Russia is struggling with — it could be cut off from supplies of the energy it needs to power its war machine and the wider economy.

The expectation of slumping demand this week, as Covid-19 prompted lockdowns in Shanghai and an estimated 200,000 barrel-a-day reduction in consumption, has given the world a small flavor of what this might look like. Brent crude crashed 6.8% Monday, its sharpest daily drop in nearly three weeks, before slipping further Tuesday.

It would be a mistake to see this pause in China’s voracious oil thirst as a one-time effect of the pandemic. “Energy security” was one of the main themes of Beijing’s 14th Five-Year Plan for energy released last week, along with “efficiency.” The former term encompasses both the prevention of blackouts like those suffered across the country last autumn, and reducing China’s heavy dependence on imported petroleum.

Shrinking that bill won’t be easy. China’s domestic oilfields appear to have hit a point of diminishing returns. State-owned oil companies have been spending heroic amounts lately — PetroChina Co. last year dedicated more to capital expenditures than Saudi Arabian Oil Co., and the country’s biggest refiner China Petroleum & Chemical Corp. this week promised to increase capex to a record 198 billion yuan ($31 billion), with oil drilling taking up a rising share of the total. Yet production from all that spending has crept up only modestly, and the target of 200 million metric tons of production in 2025 would essentially see the country hold steady at current levels.

That leaves only one option if China is serious about reducing its dependence on imported fuel: thrift.

There’s plenty to be done on that front. The oil intensity of China’s economy — the amount of crude it takes to generate $1,000 of output — is notably high for a densely populated country at the mercy of imports, at about 0.22 barrels in 2019. That figure has improved only gradually over the past decade, with even the U.S. and Russia reducing their thirst at a faster pace. If China can match western Europe’s recent levels of around 4% annual improvement in oil intensity, however, it could grow its economy at 5% a year throughout the next decade without appreciably adding to oil demand.

Beijing needs to raise its ambitions. The Five-Year Plan promises that electric vehicles will hit 20% of car sales by 2025, but they’re already likely to exceed a quarter of China’s passenger car market this year. Sinopec expects refining capacity to hit a cap of one billion tons in the same year, enough to push the country’s import dependence even higher, given the relatively modest targets for domestic oil production.

At current volumes and the forecast annual average price of $103 a barrel for this year, oil is already likely to be China’s biggest import this year, worth $389 billion and exceeding even computer chips. Its vast and secretive petroleum reserves, which have sucked up extra barrels for years, now appear to be more or less full.

Ending this addiction should be a priority. China’s voracious appetite for crude isn’t just a threat to the planet — it’s a risk for a government whose legitimacy depends on economic growth that’s still far too leveraged to foreign oil. Those expecting insatiable Chinese demand to pump up consumption the way it did over the past decade should take heed.

This column does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners.

_______________________________________________

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on March 29, 2022. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

bloomberg.com 03 31 2022