Manuela Andreoni, NYTimes

RIO

EnergiesNet.com 11 01 2022

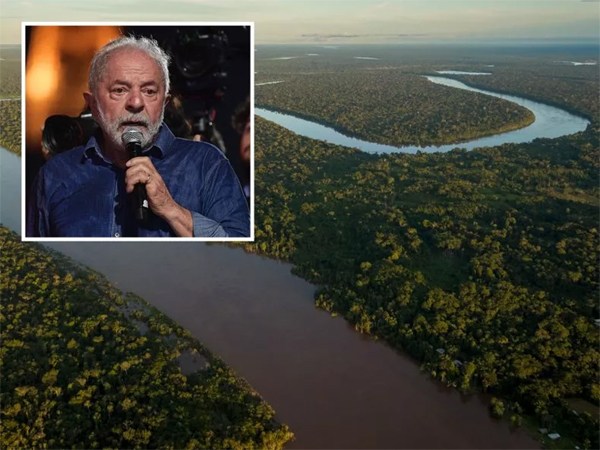

In the closest election since the Brazil’s return to democracy in 1985, voters decided to bring back former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, who made climate a cornerstone of his campaign, and rejected the incumbent, Jair Bolsonaro, whose presidency saw a sharp increase in deforestation.

“Brazil is ready to resume its leading role in the fight against the climate crisis,” Mr. da Silva told supporters in his victory speech on Sunday. “We will prove once again that it’s possible to generate wealth without destroying the environment.”

The pledge matters because Brazil contains much of the Amazon rainforest. Right now, the forest absorbs planet-warming carbon dioxide from the atmosphere and stores it in tree roots, branches and the soil. By one estimate, there are 150 to 200 billion metric tons of carbon locked away in the forest. But that could change. If deforestation continues, the jungle may soon become a net emitter of greenhouse gases.

The region is also one of the world’s most biodiverse places on Earth, and protecting it is key to fending off a global biodiversity crisis.

At home: back to fighting deforestation

When Mr. da Silva first took office in 2003, deforestation rates were more than twice what they are today. He enacted policies that reduced them by 80 percent. The lowest pace of deforestation was recorded two years after he stepped down in 2010.

When Mr. Bolsonaro assumed office in 2019, he slashed funding for environmental protection agencies, made environmental fines easier to ignore and encouraged his supporters to continue mining illegally. Deforestation rates started to shoot up again. Brazil lost over 12,000 square miles of the Amazon jungle from 2019 to 2021.

Now, Mr. da Silva says he plans to resume the policies that reduced forest loss.

“Now, we will fight for zero deforestation in the Amazon,” he said. “Brazil and the planet need a living Amazon.”

But defiance against policies to protect the forest will likely be strong among Mr. Bolsonaro’s supporters both in Congress and in the Amazon. He won in more than half of the states that make up the forest.

Mr. Bolsonaro has long championed the logging, mining and cattle industries. While destructive to the forest, these industries, which often operate illegally, also provide some of the very few economic opportunities in the region.

Abroad: a focus on the global south

Mr. da Silva’s two terms as president, from 2003 to 2010, were marked by efforts to overhaul global governance bodies like the United Nations Security Council and to raise the profile of developing countries in world affairs.

There are signs that he could make those efforts a priority again, this time with special focus on climate issues.

He may “mobilize other countries in the global south to defend that any reform to global governance takes climate seriously, but also has input from developing countries,” said Adriana Abdenur, who directs Plataforma Cipó, a research organization in Brazil that focuses on climate policy.

Months before the election, Mr. da Silva’s advisers were already coordinating with Indonesia and the Democratic Republic of Congo to help pressure wealthy nations for more financing to protect forests. Marina Silva, his former minister of environment, told Reuters on Monday that Mr. da Silva would send a representative to COP27, the global climate summit that starts on Sunday in Egypt. A spokesman for Mr. da Silva said the matter was still being decided.

Mr. da Silva’s main adviser on foreign affairs, Celso Amorim, said the president-elect also planned to invite regional leaders to an Amazon forest summit in 2023. It’s a sign he plans to strengthen the Amazon Cooperation Treaty Organization, which could help countries in the region band together to design strategies to protect the forest and attract foreign investment for sustainable developing projects.

When Mr. da Silva was president, Brazil created one of the most important mechanisms for climate cooperation in forest management, the Amazon Fund. From 2009 to 2019, Norway and Germany donated over $1.2 billion to the fund, which became one of the most important financing mechanisms for environmental protection agencies in Brazil.

Mr. Bolsonaro disbanded the fund’s governing body, which froze all of its operations, even as his government struggled to fight environmental crimes. On Sunday, Norway’s minister of climate and environment told reporters that he would get in touch with Mr. da Silva to resume cooperation between the two countries.

Mr. da Silva is scheduled to take office on Jan. 1.

Manuela Andreoni is a writer for the Climate Forward newsletter, currently based in Brazil. She was previously a fellow at the Rainforest Investigations Network, where she examined the forces that drive deforestation in the Amazon. @manuelaandreoni

A version of this article appears on the New York times (NYTimes) in print on Nov. 1, 2022, Section A, Page 9 of the New York edition with the headline: What Brazil’s Election Means for Climate