‘Dubai-like prices’ threaten to contribute to migration trend. Government spending has risen after years of fiscal tightening

Fabiola Zerpa, Ezra Fieser and Andreina Itriago Acosta, Bloomberg News

CARACAS

EnetgiesNet.com 11 02 2022

Inflation is roaring back in Venezuela, threatening to undermine the fragile economic recovery orchestrated by President Nicolas Maduro and rekindle a migration wave that had just begun to ease.

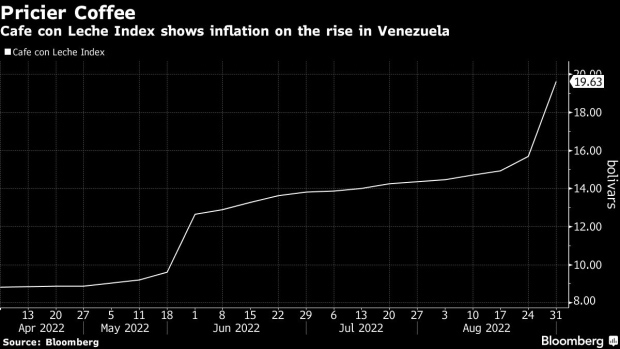

Prices have soared at an annual rate of 359% over the past three months, according to an index compiled by Bloomberg. While that’s well down from the wildest hyperinflationary highs of recent years — the index clocked in around 300,000% back in 2019 — it’s up markedly from earlier this year.

The spike in prices reveals an important policy shift by Maduro. After years of reining in spending and cutting a bloated budget deficit, the government is loosening the purse strings again, shelling out cash for everything from holiday bonuses to handouts for Socialist party loyalists. All that additional cash in the economy is fueling declines in the bolivar’s value against the dollar and driving consumer prices higher.

“Venezuela has technically exited from hyperinflation, but it’s locked in high monthly inflation rates,” said Daniel Cadenas, an economics professor at the Metropolitan University in Caracas. “We won’t see less than 100% annualized inflation unless there is a change in economic policy.”

The pain of diminishing purchasing power is one of the reasons people are being forced to migrate, Cadenas said. More than 7 million have already left the country in recent years, according to estimates by the United Nations, with tens of thousands turning up at the US border this year.

“Venezuela has Dubai-like prices for products while people are paid Sudan-like salaries. This affects mostly the poor, 93% or the population,” Cadenas said.

By allowing the US dollar to circulate freely, the Maduro administration spurred an increase in consumer spending, which, coupled with a modest increase of oil production, is driving a surprising economic rebound. Gross domestic product is expected to expand 6% this year, according to the International Monetary Fund. While that would be the biggest expansion in 15 years, the economy remains a shadow of its former self.

Maduro has promoted the recovery as an unlikely comeback for a country that is sanctioned by the US. “A persecuted, tortured, sanctioned, blockaded country has found a path by using its own engines to activate the real economy,” he said last week.

Venezuela emerged from hyperinflation in January following a central bank decision to increase dollar supply in the official exchange market. The strategy yielded some results at the beginning of the year, with monthly inflation moderating in March.

But price increases have accelerated recently. The central bank reported consumer prices rose in August — the most recent data available — while the opposition’s Finance Observatory said annual inflation is running near 157%. Bloomberg’s Cafe con Leche index — based on the price of a cup of coffee in Caracas — puts the figure at 158% in the past year.

Some economists had forecast annual inflation below 100% in 2022.

Weaker Currency

The bolivar has weakened by a third in the last three months, to around 9 bolivars per dollar. An easing of public spending restrictions has led to a “significant” increase in the supply of local currency, which is boosting demand for US dollars, Cadenas said.

Tamara Herrera, director of financial analysis firm Sintesis Financiera, said the trend is likely to get worse as the government makes further year-end payments to public employees, which will boost the demand for bolivars ahead of the Christmas shopping spree.

Government spending rose to 18% of gross domestic product this year, compared to around 12% in 2021, Herrera estimates. She forecasts it will rise further to 21% of GDP next year.

The pain of higher prices and the effect of years of migration is being felt at the Chacao market in eastern Caracas, a comparatively wealthy enclave of the capital. Vendors there are struggling to keep up.

Numerous clients at Sonia Benavides’s coffee shop have left the country. Those that remain are buying only what they need.

The 67-year-old Benavides is considering using cheaper, lower-quality products to keep her prices low. She’s already nearly doubled what she charges for a large latte in the past three months to $1.95. “It’s either good quality or good price, it’s impossible to have both,” she said.

–With assistance from Nicolle Yapur.

bloomberg.com 11 01 2022