By Javier Blas

Chevron agreed to buy Hess for $53 billion not long after Exxon paid $59.5 billion for Pioneer. Both deals are paradigmatic of a larger trend.

Every M&A deal has two sides, with equally powerful motivations. In the oil industry, the incentive for ExxonMobil Corp. and Chevron Corp. — both of which have announced deals this month worth more than $100 billion together — is clear: They want to future-proof their businesses. But why sellers are selling, why right now, and why at current prices is far less obvious.

Sure enough, the sellers are signing to all-stock deals when their shares are trading at, or near, an all-time high. By doing so, they are locking in a rich valuation, and they have the option to share any future upside in the share price of the buyer. But that comes with a significant cost: They are accepting minuscule premiums to their stock valuation. Pioneer Natural Resources Co. settled for just a 9% premium when it sold to Exxon on Oct. 11. Hess Corp. accepted a 10% premium from Chevron on Monday.

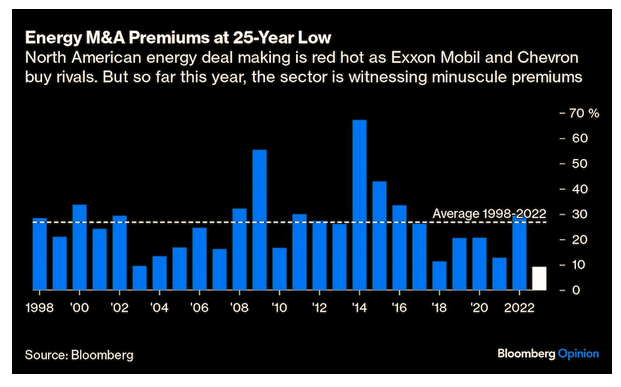

Both deals reflect a broader trend. The North American energy sector has seen $270 billion worth of M&A deals year-to-date, with the average share premium at a 25-year low of just above 9%, according to data compiled by Bloomberg. Between 1998 and 2022, the average premium was about 26.5%.

Ten days ago, I asked Scott Sheffield, the boss of Pioneer, why he was selling. He deflected the question: He wasn’t selling but joining Exxon, he argued. John Hess, the chief executive officer of Hess, had a similar argument on Monday during a conference call with investors. “Our shares have gone up quite a bit,” he said. “We have locked in the value we created, and we can participate in the upside.”

Hess, the son of company founder Leon Hess, isn’t wrong. And “quite a bit” is an understatement: Hess shares are up 161% over the last five years, trading at a price-to-earnings ratio of about 20 times, almost double that of Chevron.

But there’s more to it. Both Pioneer and Hess appear to be aware of the limits of keeping their exploration-and-production oil model in the public market.

For years, E&P companies were all about growth, often at the cost of profits. They still commanded rich valuations as investors hoped for a jackpot from drilling for oil, as Hess did in Guyana and Pioneer did in the Permian Basin. But over the last five years, investors have shifted their interest from growth to profits. E&P companies ditched their old model and reinvented themselves as yield plays, promising dividends and buybacks. The shift may have pleased some investors, but it didn’t meaningfully improve the sector’s overall valuation.

Ultimately, where growth and yield didn’t work, Sheffield and Hess are trying a third way: Sell and fold their business into a larger, diversified and integrated energy company.

It makes sense. Exxon and Chevron could appeal to more long-term investors thanks to their exposure to multiple geographies and their oil well-to-gas pump integrated model, which includes refineries, chemical plants and trading. Their stronger balance sheets, which allow for a lot of debt raising, also offer insulation to the cyclicality of oil prices, guaranteeing fat dividends.

The problem for everyone else in the E&P industry — above all, the US shale industry — is that there are few large buyers left. Exxon and Chevron now have their hands full digesting Pioneer and Hess. Shell Plc CEO Wael Sawan would be a natural buyer, but last week he promised shareholders he planned to be “boring” when it comes to deals in 2024. In other circumstances, BP Plc could be a buyer too, but the British major lacks a permanent CEO. Among Big Oil, that leaves TotalEnergies SE as the only potential buyer in the near future. I doubt national oil companies in the Middle East would venture into the E&P space in any major way.

In a consolidating industry, one wants to sell early before the best buyers have satiated their appetite elsewhere. With Exxon and Chevron done, many US shale companies face the prospect of having to consolidate among themselves to create firms that could appeal to long-term investors. Intra-shale M&A would follow. Don’t expect any more of a deal-making premium when that happens.

____________________________________________________

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He previously was commodities editor at the Financial Times and is the coauthor of “The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources.” @JavierBlas. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on October 23, 2023. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

EnergiesNet.com 10 23 2023