By Eduardo Porter

As Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva left Washington in February, closing only his second trip abroad since assuming the Brazilian presidency the month before, his countryfolk couldn’t hide their disappointment with the lackluster US support for their president’s most critical priority: $50 million to help stop deforestation in the Amazon. The amount was so small, noted the Brazilian press, that “it was not cited in the joint statement” of Lula’s visit to the White House.

Apparently all it took was some chummery with President Xi Jinping in Beijing, with a side of Russia’s Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov in Brasilia, to focus Washington’s mind on the Brazilian’s wishlist. Following a trip to China in which Lula said Washington and Kiev shared responsibility for the war in Ukraine, complained about the dollar’s dominance and gushed over the prospect of doing more business with Beijing, the Biden administration responded on Thursday with an offer of $500 million for the Amazon Fund, set up by Lula in 2008 during his second term in office to draw international support for his environmental agenda.

Only Norway, which has oodles of petrodollars to finance environmental efforts around the world, has given more. Brazil “is grateful for the trust and the American contribution to the fund,” the Brazilian Presidency said in a statement to Bloomberg News. It has much to be thankful for. It didn’t just land a promise of cash. It figured out a killer strategy to build support for Brazil’s development: Just exploit Washington’s boundless fear of Beijing.

Irked as it might be by Lula’s diss of the dollar or the red carpet rolled out for Lavrov in the Brazilian capital, the Biden administration is right to play nice and accommodate Lula’s strategy. Brazil is a potentially vital partner that could help address the many crises popping up across the hemisphere, from Venezuela and Haiti to the river of migrants fleeing various other national dumpster fires throughout the region.

Moreover, the competition with China is for real. Over two decades in which the US set off to war in the Middle East, pivoted to Asia and re-pivoted to help fight another war in Europe, China became South America’s biggest trading partner and prominent financier. If the US is to maintain its influence, it must invest more resources and attention in its neighborhood. Brazil is not a bad place to start.

But just as it would be a mistake for the Biden administration to let Lula’s musings about reconfiguring world power around the BRICS hang like a cloud over the relationship, Lula should also take care not to overplay his hand. China’s embrace could easily get too tight for comfort.

Several Brazilian commentators have made the case that Lula’s domestic priorities are way more urgent than any foreign policy agenda. He needs economic growth now to shore up dwindling voter support. He must do what he can to seem friendly to Brazil’s agribusiness interests, which are mostly staunch supporters of his right-wing rival, former president Jair Bolsonaro.

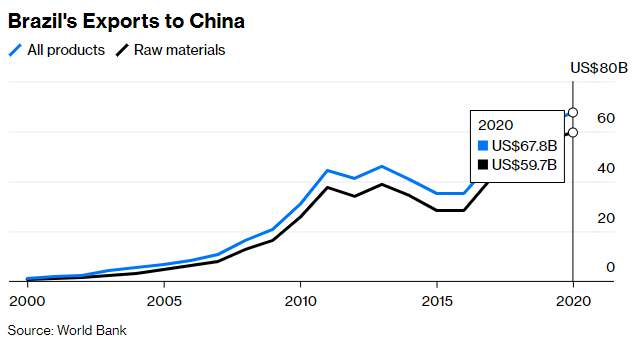

China, Brazil’s biggest export market, to which it sold $60 billion worth of soy, beef and other raw materials in 2020, can help deliver with both. Lula’s visit yielded 15 business deals from semiconductors to energy, worth some $10 billion. China’s BYD is negotiating to buy a Brazilian factory idled by Ford, which left Brazil in 2021, in order to make electric cars there.

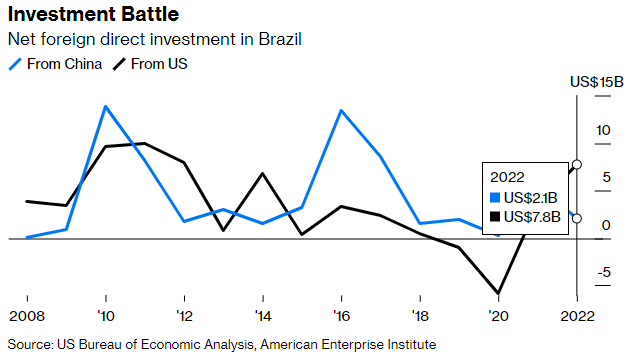

After noting with regret the departure of American firms, Fernando Haddad, Brazil’s finance minister, said Lula’s visit to China amounted to “a new challenge for Brazil: bringing direct investments from China” to underpin “a policy of reindustrialization.” US multinationals had failed to deliver economic development. Time to give Chinese multinationals a chance.

