After surviving attempts to oust him over an allegedly rigged 2018 presidential election, the authoritarian leader is turning global political and economic events to his favor.

By John Polga-Hecimovich

fragile economic recovery and shifting geopolitics have bolstered Venezuelan President Nicolas Maduro while creating more favorable conditions for negotiations involving the United States and his domestic political opponents. Strategies for challenging the authoritarian leader have also changed. In contrast to previous maximalist demands, Washington and some Venezuelan opposition and civil society groups are pursuing incremental change, a strategy that holds a greater chance of success. Nonetheless, political liberalization in the form of free and fair elections still appears to be a remote possibility.

Market liberalization and economic recovery

After a seven-year recession amid U.S. sanctions, Venezuela’s economy is projected to grow nearly 8 percent or more in 2022. Hyperinflation has ended, oil production and economic activity have increased, and there is a greater supply of goods in stores.

Although inflation remains among the highest in the world, the country broke out of a four-year bout of hyperinflation as the government slowed the pace of printing money and the U.S. dollar became the preferred currency. Annual inflation decreased from thousands of percent to 686 percent in 2021 and is estimated to be around 90 percent in 2022. At the same time, the country has managed to double its petroleum production over the last two years to around 700,000 barrels per day, while international oil prices have soared in 2022. Consumers are enjoying fewer queues to buy products and greater availability of those products, a far cry from the scarcity of the previous five years. Some foreign airlines – the number of which present in the country decreased from 25 to five between 2014 and 2022 – have even returned.

A break from socialist economic policies explains some of these gains. Among other changes, President Maduro has initiated limited economic measures to acquire capital and blunt the impact of international sanctions, including a turn toward free markets and currency reforms aimed at encouraging U.S. dollar transactions. The government also announced a series of foreign investment initiatives in state enterprises. In May, Mr. Maduro said that the government would float shares worth up to 10 percent of several state-owned oil, gas, telecommunications and chemical companies on the Venezuelan stock exchange. A month later, Vice President Delcy Rodriguez announced that the state-owned bank Banco de Venezuela (BDV) would sell shares worth 5 percent of the company’s value.

Structural economic weaknesses remain, including in such key sectors as manufacturing, agriculture and financial services.

Undoubtedly, economic stabilization has strengthened the position of the governing regime, which is enjoying what the political analyst Guillermo Aveledo has called the Pax Bodegonica (Bodegonic Peace): an uneasy political calm characterized by formal and informal liberalization of the economy, a reduction in public spending, and an improvement in the supply of products.

It must be noted, however, that these gains pale in comparison to how much the economy contracted from 2013-2020 – an estimated 75 percent or more. Consequently, many Venezuelans have bristled at the idea that Venezuela se arreglo (Venezuela has been fixed), a phrase recently making the rounds on social media, pointing out that any improvement is meager compared to an unprecedented economic depression.

