By David Flickling

The world has failed to agree to stop burning fossil fuels. After two weeks of negotiations, a draft decision at the UN climate change conference COP27 in Sharm El Sheikh, Egypt, promised a compensation fund for climate change damage but fell short of a push by the US and Europe for a “phase-down” on oil, gas and coal.

In fact, it’s even worse. Although a coal phase-out was agreed at last year’s Glasgow conference, other fossil fuels will remain immune. Twenty years from now, we will likely still see global climate conferences failing to agree on phasing out (let alone phasing out) fossil fuels. And that’s fine – because what matters isn’t the words in an international agreement, it’s whether our carbon emissions are falling fast enough. The prospects are much brighter on that front.

There’s a simple reason why consensus is so difficult to reach at UN climate conferences. The words released at the end of the COP sessions are not just words, but a quasi-legal text designed to flesh out the binding commitments of the 2015 Paris Agreement. If only one of the 193 parties objects to the conference decision, there is no agreement to announce. That’s why activists, fossil fuel lobbyists, and diplomats fight so hard for each emphasis. The COP decision isn’t exactly law, but it still influences the actions of governments and corporations in the real world.

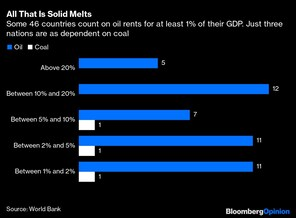

As we lumber along the road to net zero, a significant number of UN members are getting uncomfortable about the destination. The Organization of Petroleum Exporting Countries numbers 13 states, with 11 more in the OPEC+ grouping. Throw in non-OPEC+ countries highly dependent on oil and gas — like Guyana, Qatar, and Turkmenistan — and you have as many as 50 delegations, depending on how you draw the line. For that group, equivalent to a quarter of UN member states, a commitment to phase out petroleum is a vow to shrink their own economies.

The situation with oil and gas is different to the one with coal. Heavy, messy, and expensive to transport, the solid fuel is far harder to trade than petroleum. Only half-a-dozen countries are major exporters. Hardly any count it as central to their economies, the way oil is to scores of nations. That makes it far easier to negotiate reductions.

For decades, the major cleavage in environmental talks has been between rich and poor nations. That division remained stable for so long because on one level economic development is simply a process of using more energy. At a time when fossil fuels were the only viable low-cost energy source around, a promise to reduce emissions was a pledge for poor countries to stay poor.

What has changed is the remarkable rise of renewable technologies that can compete with conventional energy for both cost and environmental reasons. This has shifted the divide in climate talks away from the old divide between rich and poor to a new divide between fossil fuel exporters and importers. The move is best illustrated by last year’s net-zero pledge from India, which for many years has been the flag-bearer of emerging markets, who resisted such commitments until they could get rich. This year’s agreement by wealthy nations on a claims settlement facility to compensate small and poor countries for climate-related disasters is another sign that new diplomatic alliances are emerging. Ditto the ebullience of oil exporters, who resisted any phase-down language.

