The US’s New Approach to Venezuela Is Starting to Bear Fruit

Ezra Fieser and Nicolle Yapur, Bloomberg News

BOGOTA/CARACAS

EnergiesNet.com 12 09 2022

On a Saturday morning in late November, a top deputy to Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro and a leader of a group of opposition parties met at a hotel in Mexico City to announce they’d reached a deal to unlock billions of dollars in frozen funds to rebuild the country’s crumbling infrastructure. The breakthrough agreement between bitter rivals was promptly blessed by the administration of President Joe Biden, which eased some sanctions hours later, allowing US driller Chevron Corp. to pump more oil in the country.

It was the most tangible evidence yet that Washington and its allies in Venezuela have changed course when it comes to Maduro, an authoritarian leader so despised only a few years ago that the Trump administration put a $15 million reward out for his arrest and slapped sanctions on his administration.

After years of failed US attempts at fostering regime change, Biden envoys began talks with the Maduro government in March, shortly after Washington banned Russian energy imports in response to President Vladimir Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. The dialogue paved the way for a prisoner exchange in October. The US also demanded that Maduro restart negotiations with the opposition as a condition for any future concessions.

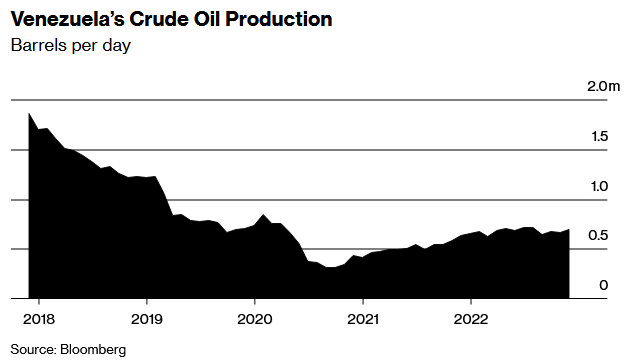

The rapprochement is driven, in part, by the Biden administration’s desire to do whatever it can to smooth out oil market disruptions that have sent prices soaring. Although years of government mismanagement has decimated Venezuela’s petroleum industry—oil production now averages about 690,000 barrels a day, compared with more than 2 million a day in 2017—the country still sits atop the world’s largest reserves.

The overtures to Caracas are also a tacit acknowledgment of the failure of the policy under President Donald Trump to push out Maduro by supporting opposition leader Juan Guaidó. “Global energy prices are one of several factors driving US policy toward Venezuela, but the recent engagement also stems from a desire to break the diplomatic stalemate around Guaidó,” says Eurasia Group analyst Risa Grais-Targow.

No one expects California-based Chevron to return the country to its past glory as an oil powerhouse or meaningfully ease the global energy crunch. One of the last international companies to stick it out after 2019, when the US blocked transactions with state oil company Petróleos de Venezuela SA, Chevron had effectively stopped pumping oil in Venezuela. Within a year, it may be able to ramp up output to about 200,000 barrels a day in the four joint ventures it operates with PDVSA. The additional production won’t offset the disruption caused by sanctions on Russia, which exports as much as 3 million barrels a day.

The bigger winner is Maduro. Three years ago he was isolated internationally, Venezuela’s economy was in the throes of a seven-year recession, and hyperinflation made its currency worthless. About 7 million people have fled the country during his tenure, and per-capita gross domestic product is less than a quarter of what it was a decade ago, but as the 60-year-old leader nears a decade in power, the worst of the crisis appears to have passed.

Maduro is traveling internationally, including a visit to the recent climate summit in Egypt, where he wrangled a handshake with US envoy John Kerry and exchanged pleasantries with French President Emmanuel Macron. Newly elected left-of-center governments in Latin America are restoring relations with his government. At home, Caracas streets once packed with protesters demanding he step down are filling with new restaurants and advertisements for concerts and upscale stores.

The recession is over, thanks mainly to the government’s decision in 2019 to allow the US dollar to circulate alongside the bolívar. GDP is forecast to expand 7.6% this year, according to a Bloomberg survey of economists, and 3.9% in 2023.

Negotiating with the US helps Maduro improve his standing on the global stage, says Luis Vicente León, director of Caracas consultants Datanalisis. “It opens doors to reestablish some form of a relationship with the US,” he says. “It could also result in political agreements that allow Maduro to generate some political flexibility that helps him to consolidate a more recognized government in the future.”

Biden still doesn’t consider Maduro to be Venezuela’s rightful leader because the 2018 presidential election was marred by fraud, continuing his predecessor’s policy of recognizing Guaidó, the 39-year-old head of the opposition-led National Assembly. But Guaidó’s standing is falling both at home and abroad. Governments around the world and the European Union have ceased to recognize him, and some of Venezuela’s opposition parties are threatening to withdraw support from his so-called interim government next month. “Now, Biden can adjust the Venezuela foreign policy that Trump designed—which failed—to a more realistic policy that uses sanctions as incentives to negotiate and not as permanent punishment,” says Michael Penfold, professor at the Institute of Advanced Studies in Administration in Caracas.

Biden officials have said they will further ease sanctions if Maduro continues to make agreements with the opposition in Mexico City. The talks, which restarted last month, were stalled since October 2021 when Maduro walked away. Several previous rounds of negotiations failed to produce any meaningful breakthroughs. This time the opposition and the US are pushing Maduro to set a date for free and fair presidential elections in 2024, to allow some barred politicians to run and to invite foreign electoral observers to monitor the vote.

Stalin González, a member of the opposition delegation, says that by negotiating in Mexico, Maduro has a channel to pursue concessions from the US, including sanctions relief. “The international community is willing, as it has always said, to give these incentives if the demands of the Venezuelan people are met,” he says.

The infrastructure plan, which uses $3 billion in funds frozen in foreign bank accounts, is a first step, González says. A few days after he signed it, Maduro held a rare news conference to hail the agreement, saying it would be used to fix 2,300 schools, repair parts of the electricity grid and buy vaccines and medications. At the same time, he cast doubt over the future of the talks by appearing to link electoral conditions to the lifting of US sanctions. “Is it free elections that you want? Fair and transparent?” he said. “Take them all away.”

—With Patricia Laya

Read next: A Nation in the Crosshairs of Climate Change Is Ready to Get Rich on Oil

bloomberg.com 12 08 2022