Maria Eloisa Capurro, Bloomberg News

PANAMA City

EnegiesNet.com 08 16 2022

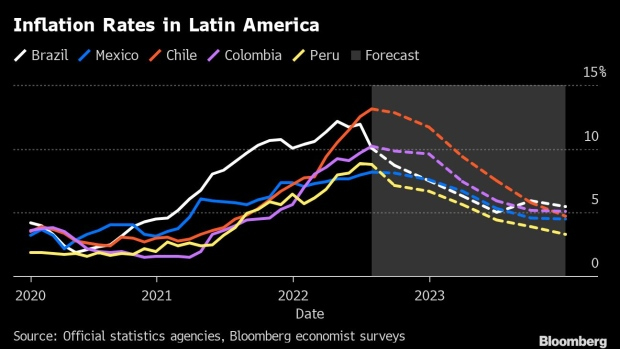

In the fight against pandemic inflation, Latin America led the world into a new age of tight money. Eighteen months later, there’s not much sign that being first in will help the region to become first out.

On Thursday, the central banks of Mexico and Peru announced what were respectively their 10th and 13th consecutive interest-rate increases. Forecaster don’t think either of them is done yet. In Brazil, one of the world’s first hikers back in March 2021, there’s some prospect of a halt. Still, policy makers said this week they expect to keep rates in “significantly contractionary territory for a sufficiently extended period.”

Latin America’s central bankers aren’t of course the only ones to miss their targets by a mile during the worst price shock in decades. But, amid signs that the inflationary wave may be cresting, they have particular reason to stay alert.

A local history of hyperinflation means even simple contracts like rents are linked to past price rises, helping inflation get baked in. Governments have rolled out plans for more spending — to shore up economic recoveries, boost their election prospects or alleviate inequality –- pushing in the opposite direction to central-bank policies that are trying to rein in demand.

‘Have to Wait’

And on top of that, the region’s currencies -– mostly solid performers this year, thanks to high rates and commodity prices -– have been looking wobbly again in recent weeks.

What Bloomberg Economics Says…

“Inflation resilience reflects the delay between the rate hikes and their effect on the economy. Those effects are hindered by two other factors: the adverse external scenario, that weakens emerging currencies and pushes tradable prices up; also, the fiscal measures adopted by some Latin economies fuel the very inflation whose effects they intend to soothe.”

–Adriana Dupita, Latin America economist

Currency slumps, especially when the US and other developed economies are raising their own interest rates, are a classic path to runaway prices in Latin America. That gives central bankers another incentive to keep policy tight –- and perhaps use other tools, too. Chile intervened in foreign-exchange markets last month, and others may follow suit.

“There’s a chance many will have to wait until 2024 to cut rates,” says Gabriel Casillas, head of economics for Latin America at Barclays Plc. Economists surveyed by Bloomberg suggest easing could begin a bit earlier than that — but still not before the second half of next year.

Inflation is still accelerating in many Latin American nations, with Mexico and Chile recently posting multidecade highs. In Argentina, which has endured two decades of wild economic swings, it’s soared past 70% — prompting the central bank to jack up interest rates by almost 10 percentage points on Thursday. Overall, the region has the world’s fastest price-growth outside of war-torn Eastern Europe, data compiled by Bloomberg show.

Brazil did see a sharp drop in prices last month, though it was largely due to energy-tax cuts pushed by President Jair Bolsonaro, who’s up for re-election in October.

Still, economists say the monetary medicine is having some effect.

Andre Loes, head of economics for Latin America at Morgan Stanley, estimates that inflation would likely be as much as three percentage points higher if policy makers hadn’t moved as early as they did. And while inflation expectations are now running well above central bank targets, Loes says they could fall back rapidly if the recent decline in commodity prices is sustained.

‘People Will Press’

That wouldn’t be good news for economic growth, though.

Soaring prices for the region’s exports, from food to minerals and metals, have contributed to what analysts at Goldman Sachs Group Inc. called “remarkably resilient” output this year. It’s allowing governments to use their budgets to shield the public from the impact of inflation.

In Brazil, rebounding tax revenue has helped Bolsonaro cut taxes and boost social spending ahead of elections. Mexico says higher oil earnings will finance $28 billion in subsidies this year. Chile has announced a new round of social aid, and Colombia’s new government pledged to increase public spending.

Such measures can lower prices in the short run, like they did in Brazil last month. But by propping up consumer demand, they also mean broader inflationary pressures may stick around for longer. That makes it harder for hawkish central banks to reverse course even when growth stalls, as it’s forecast to do across the region in the coming year.

“As soon as the economy slows down, people will press for that support, and very likely politicians are going to deliver,” says Mario Castro, a rates strategist at Banco Bilbao Vizcaya Argentaria SA in New York. “If you have a more expansive fiscal policy, your ability to cut rates is diminished.”

‘Part of the Tool-Set’

Latin America’s currencies are also at risk from an end to the pandemic commodities boom, as well as US interest-rate hikes that are set to continue well into 2023.

For most of the year, they’ve held up better than most against the surging dollar. Brazil’s real and Mexico’s peso are among a handful of currencies to post gains, though they’ve lost ground from mid-year highs.

Others have seen a steeper slide. Chile’s central bank reversed a rout in the peso in mid-July by announcing it would spend $25 billion over several weeks to buy it.

With interest rates already high enough to threaten economic growth, and many Latin American countries holding ample amounts of foreign currency, other central banks may turn to such measures as part of the fight against inflation, says Daniel Titelman of the Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean.

“We’ve seen big enough depreciations, in a region that has generally speaking accumulated reserves,” he says. “That’s part of the tool-set you have, the same way as Chile did.”

bloomberg.com 08 15 12 2022