Bloomberg News

LONDON

EnergiesNet.com 03 04 2022

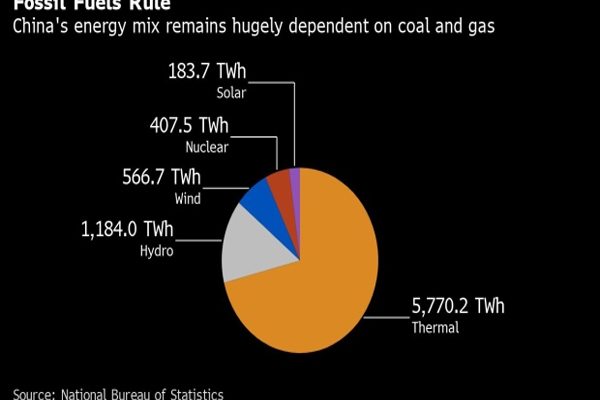

Higher commodity prices are crashing over China’s economy after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, intensifying Beijing’s focus on energy security just as lawmakers gather for their annual policy-setting meeting.

The world’s recovery from the pandemic had already launched commodities prices to new highs and forced China’s government to rethink how it balances short-term energy needs with its long-term aim of delivering a carbon neutral society. Now, the war in Ukraine is putting extra pressure on the world’s biggest importer of oil and gas, and an economy that relies on coal to fuel its industrial base.

It isn’t clear what specific measures could be unveiled at the National People’s Congress, which begins in the capital on Saturday. But China’s energy policies in recent months have been skewed to supporting growth in an economy that has stumbled since the summer. Some of the restraints around energy use and carbon emissions that proved so inflationary last year have been relaxed as Beijing battled a power crunch. That’s shifted much of the emphasis from the steps necessary to transition away from fossil fuels.

The government this week issued orders to prioritize the security of its energy and commodities supply, triggered by concerns over disruptions stemming from the Russian invasion. That sets up the meeting in Beijing as a showcase for the government’s sharpened priorities.

Last year’s “campaign-style” attempts to control energy consumption are unlikely to be repeated in 2022, said Lara Dong, head of power and clean energy research at IHS Markit. Instead, expect more measured policies from the NPC that “balance climate goals, economic growth and supply security,” she said.

China has yet to publish its five-year plans covering the energy and power sectors through 2025, and the NPC could be the venue for their release. In the overarching plan for the economy laid out last year, Beijing established that non-fossil fuels should rise to 20% of the energy mix by 2025, and that energy intensity, as measured by consumption per unit of GDP, should fall by 13.5%, and carbon intensity by 18%.

In comments this week reported by the official Xinhua News Agency, Vice Premier Han Zheng said China should focus more on carbon intensity rather than overall energy consumption as its chief means of cutting emissions. That shift would take the pressure off the economy as a whole and put the onus on individual industries to become more carbon efficient. It could also suggest that China’s carbon market, launched in July, will have a bigger role to play in meeting the nation’s climate goals.

Lower Growth

The biggest headline at the Congress may well be a lower target for economic growth. That would help ease pressure on energy supplies. But lower growth in China is still breakneck by the standards of many other countries, which means digging up ever more dirty coal while at the same time launching major new clean energy projects.

The world’s biggest buyer of raw materials was forced to contend with spikes in commodities prices in the summer, caused by its post-pandemic stimulus, and an unprecedented run-up in coal prices during the energy crisis in the fall. As energy markets soar once again after the Russian invasion, the government will be keen to avoid policies that compound inflationary pressures or risk repeating last year’s power outages.

The shift was marked by President Xi Jinping’s comments in January that the nation’s climate goals shouldn’t conflict with other priorities, including securing adequate supplies of energy and materials and ensuring “the normal life of the masses.”

It’s most evident in the government’s approach to coal mining, which has seen production lifted to record levels and prices subjected to controls to ensure that China’s mainstay fuel remains plentiful and affordable. The steel industry has also been given a pass. Its deadline to peak its emissions was extended by five years to 2030, as Beijing prepares the ground for stimulus measures to boost the economy.

And the state planning agency has said that local governments will be given more leeway in setting energy conservation goals. The rush to meet targets last year contributed to the energy crisis as rationing on the heaviest users and carbon emitters constrained output of key materials.

What Bloomberg’s Economists Say…

Electricity shortages last year hit China’s growth hard. Factories were forced to curb output. We see the government signaling a more flexible energy policy than in 2021, when tight production controls on energy intensive sectors weighed on overall growth.

— Chang Shu, David Qu and Eric Zhu

See here for full note

But China’s continued embrace of coal in particular could put pressure on the government to show it isn’t backsliding on Xi’s longer term climate commitments. Researchers have pointed to the alarming pace at which new coal-fired power plants are being added, and last month the state planning agency approved investment in three billion-dollar coal mines as it seeks to avoid a repeat of the power shortages that wracked the economy in the autumn.

As a result, the NPC could throw up a lot of promises on clean energy, designed to show that coal’s grip on the economy won’t last for ever, and that Xi’s signature pledge to peak national emissions by 2030 will be met.

Last year’s highlight was a big push on nuclear power. This year could include more details on the plan to establish massive renewable energy hubs in the interior, as well as the investments in the electricity grid that are needed to transmit that power to eastern population centers. Emerging clean energy sources like hydrogen could also get a shout-out.

The war in Ukraine will surely intensify China’s anxieties around imported fossil fuels. That can only favor renewable power in the long term — a substitute that doesn’t spoil the atmosphere and isn’t dependent on foreign suppliers.

bloomberg.com 03 03 2022