- State oil driller has $105 billion in financial obligations

- Investors weigh odds of new issuance, other financing options

Amy Stillman and Maria Elena Vizcaino, Bloomberg News

MEXICO CITY

EnergiesNet.com 01 09 2023

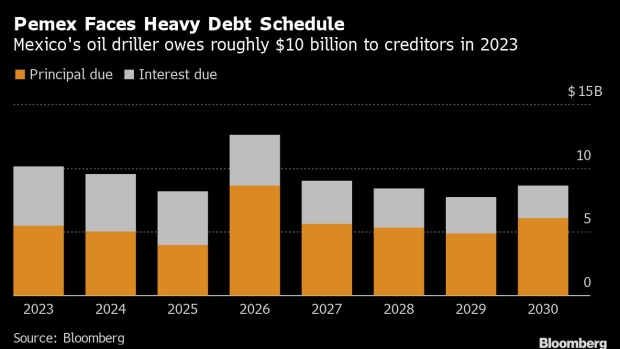

Mexico’s debt-laden oil driller, Petroleos Mexicanos, is searching for funds to make almost $10 billion in bond payments this year — a sum that neither the company nor the government included in their annual budgets.

While President Andres Manuel Lopez Obrador promises his government would step in to help the company if necessary, the Finance Ministry expects Pemex to foot the bill in the first quarter. After providing the driller with financial support in recent years through tax breaks and capital injections, it stopped covering Pemex’s debt amortizations in the second half of 2022.

That’s led investors to question whether the energy giant will tap international markets, try selling unpaid oil-product invoices or find other ways to secure financing.

“It’s become clear that under this administration, there will be no major Pemex bailout,” said Roger Horn a senior strategist at SMBC Nikko Securities America in New York. Large asset sales akin to Brazil’s stripping of state-owned Petroleo Brasileiro SA also seem unlikely, he added.

The company did not immediately respond to request for comment.

The nation’s coffers have been strained by the president’s social programs and over-budget major public infrastructure projects, such as the Dos Bocas refinery and Maya train, which are more than double their original price tag.

Oil income has also fallen as a percentage of federal revenue as a result of long-term production declines and a reduction in Pemex’s profit-sharing duty.

Pemex has laid out plans to try and avoid tapping markets in a bid to maintain its debt level at about $105 billion through 2027 by seeking “discreet, innovative” financing alternatives. International debt markets have gotten far more expensive due to the Federal Reserve’s aggressive monetary tightening, especially for junk-rated borrowers such as Pemex.

The company’s most-recent debt maneuver in June — which paid oil suppliers with notes to be exchanged later — was deemed a flop due to weak demand.

The oil major also raised cash last year by selling unpaid invoices for oil and oil products to banks, known as monetizing receivables with factoring. In the second half of 2022, HSBC and Goldman Sachs Group Inc. gave Pemex at least $1 billion in a deal connected to it selling receivables. HSBC also tied it to Pemex reducing greenhouse gas emissions.

Yet these financing solutions may not be enough. Pemex has amortizations of between $5.5 billion and $6 billion in the first quarter alone, Chief Executive Officer Octavio Romero said, and it owes as much as 188 billion pesos ($9.8 billion) this year.

Patrik Kauffman, an investor at Aquila Asset Management in Zurich, said the company could seek financing by doing a liability management exercise or a receivables-backed issuance.

“It depends very much on the rate they need to pay,” he said. “And if too high, the government is there and said it clearly. I believe the most viable way is the government.”

If forced, the beleaguered company may tap into its 2023 budget to pay down debts, a move that would further strain its struggling oil operations. Pemex’s oil production has fallen almost every year since 2004, and the company has failed to develop big discoveries to replace older mega-fields. Under AMLO, Pemex has focused on boosting output in its aging, unprofitable refineries rather than higher-value drilling.

Such operational inefficiencies caused the driller to lose billions in the third quarter, even as surging oil prices helped international rivals to amass record profits.

Even so, Wall Street has found opportunity in the company’s high-yielding debt because of its ties to the government. Pemex’s notes due in 2028 yield about 4 percentage points more than Mexican government bonds with the same maturity.

“At the end of the day, it’s the same entity,” said Ray Zucaro, an investor at RVX Asset Management in Miami, which is overweight on the debt. “It’s 100% owned by the sovereign.”

bloomberg.com 01 09 2023