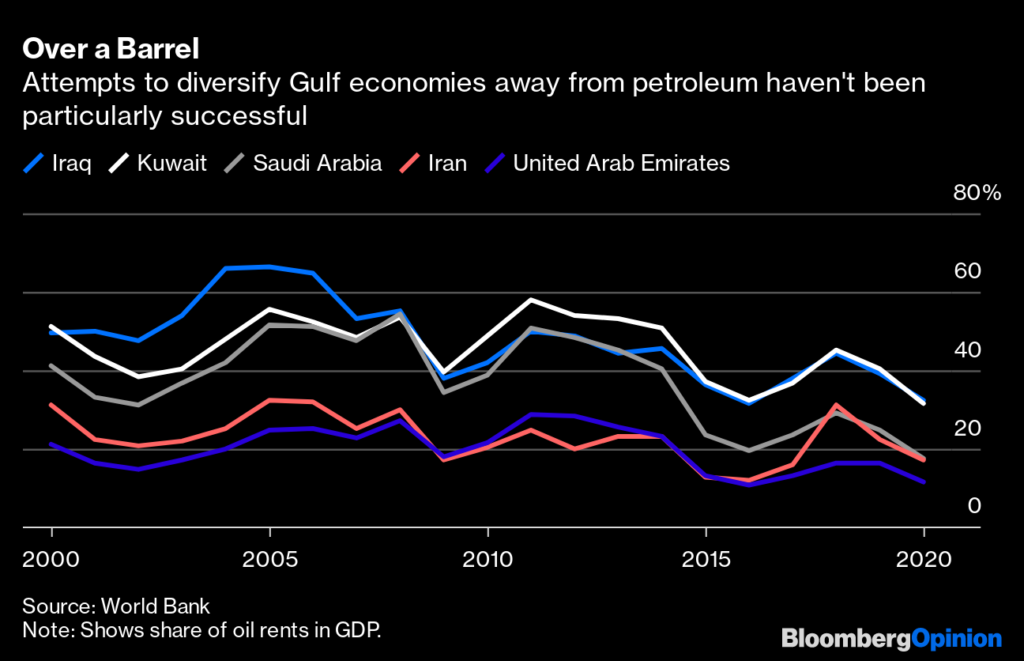

To find out who will win in this battle between importers and exporters, it is worth considering the options available to each group. If you’re a major oil exporter, there’s no viable alternative business out there. Oil made your country rich. (For the likes of Saudi Arabia, it arguably made your country a country.) It’s such a dominant trade that competing industries have withered in its shadow — the Dutch disease phenomenon familiar to many commodity exporters.

The situation is different for importers. What your people want is affordable energy and food, and the fruits of development that they bring. For a century or so, fossil fuels were the only way to do that — but consumers don’t care if their scooter runs on oil or their air conditioner runs on gas, as long as it works and doesn’t cost too much.

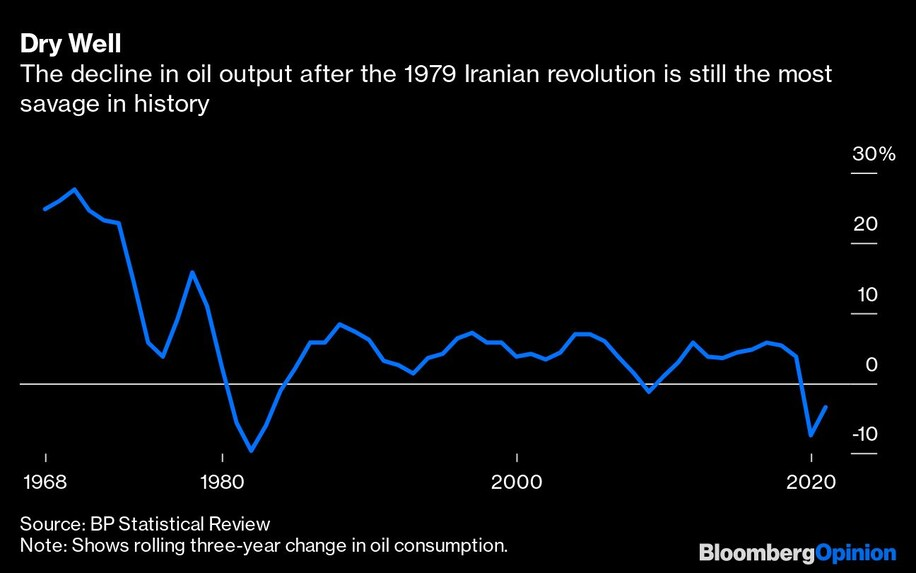

The events of 2022 have accelerated this trend. The last time the world faced an energy crisis like this—in the early 1980s, when the Iranian Revolution and Iran-Iraq War choked off oil supplies while the Federal Reserve’s war on inflation dampened demand— Oil consumption fell 10% from the previous three years to 1982, still the sharpest such decline in history.

What is different now is that there are viable, affordable alternative sources of energy. Renewable energy is the cheapest way to generate new electricity for two-thirds of the world’s population, rather than coal or gas. In major auto markets, new electric vehicles are already costing less to own and operate than their combustion-powered equivalents. Even gas as a raw material for the chemical industry will be undercut by green hydrogen in this decade.

The future that is emerging will profoundly disrupt the countries most dependent on fossil fuel exports – but ultimately consumers and importers will decide which energy sources to lean on. The economy was already relentlessly pushing them toward low-carbon alternatives. The war in Ukraine and Russia’s attempt to weaponize energy exports have added a strong pinch of national security to the mix.

What the world needs is not strictly worded international agreements, but a reduction in carbon emissions. Initiatives like this year’s loss-and-damage facility can certainly cement the alliance between rich and poor fossil fuel importers. The necessary change is already happening far from the conference halls of Sharm El Sheikh – and it will continue, whatever the state of diplomacy.

___________________________________________________

David Fickling is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering commodities, as well as industrial and consumer companies. He has been a reporter for Bloomberg News, Dow Jones, the Wall Street Journal, the Financial Times and the Guardian. Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on November 20, 2022. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

energiesnet 11 21 2022