Inventories in Cushing, Oklahoma, the “pipeline crossroads of the world,” are falling to dramatically low levels.

By Javier Blass

To understand what’s going on in the oil market, you can look at global supply-and-demand — big picture stuff like Saudi production and Chinese consumption. Alternatively, you can examine the small town of Cushing, Oklahoma, population 8,327.

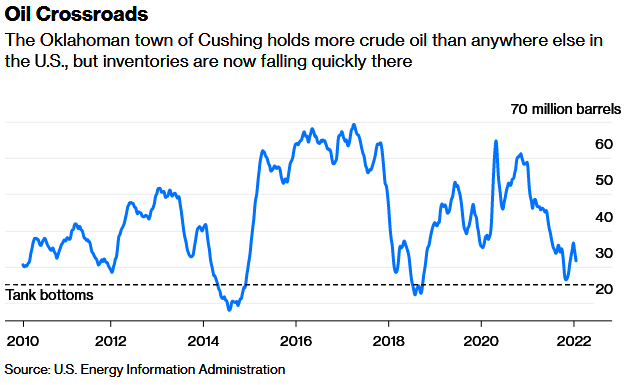

Cushing calls itself the “pipeline crossroads of the world,” where traders of West Texas intermediate (WTI) oil store their barrels in dozens of tank farms spread on the town’s outskirts. These can hold 76.6 million barrels or nearly 15% of U.S. oil storage capacity. Right now, the Cushing market is flashing red — as in red hot as prices surge.

Inventories are dropping in the Oklahoma town as global demand outpaces supply. According to U.S. government data, they have fallen to about 30.5 million barrels, and traders are heavily betting they will drop further next week, and perhaps throughout the rest of the month. For its part, OPEC+ is ignoring an over-heated oil market and releasing extra production too little and too slowly. The cartel agreed on Wednesday to a nominal increase of 400,000 barrels a day. But as the tank farm balances in Cushing say now, the market needs more — and soon.

At the current estimate of 30.5 million barrels, the buzzword in the market now is “tank bottoms.” For operational reasons, tanks always need to have some oil in them so they are never fully empty. So, traders talk about tank bottoms when Cushing inventories drop toward the 20-to-25 million barrel range. The last time Cushing stocks dropped below 25 million — in mid-2018 — oil prices made a push toward $100 a barrel.

The amount of oil in Cushing would be much lower if not for the White House’s decision last year to release millions of barrels of crude from the country’s Strategic Petroleum Reserve. Since October, the U.S. government has added about 27 million barrels to the market, slowing the drawdown in Oklahoma somewhat. With Cushing inventories under pressure, the Biden Administration may need to tap the SPR again this year.

Not everyone agrees that Cushing is heading to tank bottoms. The refinery maintenance season is around the corner, and that should lower demand for crude in the U.S. In October and November, traders made a similar bet, and the market self-corrected. This time, however, some of the correcting mechanism — like a reduction in U.S. crude oil exports — aren’t working as well.

Zoom out from the microcosm of Cushing, and it’s a similar picture around the world, with oil inventories dropping well below the 2015-2020 range. Despite expectations the oil market would move into a surplus in December, the global economy has continued drawing down its stocks over the last two months. Add to that the fear emanating from the Ukraine crisis of economic sanctions on Russia — the world’s second-largest oil exporter after Saudi Arabia — and it’s easy to see why traders are paying a premium for barrels at hand.

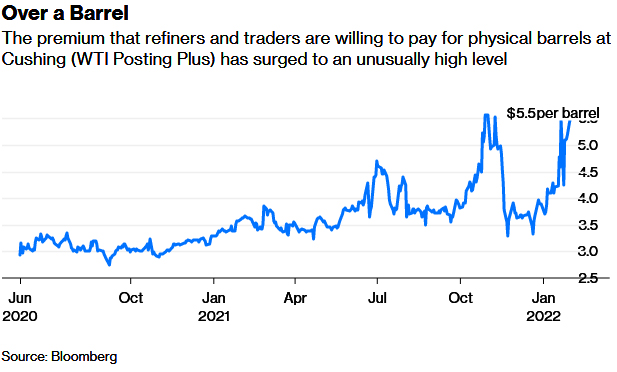

In the oil market, that’s known as “backwardation”: spot prices are higher than forward prices, with the price curve in a downward slope. On Wednesday, the WTI front-month contract traded at a premium of 180 cents per barrel over the second front-month, reflecting a desire to hold barrels right now. That’s an unusually large premium.

But there’s another signal of the scarcity flashing red. In the physical market, where actual barrels of oil are bought and sold, traders track the so-called WTI Posting-Plus differential. The P-Plus, as the arcane metric is known, reflects the premium that refiners and traders are willing to pay to buy barrels at Cushing today. It has zoomed to $5.63 per barrel, an extreme level. Over the last three decades, the WTI Posting-Plus differential has only traded at that range, or higher, on 24 occasions out of 7,544 trading days. That’s a lot of sizzle for the market to handle.

If OPEC+ doesn’t act, whether voluntarily or under pressure from the White House, that obscure indicator could transform into more prosaic and painful figures: sharply rising gasoline prices and, with that, even higher inflation.

Javier Blas is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy and commodities. He previously was commodities editor at the Financial Times and is the coauthor of “The World for Sale: Money, Power, and the Traders Who Barter the Earth’s Resources.” @JavierBlas. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on Februeary 03, 2022. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

energiesnet.com 01 12 2022