By Stephen Wilmot/WSJ

LONDON

EnergiesNet.com 01 31 2022

Electric vehicles won’t get a “100% Made in U.S.A.” stamp for a good while yet.

U.S. auto makers are pouring billions of dollars into domestic EV factories and lithium-ion battery plants to supply them. General Motors this week announced $6.6 billion of EV investments into two Michigan plants, including $1.3 billion from its South Korean battery partner, LG Energy Solution. Ford F 0.46% announced similar projects in Tennessee and Kentucky last September alongside LG’s archrival, SK Innovation. 096770 0.23%

Move further upstream in the U.S. EV supply chain, though, and the torrent of capital turns into a trickle. Unless that changes, the headlong pursuit of EVs in Detroit and California alike risks replacing the American driver’s dependence on Middle Eastern oil with an equally problematic reliance on Chinese battery materials.

Some projects are under way, often led by partnerships or supply deals with car makers. Relative to the scale of investment downstream, though, they seem small.

GM last month announced a joint venture with Posco Chemical, another South Korean company, to open a cathode materials plant in the U.S. in 2024. The cathode is the most valuable component of a battery cell, accounting for about 40% of its cost. The car maker said the factory would employ hundreds of people.

At the start of the supply chain, a clutch of miners are developing U.S. prospects for battery materials such as lithium and nickel. Toronto-listed Talon Metals, which owns the Tamarack nickel project in Minnesota alongside iron-ore giant Rio Tinto, last week said it would sell stock worth at least 33.9 million Canadian dollars, or roughly $27 million, to further its plans, exploiting a strong share price after Tesla committed to purchase at least 75,000 metric tons of Tamarack nickel over six years.

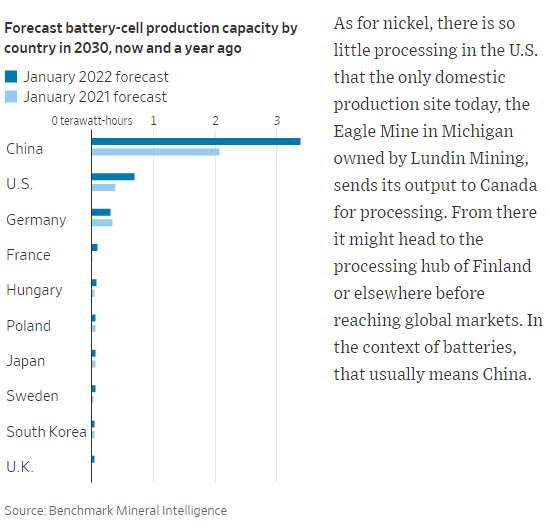

Yet it is the obscure intermediate links in the supply chain that require most attention. This is where China really dominates the battery industry today.

Chinese lithium miners Ganfeng Lithium and Tianqi Lithium do more work turning the metal they extract into useful chemical compounds than their big U.S. peer, Albemarle. Ganfeng even makes EV batteries itself. In their emphasis on vertical integration, the Chinese players are in some ways clean-energy takes on the likes of Exxon Mobil and Royal Dutch Shell —“integrated oil companies” that pump, refine and market their resources.

Until this kind of situation changes, America’s new battery plants will have to source materials chiefly from China, handing geopolitical leverage to Beijing as the EV industry expands. The need to avoid this outcome is a rare point of bipartisan consensus in Washington.

The infrastructure bill President Biden signed into law in November included $6 billion of funding for the production and recycling of batteries and their raw materials, with priority for companies owned and operated in the U.S.

Recycling might seem a low priority given how few EVs are on the road, but recycling startups are in fact among the more promising American battery-materials suppliers. Redwood Materials, the five-year-old brainchild of Tesla’s longtime chief technology officer, JB Straubel, and its smaller rival Li-Cycle collect waste battery materials—sometimes called “urban mining”—break them down and then reprocess them for sale back into the supply chain. Redwood also plans to turn its recycled materials into cathodes.

The recall of GM’s Bolt model last year was a boon for Li-Cycle, which has a partnership with the car maker. Such problems aside, the recyclers will rely much more on manufacturing scrap than end-of-life EVs for source matter over the coming decade. As much as 40% of raw materials can be lost as battery factories ramp up while trying to meet demanding automotive quality requirements. Even mature plants typically scrap 5% to 10% of their supplies.

A private funding round valued Redwood at $3.7 billion last summer, and it got another $50 million from Ford in September. The sector needs much more investment, but its economics remain unproven. Competing with a much better-established Chinese industry isn’t an obvious proposition for investors, even with subsidies thrown in.

That leaves U.S. car makers tentatively leading even the upstream supply-chain push, in alliance with the Energy Department. The future of EVs is often assumed to depend on solving consumer problems such as slow charging infrastructure and range anxiety. Instead, they could be slowed down more by the conundrum of building the foundations of a battery industry.

Stephen Wilmot at stephen.wilmot@wsj.com

Appeared in the January 29, 2022, print edition as ‘The Real Brake on The EV Revolution.’

wsj.com 01 29 2022