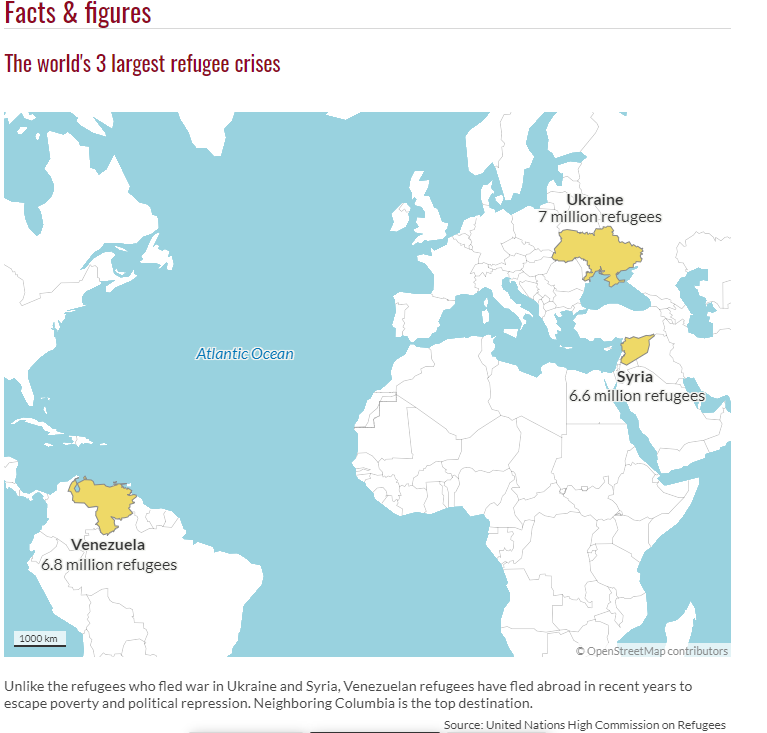

Structural economic weaknesses remain, including in such key sectors as manufacturing, agriculture and financial services. The nation is plagued by high unemployment and stagnant wages. Equally worrying, growth in Venezuela’s economic activities and consumption has been driven in part by illegal activities. According to Transparency International and Ecoanalitica, an estimated 21 percent of Venezuela’s 2021 gross domestic product (GDP) was illicit, including narcotics, gold and gasoline trafficking, and smuggling through the ports. Adding to this, the country’s humanitarian crisis and political repression continue unabated. The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) estimates that 6.8 million Venezuelans – nearly 25 percent of the population – are living abroad as refugees, escaping poverty and political chaos. Neighboring Colombia is the top destination.

In short, a robust economic recovery is probably not on the horizon, despite the rosy predictions for 2022 and 2023

Geopolitical gains

Outside shocks have also changed the balance of power in domestic politics and strengthened the Maduro regime. The first of these is Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, which created incentives for dialogue between the U.S. and Venezuela. Early speculation was that the Biden administration’s decision to ban imports of Russian oil and gas in retaliation for its assault on Ukraine would push the U.S. to seek alternative sources. However, Venezuela’s low output (between 600,000 and 750,000 barrels per day in 2022) and aging infrastructure make it an unlikely candidate to cover any gap in U.S. supply. More importantly, Venezuela remains a key Russian ally in Latin America, and American engagement with Caracas may be an attempt to blunt Moscow’s influence.

Leftist presidential victories in Latin America have also aided the Maduro regime. Argentina and Mexico have been unwilling to criticize the abuses or authoritarianism of the Venezuelan government, while Chilean President Gabriel Boric, who is preoccupied with domestic issues, counts the Communist Party of Chile in his coalition and has offered only muted disapproval. In Colombia, a longtime ally of the United States, the Gustavo Petro government has agreed with Mr. Maduro to resume diplomatic ties that had remained dormant under the previous administration of Ivan Duque. Additionally, a Lula da Silva presidency in Brazil would likely resume normal diplomatic relations with its northern neighbor.

Of these, Mr. Petro’s election especially reduces U.S. leverage over Venezuela and strengthens the current regime. More broadly, though, the U.S. is increasingly isolated in recognizing Juan Guaido as the de facto leader of Venezuela after the alleged fraud that allowed Mr. Maduro to falsify victory in the 2018 presidential election.

Change in opposition strategy

The opposition coalition, known as the Unitary Platform (Plataforma Unitaria), recognizes these economic and international changes and has begun to modify its message accordingly. After its failure to remove Mr. Maduro from power in 2019 and 2020, leadership has largely dropped the refrain el cese de la usurpacion, un gobierno de transicion y elecciones libres (the cessation of the usurpation, a transitional government and free elections). In its place, the coalition has shifted to a less ambitious strategy aimed at co-governance and gradual political liberalization rather than an absolute change in power. Priorities have also moved toward humanitarian relief.

The most likely scenario in the next 12-18 months is that negotiations result in limited concessions from the government.

In doing so, the time horizon for change has also lengthened. Some politicians and activists are intent on fighting for free and fair elections in the 2024 presidential contest, while others are focused on creating a broad alliance to fight other limits imposed by the government. To unify its fragmented membership, the opposition platform announced in May 2022 that it would hold primary elections next year to choose a candidate for the 2024 presidential election. This would mark the coalition’s first primary in more than a decade. Still, to expect free elections in 2024 or even the 2025 regional and local elections may be unrealistic.

Participation is no guarantee of success. Although the opposition competed in the November 2021 regional elections, Mr. Maduro’s United Socialist Party of Venezuela (PSUV) enjoyed gains across the board, enabling the ruling party to claim a sheen of electoral legitimacy. This is the party founded by Hugo Chavez, president from 1999 until his death in 2013.