There is some peril to Brazil’s new approach, however, starting with the country’s less-than-stellar track record with industrial policy, which saddled it with a set of protected, uncompetitive behemoths.

Moreover, Brazil’s own recent history is at odds with the notion of China as a motor for anybody else’s industrial development. China’s forays around the world over the last quarter century have focused on procuring the raw materials with which to build an industrial powerhouse at home. Brazil’s experience has been no exception.

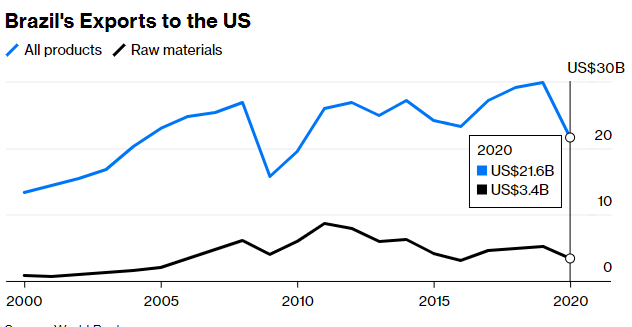

Consider China and Brazil’s booming bilateral trade. Brazil may have exported $68 billion worth of stuff to China in 2020. $60 billion of that was raw materials.

The US, by contrast, bought less. But of the $22 billion total, raw materials accounted for only $3.5 billion.

Investment presents a similar picture. Of the $66 billion in Chinese investments in Brazil recorded between 2008 and 2022 by the American Enterprise Institute’s China Global Investment Tracker, little was spent in developing Brazil’s manufacturing base. Some 75% were in energy projects.

Back in 2011, Jorge Arbache, an economist at the University of Brasilia and advisor to Brazil’s national development bank, argued in an essay that Brazil’s booming yet asymmetric partnership with China reminded him of the Sirens’ song in Homer’s Odyssey: irresistibly seductive but very risky. It “benefits Brazil in the short term but encourages a growing Brazilian dependency of the Chinese economy in the long term,” he said.

In a report published last year, Vinicius Mariano de Carvalho of King’s College in London and Tatiana Rosito, now Secretary for International Affairs at Brazil’s Ministry of Finance, noted that “Brazil has not been able to satisfactorily implement its declared official priorities in relations with China: diversification and increasing the share of high value-added products in Brazil’s exports.”

Lula might wish to look at the performance of Brazil’s industrial economy since China started to ramp up its imports of Brazilian commodities. Because Brazilian imports of Chinese industrialized products boomed, too. Today industrial jobs account for 20% of Brazilian employment, down from 23% 15 years ago. Value-added from industry has declined to 18.9% of gross domestic product, from 23.1% when Lula first came into office. In China, for comparison, industry absorbs 27% of jobs and its value-added amounts to 39.4% of GDP.

In their essay, Mariano de Carvalho and Rosito observe that “this paper does not consider China as a solution to or the culprit of any Brazilian development challenge, but it does regard the Asian power as offering new opportunities (and risks) that are not being fully explored.” A thoughtful, patient China strategy might help Brazil insert itself into high-value productive chains in a new low-carbon economy.

Lula clearly has high hopes. But Beijing — which faces a crop of economic challenges of its own — may not want to share much of its industrial bounty. Indeed, its track record of caring for the wellbeing of the places in which it invests is not very good. While it may make sense for Brazil to leverage Uncle Sam’s fear of a growing Chinese footprint in the neighborhood, it may not want China to move in for good.

__________________________________________

Eduardo Porter is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering Latin America, US economic policy and immigration. He is the author of “American Poison: How Racial Hostility Destroyed Our Promise” and “The Price of Everything: Finding Method in the Madness of What Things Cost.” Energiesnet.com does not necessarily share these views.

Editor’s Note: This article was originally published by Bloomberg Opinion, on April 24, 2023. All comments posted and published on EnergiesNet.com, do not reflect either for or against the opinion expressed in the comment as an endorsement of EnergiesNet.com or Petroleumworld.

Use Notice: This site contains copyrighted material the use of which has not always been specifically authorized by the copyright owner. We are making such material available in our efforts to advance understanding of issues of environmental and humanitarian significance. We believe this constitutes a ‘fair use’ of any such copyrighted material as provided for in section 107 of the US Copyright Law. In accordance with Title 17 U.S.C. Section 107. For more information go to: http://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/17/107.shtml.

energiesnet.com 04 25 2022