Detente and negotiations

This combination of international and domestic changes has contributed to renewed talks between the U.S. and Venezuela.

U.S. delegations visited Caracas in both March and June 2022 to confer directly with the Venezuelan government. The first trip marked the highest-level visit by American officials to Caracas in five years. The meeting, which reportedly involved the possible easing of sanctions on Venezuelan oil, brought some immediate results: Chevron was permitted to enter direct negotiations with the Maduro administration on possible future oil operations, the Venezuelan government released two U.S. citizens held in captivity, and the heads of the government and opposition negotiating teams tweeted a photo of themselves shaking hands. The U.S. government did not publicly comment on the second trip, aimed at securing the release of detained American citizens, but it is likely the two sides discussed sanctions and talks between the government and opposition, which the government had suspended in October 2021.

In one respect, these discussions further weaken the position of Mr. Guaido, the opposition leader. Although the U.S. officially recognizes him as interim president of the country, its ongoing negotiations with Mr. Maduro demonstrate an implicit recognition of the Venezuelan leader’s power.

Scenarios

President Maduro as is strong as ever, which suggests three trajectories for negotiations.

Limited easing of sanctions

The most likely scenario in the next 12-18 months is that negotiations result in limited concessions from the government. The government wants sanctions lifted but can continue to scrape by even with them in place – especially if energy prices remain high. In this scenario, some sanctions and trade restrictions would be relaxed as a prerequisite for releasing political prisoners, allowing humanitarian aid to enter the country (e.g., World Food Programme and United Nations involvement), and permitting foreign financing to ease the electricity crisis. Chevron would be granted a license and enter negotiations with the Maduro administration, although it will not be authorized to drill or export Venezuelan oil.

Full easing of sanctions

A less likely scenario is one in which the U.S. government fully eases sanctions and the Maduro regime capitulates on significant issues of contention with the U.S. and the democratic opposition. U.S. National Security Council Senior Director for Western Hemisphere Affairs Juan Gonzalez has reiterated that the U.S. would only consider taking such measures if granted significant concessions from the Maduro administration. This would be conditional, for example, on the release of more U.S. citizens held by the regime and on broader commitments by Mr. Maduro – not only to resume negotiations with the opposition but to show progress toward free and fair elections.

This is certainly a possibility, but less likely given the government’s strengthened position. However, if it were to occur, multiple actors would benefit, depending on the degree of concessions granted: the Venezuelan people would enjoy humanitarian relief, the Venezuelan government would avoid having to scramble around sanctions, and the U.S. would be able to count on Venezuelan oil.

A normalization of commercial relations would encourage Venezuelan oil imports to U.S. refineries. In this scenario, Chevron would take operational control of their four joint ventures in the country alongside Venezuela’s state-owned oil company Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). Although much of the revenue would go to pay the government’s $1 billion debt to the company, royalties are currently at 33 percent. This would provide the government with more resources, including those for infrastructure and food.

Regime breakdown

The least likely outcome is regime collapse and restoration of democracy, regardless of the state of international sanctions. President Maduro barely survived threats to his rule in 2019 and 2020 and has ably coup-proofed his administration through a combination of repression and clientelism. Modest economic liberalization has given him more breathing room. Continued international sanctions on Russian oil and gas and high global energy prices will only help further fortify the regime. There is also less regional pressure on Mr. Maduro now than at any point since he came to power in 2013, and there are hints of a normalization of relations coming from Europe as well.

As a result, both the democratic opposition as well as the U.S. will find that international pressure on the regime is no longer a plausible option. That will reinforce the incremental approach they have now adopted, and scuttles the likelihood of a major political breakthrough, such as clean elections by 2024.

______________________________________________________________

Dr. John Polga-Hecimovich is a political science lecturer and researcher, with a focus on governance, democratic institutions and stability in Latin America. Currently, he is an associate professor of Political Science at the U.S. Naval Academy and an associate researcher at FLACSO-Ecuador. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Geopolitical Intelligence Services (GIS), on September 14, 2021. All comments posted and published on Petroleumworld, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

EnergiesNet.com 19 09 2022